13 Punk (as Fuck) Writers You Should Know

Leather Jackets and Leather-Bound Journals

Punk is like any other kind of art—or, more famously, porn—there’s a wide swath of nuances and a lot of gray area, but typically, you know it when you see it. Sure, punk can mean ripped clothes and spiked-out hair and a general disregard for love and property, but more precisely, in my opinion, it means an anti-establishment mentality, a boundary-pushing aesthetic, and a generally non-conformist way of being. The idea of punk has infiltrated almost every kind of art, in one way or another, but here at Literary Hub, we like to read. So, just for fun, and because it’s Jim Carroll’s birthday, I present an incomplete compendium of punk (according to me) writers, whose books are worth your time.

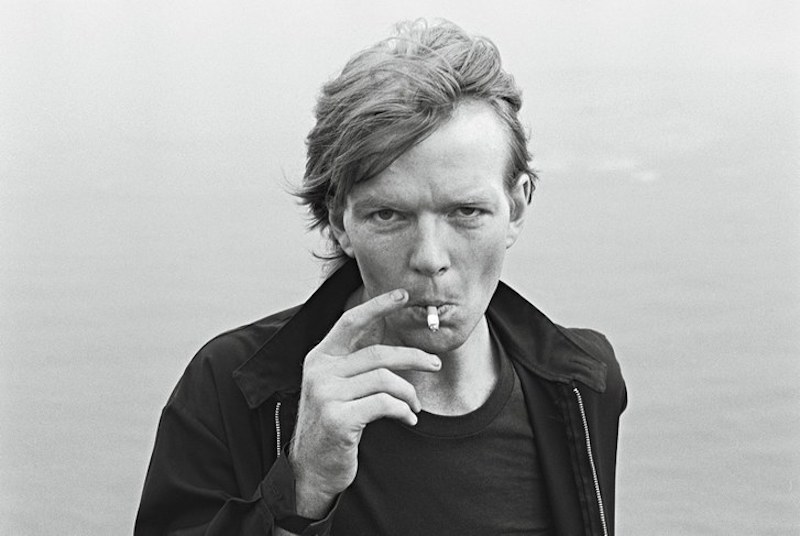

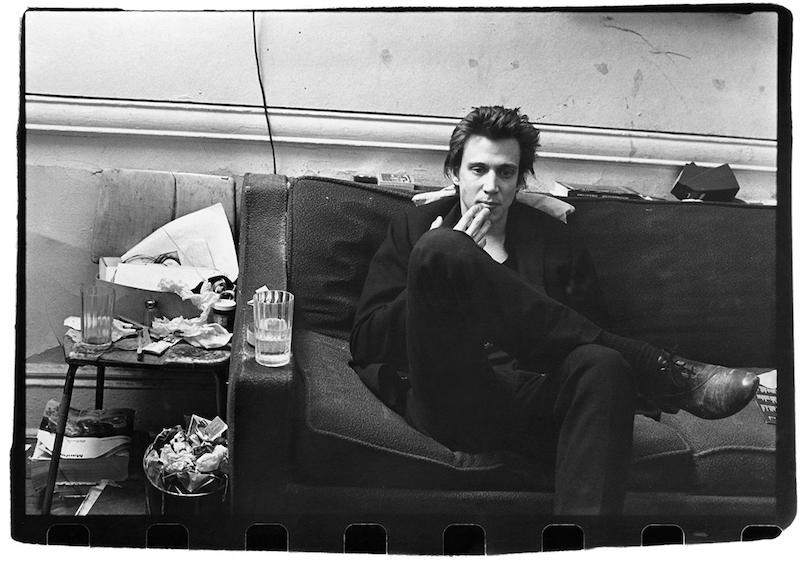

Jim Carroll

Jim Carroll

Today would have been writer, poet, and punk rocker Jim Carroll’s sixty-ninth birthday. First of all, nice. Second of all, Carroll is more or less the reason for this list: he managed to record what some have called “the last great punk album” and also written a blistering memoir of his youth in New York City, which some have called a “cult-classic”—though I think it sort of makes the jump into straight everyday classic when there’s a movie based on it starring Leonardo DiCaprio. Either way, he’s the prototypical punk writer, with both cred and quality in every arena.

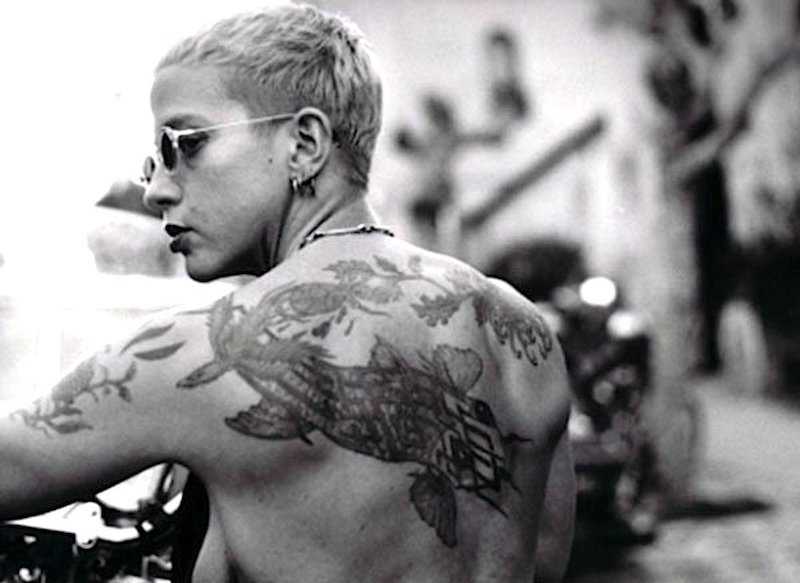

Kathy Acker

Kathy Acker

We all knew that the next writer on this list would be Kathy Acker, didn’t we? Kathy Acker is the most punk of all the punk writers. Or post-punk, if you’re choosy. Her Blood and Guts in High School is a furious metafictional collage, full of disruptions, insertions, and bad language. All of her work is, in one way or another, about breaking boundaries. Plus, I mean, Empire of the Senseless is dedicated to her tattooist. Which I, admittedly a layman, find to be very punk.

Frank Stefanko

Frank Stefanko

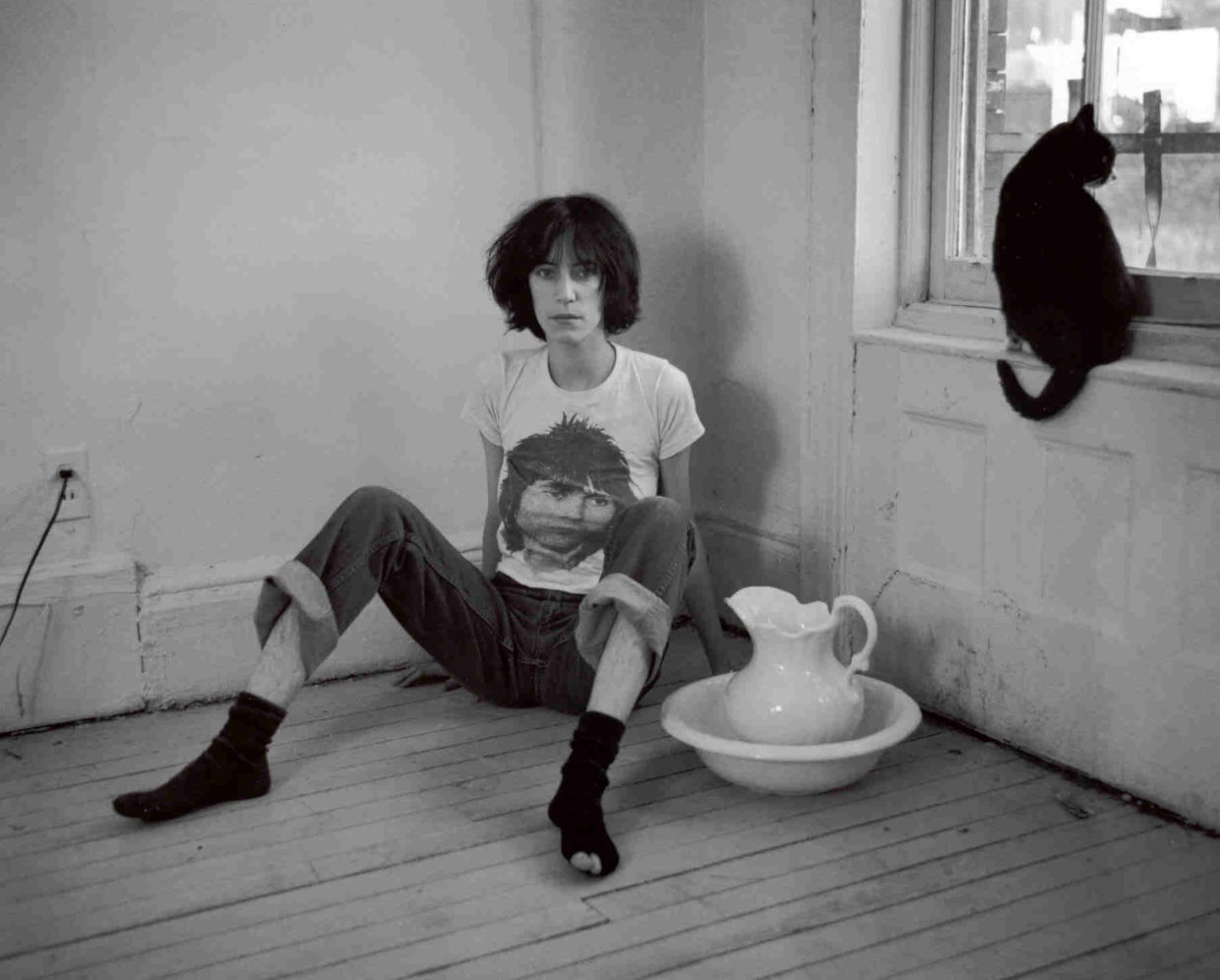

Patti Smith

Patti Smith will tell you that she is not, and has never been, a punk rocker. The thing is, no one believes her. Or maybe they do, but it doesn’t matter, because the actual music is no longer the point, if it ever was. She has long been an icon of art rock, proto-punk, counter-culture, and coolness. In recent years, she has also become a beloved literary voice. (Everyone lost their shit over Just Kids, and rightly so, but if you want the real tea, read the poems.)

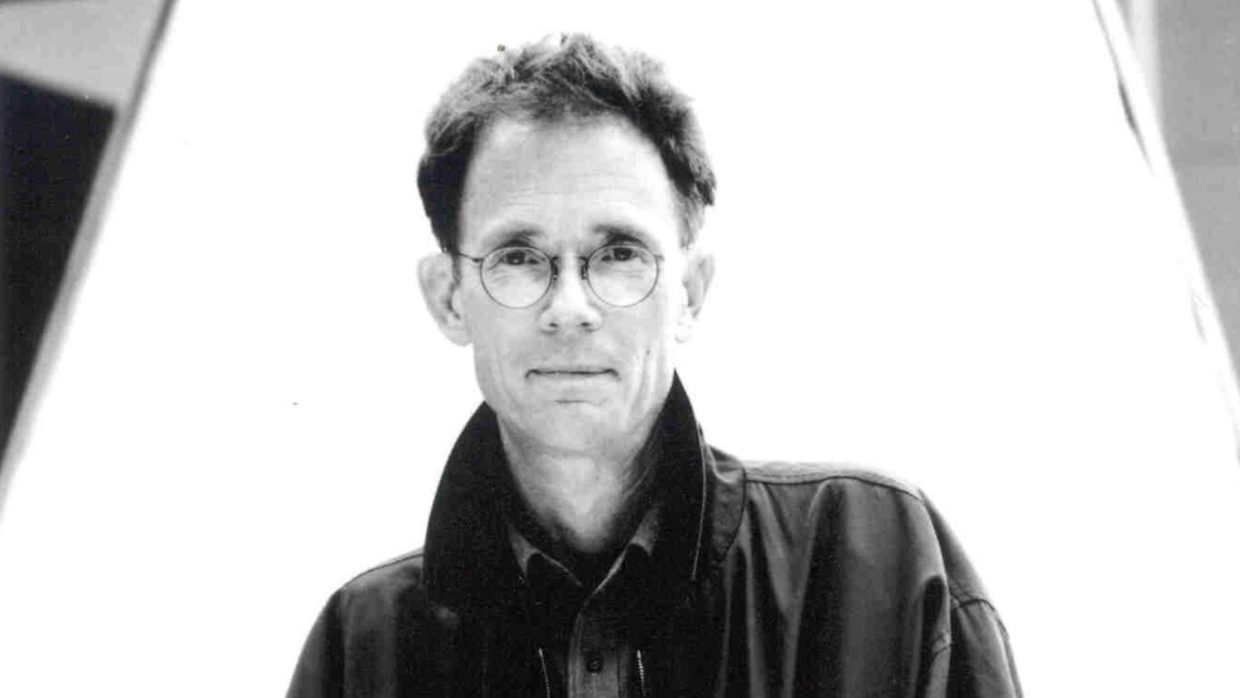

William Gibson

William Gibson

Certainly, as the father of cyberpunk, otherwise known as A Kind of Punk, Gibson deserves a spot on this list. But he also cites punk itself as the thing that made him a writer:

In 1977, facing first-time parenthood and an absolute lack of enthusiasm for anything like “career,” I found myself dusting off my twelve-year-old’s interest in science fiction. Simultaneously, weird noises were being heard from New York and London. I took Punk to be the detonation of some slow-fused projectile buried deep in society’s flank a decade earlier, and I took it to be, somehow, a sign. And I began, then, to write.

And have been, ever since.

Michael Moorcock

Michael Moorcock

Aside from working with Hawkwind and Blue Öyster Cult, Moorcock is a science fiction and fantasy author whom you may not have heard of but who has had major influence in the state of contemporary speculative fiction, and who also, in 1978, had the absolute gall to write a blistering takedown of J.R.R. Tolkien—comparing The Lord of the Rings to Winnie-the-Pooh—entitled “Epic Pooh.” Yes, pun intended. Whether you are a Tolkien fan or not, it is guaranteed to make you chortle.

Lucie Brock-Broido

Lucie Brock-Broido

I could make an argument for her weird, hypnotic, otherworldly poetry, or the random kitten art on her website, but let’s just be honest here: nothing has ever been more punk than Lucie Brock-Broido’s hair.

Katherine Dunn

Katherine Dunn

During her life, Dunn was a highly regarded boxing writer, and took up the sport herself in her 40s. She also wrote the text for Death Scenes: A Homicide Detective’s Scrapbook. She also has one of the strangest minds I’ve ever encountered in literature, as evidenced by her psychotic, incredible novel Geek Love, with its megalomaniacal freaks, science experiment-cum-children, and heavy questions about the nature of humanity.

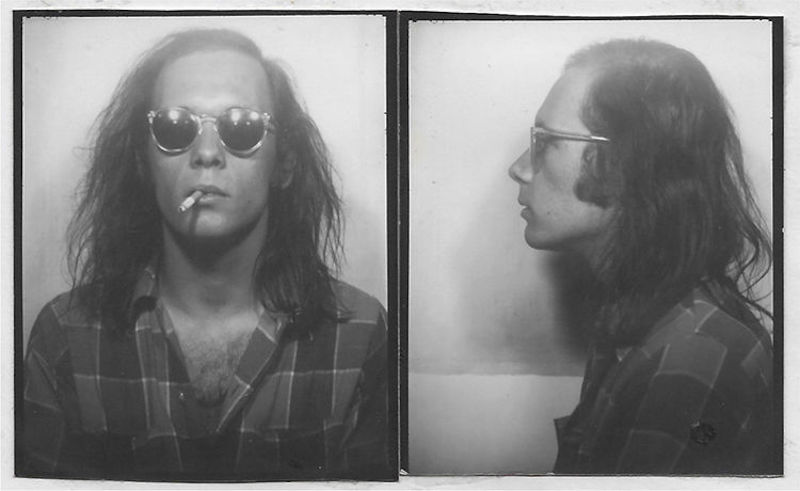

Richard Hell

Richard Hell

I imagine I don’t need to repeat his punk bona fides here, but did you know that Richard Hell was also a writer? He’s published novels, memoirs, books of poetry, and collections of other nonfiction. Even journals. More importantly: a lot of it is pretty damn good, which is not always the case for musicians-turned-writers.

Lynda Barry

Lynda Barry

I think of Barry as a hippie-punk: her edges are soft, her colors earthy, but her work is wild and unbordered and totally disruptive. She represents the best of the DIY zine aesthetic, and she does it with a bright originality that is entirely her own. Plus, comics are inherently punk. I don’t know why. I didn’t make the rules.

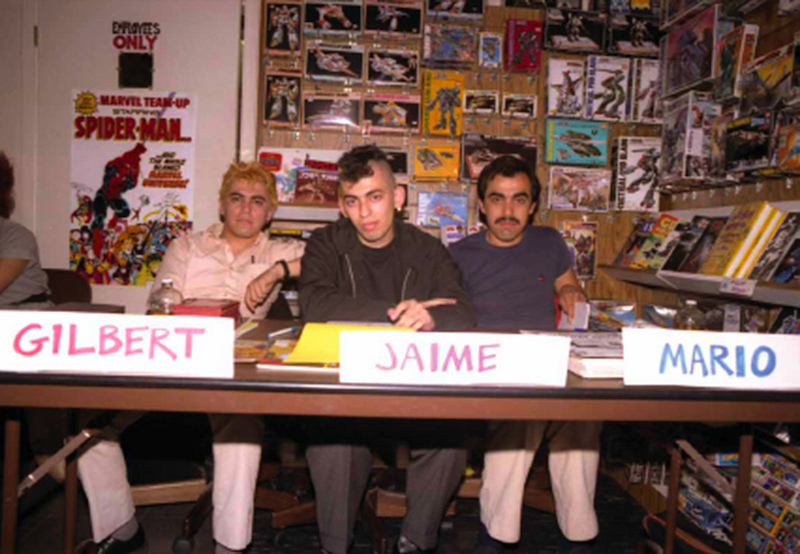

Los Bros Hernandez

Los Bros Hernandez

Speaking of comics: it’s hard to talk about literary punks without mentioning Love and Rockets, which was on the cutting edge of L.A. punk literature in the 80s. “We had our version of punk here,” Jamie told The Guardian, “which came later than London and New York. People were like ‘Oh you guys are starting punk? Ha-ha, late bloomers,’ but we didn’t care.” With the visual format of comics, some of the appeal was in the aesthetics. “The way these people are dressing is way more interesting than the way superheroes dress,” he said. But more importantly, it was about attitude. Describing Esperanza Leticia “Hopey” Glass, Jamie said: “I really liked her spitfire attitude, her foul mouth, and way she didn’t care about what people thought. That’s why I created my punk girls.”

China Miéville

China Miéville

Steampunk, Salvagepunk, the New Weird. Whatever you want to call him, the genre-bending, boundary-breaking Miéville is pretty punk. I mean, have you seen his skulltopus?

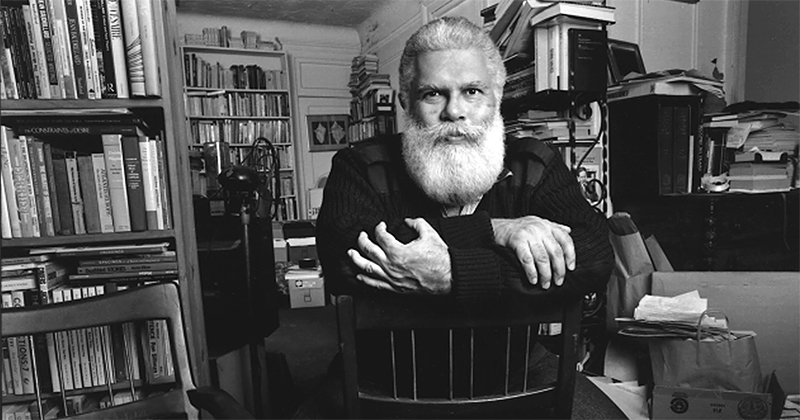

Samuel R. Delany

Samuel R. Delany

Delany is kind of a pre-cyberpunk hero, a hoary grandfather of science fiction who is also its disruptive queer upstart. His writing is amazing and incredibly difficult—the mammoth Dhalgren is a kind of SF shibboleth—and as we all know, everything that’s good is made even better when other people (especially when those people are one’s parents) don’t quite get it.

Luc Sante

Luc Sante

Chronicler of the New York slums, historian of 19th century lowlife, exceptional literary stylist. Read anything by him, but if you only have a few minutes, try, “The Party,” which begins like this:

Maybe the party began at Max’s, circa 1966, or at the Factory around ’63—deciding on a point of origin would be like trying to say who got the first hangover. In any case, by the mid-70’s, the party was no longer an event but an institution, and pretty near the only one around. The city then was a ruin inhabited by scavengers, and going anywhere else involved some form of space travel. The night was dark, the streets were empty, the taxis were nowhere to be found, but there, all lighted up at the bottom of the alley, was the party. It was very, very loud. People had X’s in place of eyes. Watches stopped working just inside the door. Saturday night could stretch into Wednesday. Drink tickets were legal tender, and dollars were good mainly for rolling into cylinders. Friendships were forged that might last for hours, possibly days. Your coat, tossed in a corner, was as good as gone. If you were at the party, chances are that you remember it in discontinuous flashes, if at all.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.