11 Legendary Literary Parties We’re Sad to Have Missed

Booze, Books, and Oh Yes, Bad Behavior

Everyone loves a good party. Especially literary people—who, aside from book parties, which technically count as “work” (ask their accountants) tend not to get out much. Or so the stories go. Literature abounds with great parties, but here I’m interested in the parties that actually took place in literary history—where famous authors met, or fought, or fell asleep, or got goaded into writing mega-famous, bestselling memoirs. Eleven of these historically relevant literary events are below, for all your FOMO/vicarious partying needs.

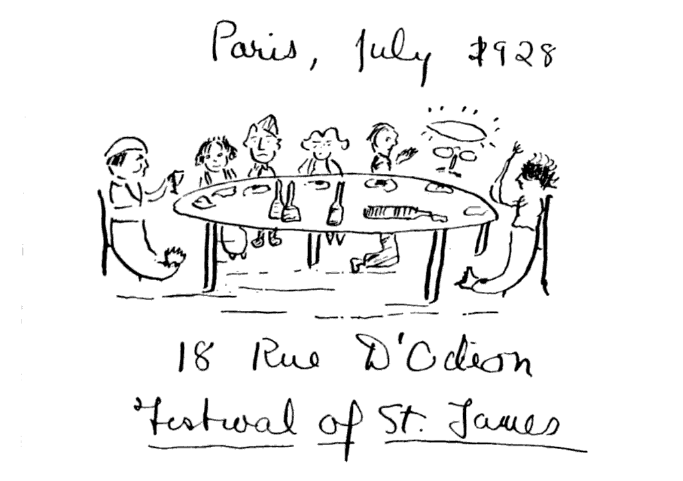

The Festival of St. James; or, when Sylvia Beach hosted a dinner party so that F. Scott Fitzgerald could meet James Joyce

On June 27th, 1928, Sylvia Beach, the founder of Shakespeare and Company, and first publisher of Ulysses, threw a little dinner party with her partner, and they invited a few of their American friends. Simple enough. But there was an underlying motive, as she wrote in her memoir:

Adrienne was as interested as I was in the American writers who were in and out of my bookshop, and we shared them all. There should have been a tunnel under the rue de l’Odéon.

One of our great pals was Scott Fitzgerald—see the snapshot I took of him and Adrienne sitting on the doorstep of Shakespeare and Company. We liked him very much, as who didn’t? With his blue eyes and good looks, his concern for others, that wild recklessness of his, and his fallen-angel fascination, he streaked across the rue de l’Odéon, dazzling us for a moment.

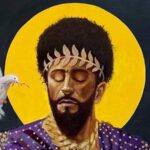

Scott worshiped James Joyce, but was afraid to approach him, so Adrienne cooked a nice dinner and invited the Joyces, the Fitzgeralds, and André Chamson and his wife, Lucie. Scott drew a picture in my copy of The Great Gatsby, of the guests—with Joyce seated at the table wearing a halo, Scott kneeling beside him, and Adrienne and myself, at the head and foot, depicted as mermaids (or sirens). [Ed. note: see the picture above]

“It is said,” wrote Beach biographer Noel Riley Fitch, “that he offered to show his esteem for the Irish writer (whom he addressed as “Sir”) by jumping out of the window. An amazed Joyce is supposed to have prohibited the display and exclaimed, “That young man must be mad—I’m afraid he’ll do himself some injury.” And according to still another source, Fitzgerald knelt before Joyce, “kissed his hand, and declared: “How does it feel to be a great genius, Sir? I am so excited at seeing you, Sir, that I could weep.”” Well, at least he got an autograph, and we got this little doodle.

The party where Sylvia Plath met Ted Hughes

On February 25th, 1956, the St. Botolph’s Review held a launch party in Cambridge; it would be a fateful, famous event in the literary world, but probably not for the reasons they hoped. As Belinda McKeon writes:

Hughes wrote, afterwards, to his friend Terence McCaughey, making no mention of having encountered Plath, but talking about the “large fine room” it was held in, the meeting-room of the Women’s Union, a venue which had assured the magazine editors a large female attendance: “all drank, more women than men, we left the place smashed, windows out, polished floor like a dirt-track.” Meanwhile, to his parents: “I went to a Party in Cambridge the other weekend, which was very bright, and everything got smashed up.”

. . .

Sylvia Plath, then 23 years old, was a Fulbright scholar at Newnham, and she wrote to her mother several times a week, letters which endeavored to cast an intensely positive, high-achieving glow on her experiences, writing her life up like a progress report, making sure to thank her generous sponsors: “I do want to tell you now how much your letters mean to me,” she told her mother in that post-party missive. “Last Monday those phrases you copied from Max Ehrmann came like milk-and-honey to my weary spirit; I’ve read them again and again. Isn’t it amazing what the power of words can do?” Signing off, Plath mentioned, almost casually, that she had met, “by the way, a brilliant ex-Cambridge poet at the wild St. Botolph’s Review party last week; will probably never see him again . . . but wrote my best poem about him afterwards—the only man I’ve met yet here who’d be strong enough to be equal with—such is life.”

. . .

In many ways, then, they were primed for each other, these two young poets. For all the outward confidence with which they seem to have turned up at the party, each of them needed to find something or someone who would create for them the possibility of breaking through, of release. This may be why they both wrote of the night in language stormed by verbs of crashing, of banging, of smashing and shouting and noise; it may be why Hughes needed to account for it in astrological terms; it may be why Plath needed to believe that she had bit so hard into Hughes’s cheek as he kissed her neck that she left, not just a mark (Hughes describes it in the poem as a “ring-moat of tooth marks”), but an open wound, dripping blood. How hard would you need to bite someone’s face, and with what incisoral talent, and with what kind of leverage, to leave them with “blood running down his face,” as Plath, high as a kite, wrote in her journal the next morning? And yet that legend has endured. Which shows that Plath was not the only one who has needed to believe it.

And that “best poem” Plath wrote after meeting Hughes? She titled it “Pursuit” and it begins like this:

There is a panther stalks me down:

One day I’ll have my death of him;

Unfortunately, she was right.

The Poets & Writers party where Richard Ford spat on Colson Whitehead

As previously reported in this space: In 2002, Colson Whitehead reviewed Richard Ford’s A Multitude of Sins for the New York Times Book Review. It was not a positive review. “Almost every story deals with adultery, invariably in one of two stages: in the final dog days of an affair, or in the aftermath of an affair,” Whitehead wrote.

The characters are nearly indistinguishable. If I were an epidemiologist, I’d say that some sort of spiritual epidemic had overtaken a segment of our nation’s white middle-class professionals, and has started to afflict white upper-middle-class professionals. These characters could use some good advice, and if they had friends, they might be able to ask for it, but they don’t have friends. Sometimes the men are named Roger or Tom, sometimes the women are named Nancy or Frances. If they have children, we rarely see them. Some of them meet in fancy hotel rooms, others prefer out-of-the-way motels. Whatever the specifics, adulterous or not, they bide their time for opportunities to offer portentous declarations about their predicaments like: ‘Other people affect you. It’s really no more complicated than that’ and ‘I am sure now that all of this had to do with my impending failures.’ These declarations will strike you as plain-spoken and hard-earned wisdom, or easy banalities, depending on your mood or level of generosity.

Two years later, Ford was still pissed enough to approach Whitehead at a Poets & Writers party. “I’ve waited two years for this,” he said. “You spat on my book.” Then he spat on Whitehead. Reporting this to Deborah Schoenman, Whitehead said, “We had a few heated words—he said, ‘You’re a kid, you should grow up,’ which coming from him was a bit funny—and then he stalked off. This wasn’t the first time some old coot had drooled on me, and it probably won’t be the last. But I would like to warn the many other people who panned the book that they might want to get a rain poncho, in case of inclement Ford.”

Fifteen years on, Ford is sticking to his guns. “I realize that how I feel about my bad treatment is only one compass point among several legitimate ones,” he wrote in Esquire last summer. “But I can tell you that, as of today, I don’t feel any different about Mr. Whitehead, or his review, or my response.” Most people think he’s rather in the wrong.

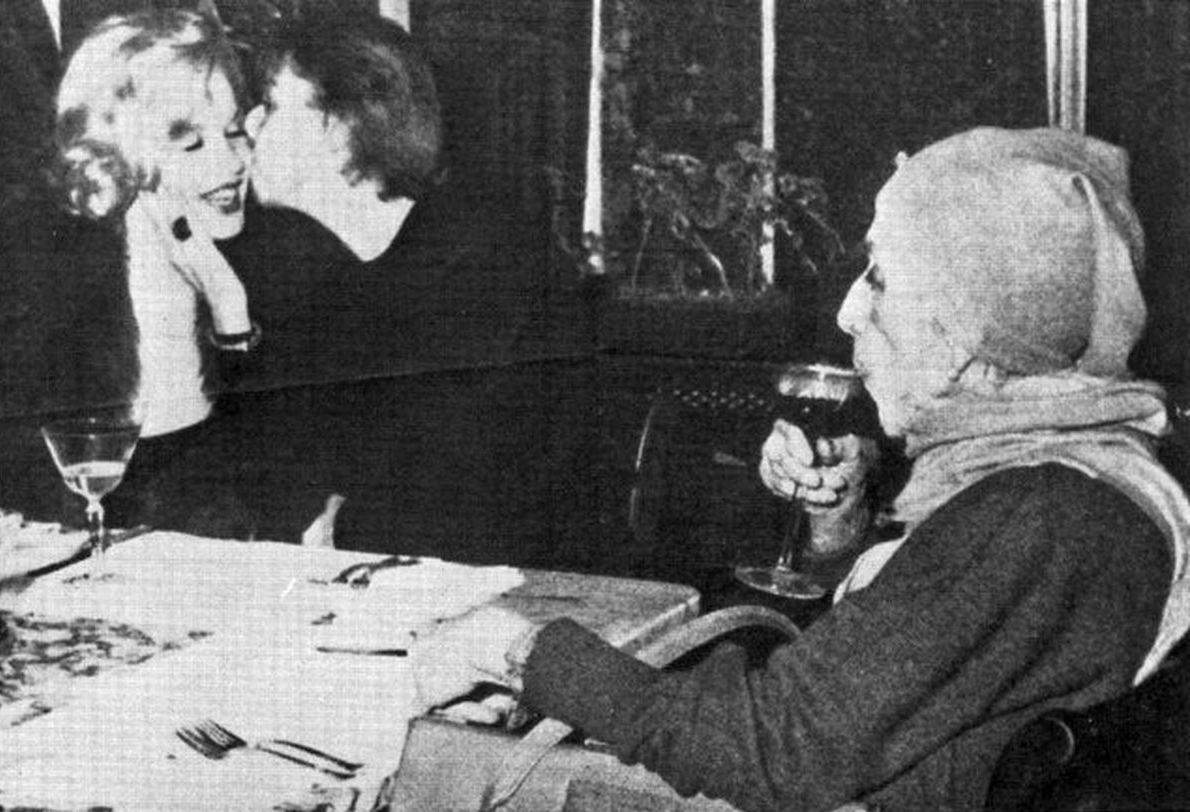

When Carson McCullers entertained Karen Blixen (aka Isak Dinesen) and Marilyn Monroe

According to biographer Virginia Spencer Carr, writing in The Lonely Hunter, in the first weeks of 1959, Carson attended one of Blixen’s literary events, and when they met at the dinner afterwards, Blixen told Carson that the only people she wanted to meet in America were e.e. cummings, Ernest Hemingway, Marilyn Monroe, and Carson herself. Hemingway, alas, was out of the country, and cummings was covered, and here was Carson—who said she could easily introduce her to Monroe, who was a friend (how simple!). She declared that she would host a luncheon and invite Blixen as well as Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe. She arranged the party for February 5th, and after being informed by Blixen’s assistant that she “ate only oysters and white grapes and drank only champagne,” made sure these things were in abundance. “After the oysters and champagne—there had been soufflé for the others—Carson reportedly put music on the phonograph and invited Miss Monroe and Miss Dinesen to join her in dancing on the marble-topped dining-room table,” Carr writes.

Both Jordan Massee and Arthur Miller are certain, however, that such antics did not take place in actuality. “I cannot believe that either Carson or Miss Dinesen could have danced, given their physical condition, let alone on top of a table,” said Miller. Nevertheless, Caron cherished the tale and told it often. It had been years since she had entertained with such frivolity or felt such childlike pleasure and wonderment at the love which her guests seemed to express that day for each other. . . . To Carson, it was one of the best parties she had ever given. Although Arthur Miller was never to know Carson well, his memory of the luncheon remained vivid. Of Marilyn Monroe, who killed herself three years later (she and Miller were divorced in 1961), Miller said: “I do not know that Marilyn had ever read any of Carson’s works, although she may well have seen her play The Member of the Wedding. However, at the luncheon there was certainly a sort of natural sympathy between the two women who lived close to death.

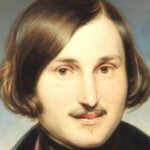

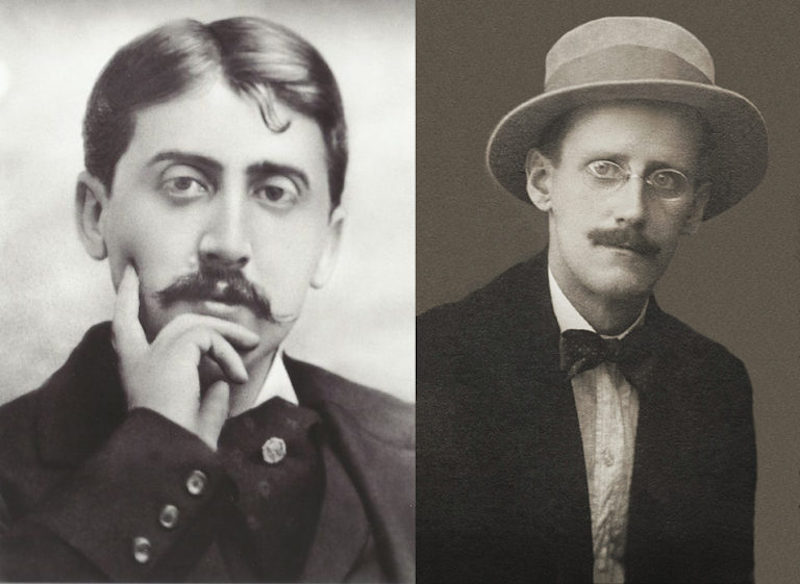

When Marcel Proust came to a party at 2:30 in the morning to meet James Joyce, who was asleep

But it’s fair to say that Joyce wasn’t always such a hit at parties. As noted before in this space, Proust and Joyce met when they were set up on a blind date of sorts—a four-way blind date that also included Pablo Picasso and Igor Stravinsky. The party was arranged by British art patrons Sydney and Violet Schiff, who had, according to Craig Brown’s Hello Goodbye Hello, “been plotting to gather the four men they consider[ed] the world’s greatest living artists in the same room.” Proust showed up around 2:30 in the morning, and when Joyce woke up, they were introduced. There are many accounts of what followed, but all of them are bad. Joyce told his friend Frank Budgen that “Our talk consisted solely of the word ‘No.’ Proust asked me if I knew the duc de so-and-so. I said, ‘No.’ Our hostess asked Proust if he had read such and such a piece of Ulysses. Proust said, ‘No.’ And so on. Of course the situation was impossible. Proust’s day was just beginning. Mine was at an end.” But William Carlos Williams and Ford Madox Ford, who were both on hand, agree that the two men did exchange more words than that—if only about their many complaints and illnesses.

The dinner at which The Atlantic was founded

In 1857, publisher Moses Phillips held a dinner party to pitch the idea for The Atlantic (originally The Atlantic Monthly) to some leading literary lights. He described it in a letter to his niece:

I must tell you about a little dinner-party I gave about two weeks ago. It would be proper, perhaps, to state that the origin of it was a desire to confer with my literary friends on a somewhat extensive literary project, the particulars of which I shall reserve till you come. But to the party: My invitations included only R.W. Emerson, H.W. Longfellow, J.K. Lowell, Mr. Motley (the ‘Dutch Republic’ man), O.W. Holmes, Mr. Cabot, and Mr. Underwood, our literary man. Imagine your uncle as the head of such a table, with such guests. The above named were the only ones invited, and they were all present. We sat down at three P.M., and rose at eight. The time occupied was longer by about four hours and thirty minutes than I am in the habit of consuming in that kind of occupation, but it was the richest time intellectually by all odds that I have ever had. Leaving myself and ‘literary man’ out of the group, I think you will agree with me that it would be difficult to duplicate that number of such conceded scholarship in the whole country beside.

Mr. Emerson took the first post of honor at my right, and Mr. Longfellow the second at my left. The exact arrangement of the table was as follows:

Mr. Underwood.

Cabot. Lowell.

Motley. Holmes.

Longfellow. Emerson.

Phillips.

They seemed so well pleased that they adjourned, and invited me to meet them again to-morrow, when I shall again meet the same persons, with one other (Whipple, the essayist) added to that brilliant constellation of philosophical, poetical, and historical talent. Each one is known alike on both sides of the Atlantic, and is read beyond the limits of the English language. Though all this is known to you, you will pardon me for intruding it upon you. But still I have the vanity to believe that you will think them the most natural thoughts in the world to me. Though I say it that should not, it was the proudest day of my life.”

“In this letter he does not tell of his own little speech, made at the launch,” writes biographer Edward Everett Hale. “But at the time we all knew of it. He announced the plan of the magazine by saying, ‘Mr. Cabot is much wiser than I am. Dr. Holmes can write funnier verses than I can. Mr. Motley can write history better than I. Mr. Emerson is a philosopher and I am not. Mr. Lowell knows more of the old poets than I.’ But after this confession he said, ‘But none of you knows the American people as well as I do.'” And thus The Atlantic was born.

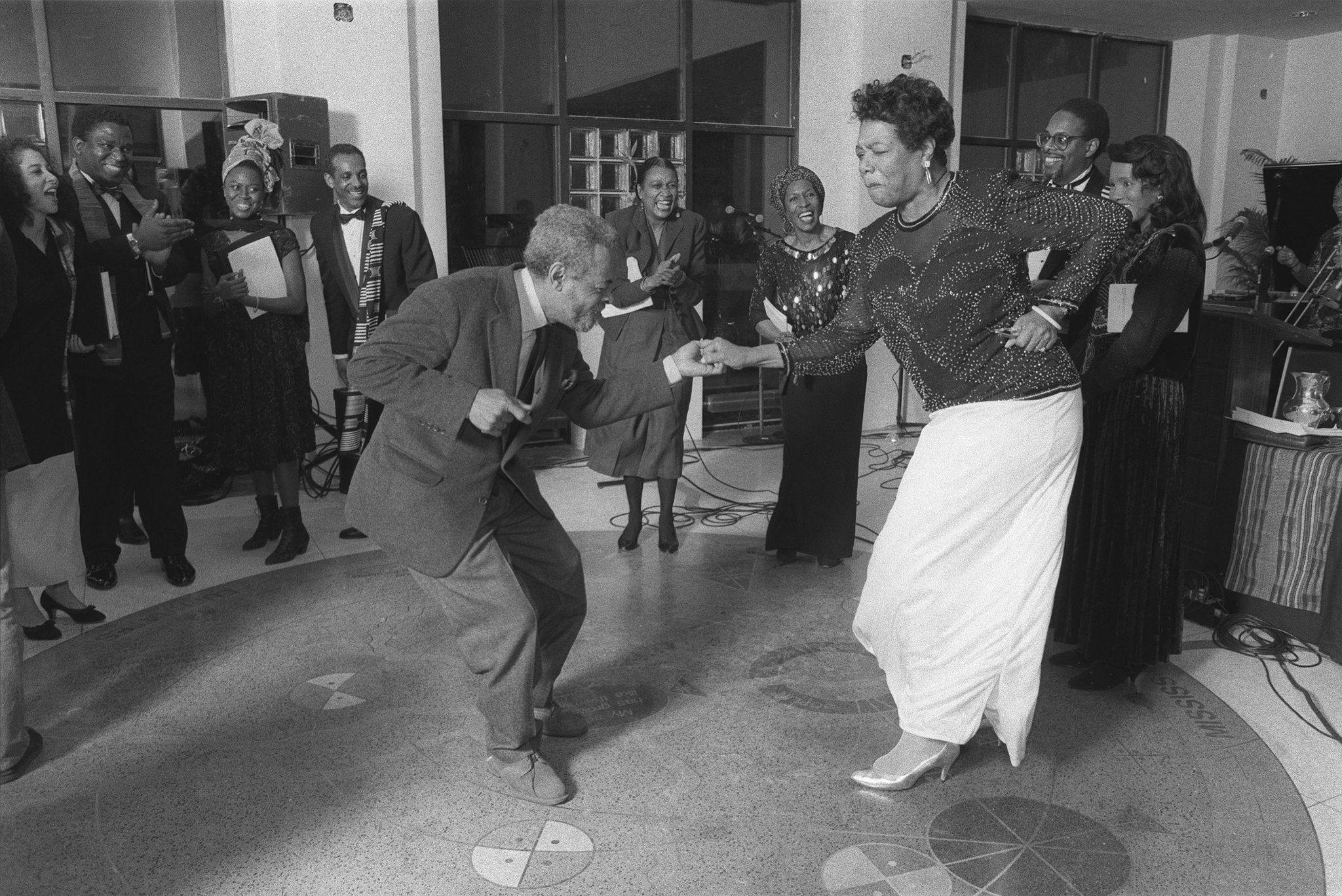

Maya Angelou in 1991, dancing with the poet Amiri Baraka. Chester Higgins Jr./The New York Times

Maya Angelou in 1991, dancing with the poet Amiri Baraka. Chester Higgins Jr./The New York Times

The party that led to I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

Perhaps this party itself isn’t particularly legendary—but the memoir that came out of it is. As Sam Roberts writes in The New York Times:

To hearten Ms. Angelou [after the death of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on her 40th birthday], her friend James Baldwin took her to dinner at [Judy Feiffer’s] Manhattan apartment. There, she entranced the host couple, the novelist Philip Roth, and the other guests with her stories, many of them harrowing, of growing up in the segregated South, being raped by her mother’s boyfriend and, after being shuttled among relatives, her pervasive sense of displacement, which, for a black girl, she recalled, was “the rust on the razor that threatens the throat.”

“Her stories were fascinating, and Angelou was intoxicatingly charismatic and dynamic in the telling of them,” Kate Feiffer said this week. “My mother urged her to write a memoir.”

Ms. Angelou demurred, but Judy Feiffer introduced her to Robert Loomis, an editor at Random House. She resisted his entreaties, too. But, Ms. Angelou recalled at a tribute to Mr. Loomis in 2007 that the editor shrewdly tried another gambit. It was too challenging for Ms. Angelou to resist.

“It’s just as well, because to write an autobiography as literature is just impossible,” Mr. Loomis said. To which Ms. Angelou replied gamely, “I will try.”

Obviously, she succeeded.

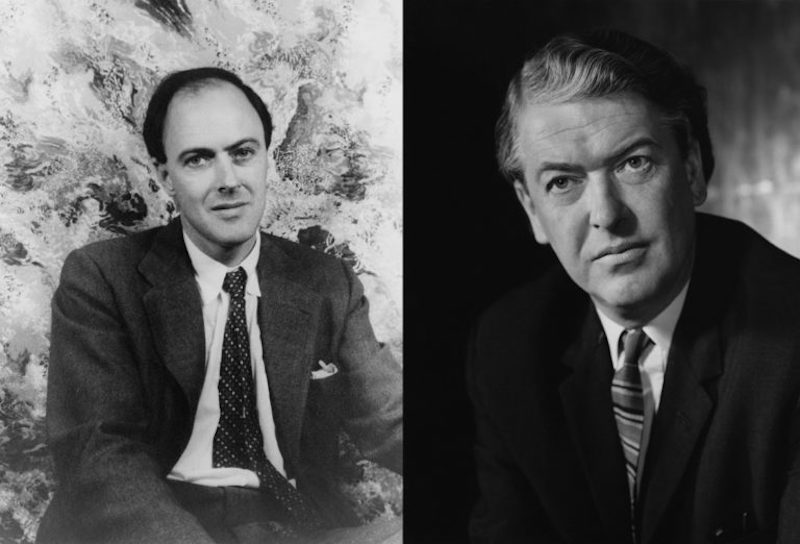

When Roald Dahl met Kinglsey Amis at Tom Stoppard’s house, and they hated each other

As previously noted in this space, Roald Dahl and Kingsley Amis met at a party thrown by Tom Stoppard in 1972, and they did not get along. Apparently, Dahl immediately began talking about money, and suggested to Amis that if he really wanted to make the big bucks as a writer, that he should try his hand at writing books for children. The tension was palpable. Donald Sturrock, Dahl’s biographer, wrote that “Amis, who had no interest in children’s fiction, felt he was being patronized by Dahl’s suggestion that his own writing was not bringing him enough money. Dahl, for his part, was in precisely the kind of English literary environment he loathed. He knew that Amis, like most of the guests, did not respect children’s writing as proper literature and this attitude made him feel vulnerable.”

According to his memoirs, Amis demurred, “I’ve got no feeling for that kind of thing,” and Dahl retorted, “Never mind, the little bastards’d swallow it,” before jumping into his helicopter and leaving the scene. “I watched the television news that night,” Amis writes, “but there was no report of a famous children’s author being killed in a helicopter crash.”

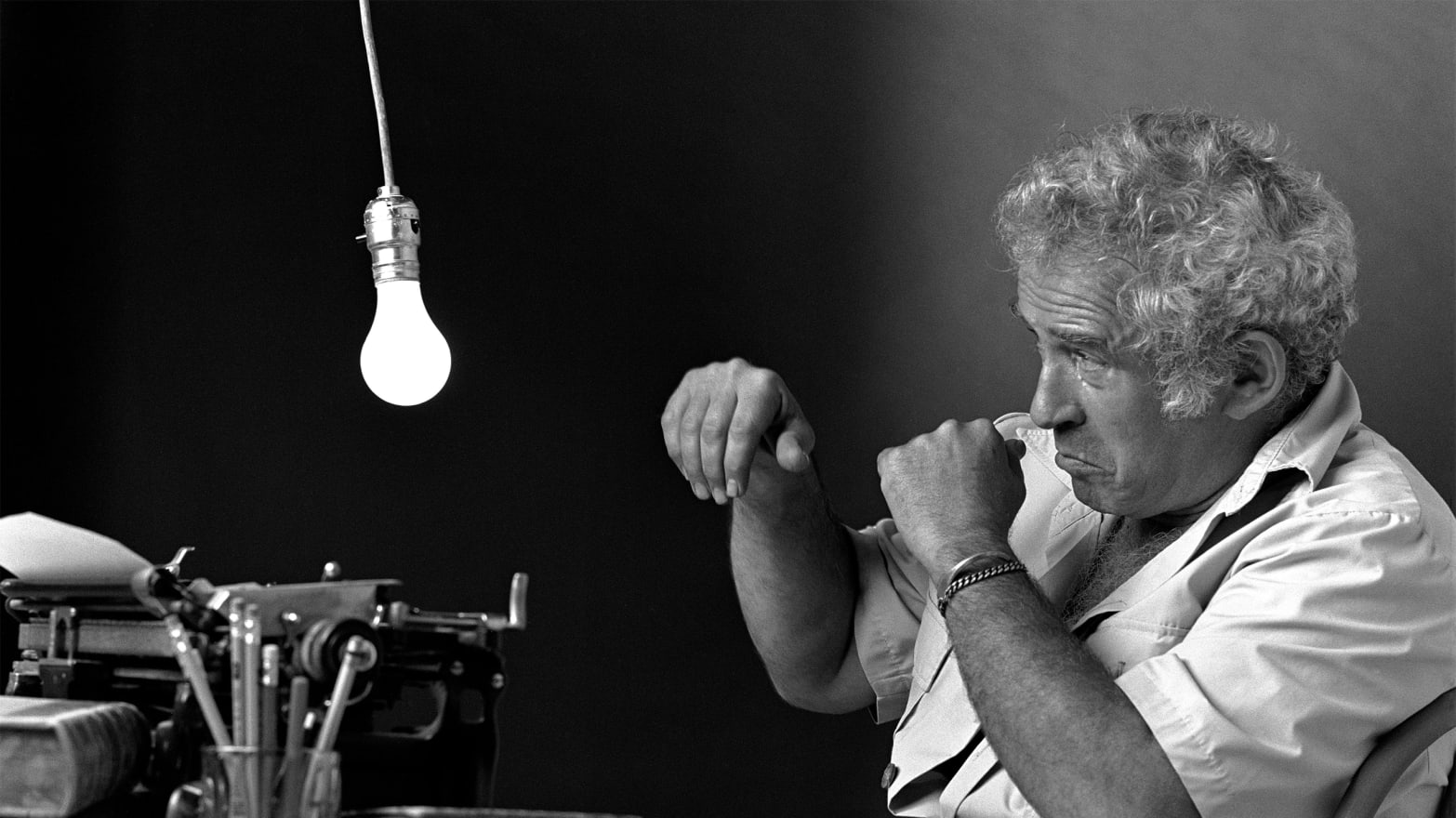

The party where Norman Mailer punched Gore Vidal, who landed his own legendary wallop

Everyone knows that Norman Mailer was something of a pugilist, to put it mildly. One of his most famous feuds was with Gore Vidal, whom he head-butted before a joint performance on the Dick Cavett Show in 1971. It was six years later, as legend has it, that Mailer managed to punch Vidal to the floor at a party in New York. A blessing in disguise (for us) because it opened the door to one of the best insults in literary history. “Once again words fail Norman Mailer,” said Vidal before getting back to his feet. I mean, snap, amirite.

The Paris Review party, as monolith

I would venture that the most famous literary party is still “the Paris Review party,” a phrase that might refer to any of the five decades of parties George Plimpton threw at his apartment, or all of them collectively, or all of them plus, to a lesser degree, the decade and a half of parties since his death. “The typical [Plimpton] party had a few key ingredients,” wrote Warren St. John in 2003, “an easygoing but suspenseful vibe, given that no one knew who might show up; an open door—Mr. Plimpton despised guest lists; a minimalist selection of hors d’oeuvres laid out on the pool table; and an anachronistic offering of liquor that served as a kind of call-to-arms to revelry.

In the early days of Mr. Plimpton’s parties, guests included friends like Truman Capote, William Styron, Ralph Ellison, Lewis Lapham and Gore Vidal. He insisted on giving book parties for anyone who had been published in his magazine, which over time included Rick Bass, Mona Simpson and Jay McInerney, among others. Eventually, Manhattan publishing houses simply relied on Mr. Plimpton to give parties for their authors; the publishers would supply the drinks and food, and Mr. Plimpton the venue and the excitement. Crashing these parties was a rite of passage for generations of young aspiring writers and editors, who saw them as an opportunity to rub elbows with literary giants like Norman Mailer and Gay Talese.

”I think when people went, they thought, ‘This is why I came to New York,’ ” said Helen Schulman, who went to her first Plimpton party while an M.F.A. student at Columbia and who has published three novels. (Ms. Schulman spent a decent portion of her own book party at Mr. Plimpton’s locked in the bathroom; her desperate banging on the door could not be heard over the din of the party just outside.)

Or perhaps, as it sometimes goes, the most famous party would be the last one thrown in Plimpton’s apartment, after his death, by his widow, as a sort of goodbye.

And last but not least, but of course: Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball

I mean, the paper of record has called Capote’s Black and White Ball “the best party ever.” It was November 28, 1966, and 540 people turned up for the (nonfiction) novelist’s “little masked ball for Kay Graham and all of my friends.” Was the party itself particularly literary? Who cares? Capote is literary enough for everybody.

Previous Article

Richard Russo: On the MoralPower of Regret