100 Covers of Gabriel García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude

Iconic Covers, from 1967 to Today

Pablo Neruda once called Gabriel García Márquez’s 1967 novel One Hundred Years of Solitude “perhaps the greatest revelation in the Spanish language since the Don Quixote of Cervantes.” Now a beloved classic for millions, and the defining pinnacle of magical realist literature, the novel traces the Buendía family over seven generations spent in their fictional hometown of Macondo—founded in the Colombian rainforest by their patriarch, José Arcadio Buendía—which is reportedly based on Márquez’s own hometown of Aracataca, near the northern coast of Colombia. For a while it is a kind of utopia, though a strange one, but eventually, the encroachment of the outside world destroys everything the Buendías have built. This is a lush, descriptive, and relentlessly irreal novel, and as such, its cover treatments have varied wildly over the years. Below, I’ve selected one hundred different covers used for One Hundred Years of Solitude, published around the world between 1967 and 2018. The only question is: which one is the best?

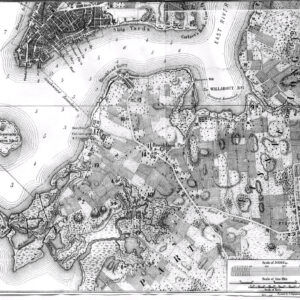

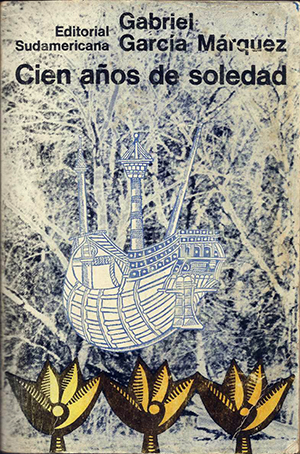

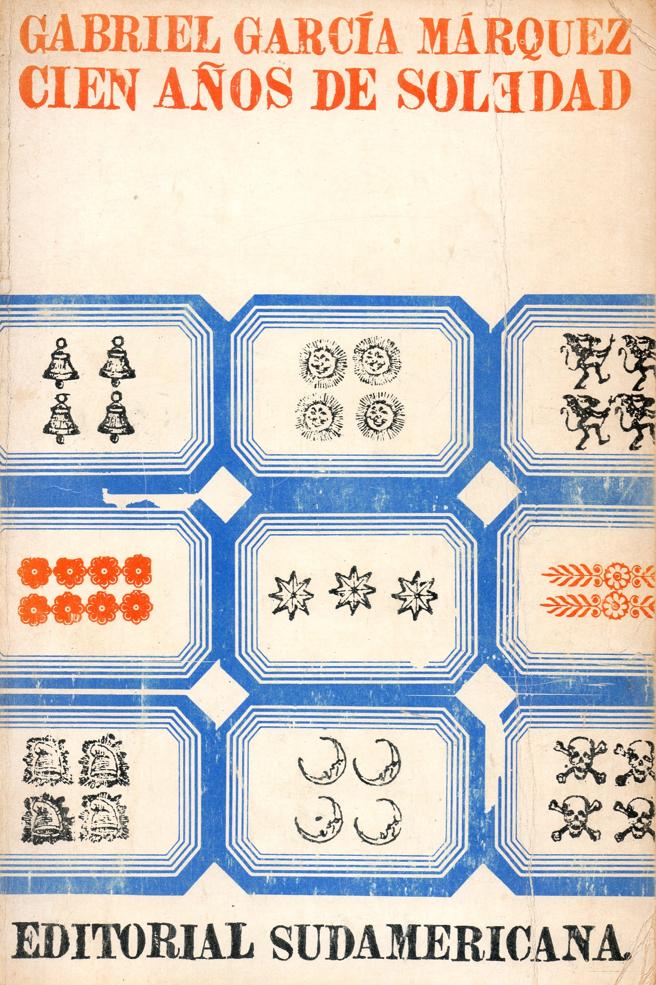

Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, 1967

Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, 1967

The very first edition draws directly from one of the book’s earliest images: “When they woke up, with the sun already high in the sky, they were speechless with fascination. Before them, surrounded by ferns and palm trees, white and powdery in the silent morning light, was an enormous Spanish galleon. Tilted slightly to the starboard, it had hanging from its intact masts the dirty rags of its sails in the midst of its rigging, which was adorned with orchids. The hull, covered with an armor of petrified barnacles and soft moss, was firmly fastened into a surface of stones. The whole structure seemed to occupy its own space, one of solitude and oblivion, protected from the vices of time and the habits of the birds. Inside, where the expeditionaries explored with careful intent, there was nothing but a thick forest of flowers.”

Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana 1967

Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana 1967

García Márquez liked this edition so much he wore it as a hat.

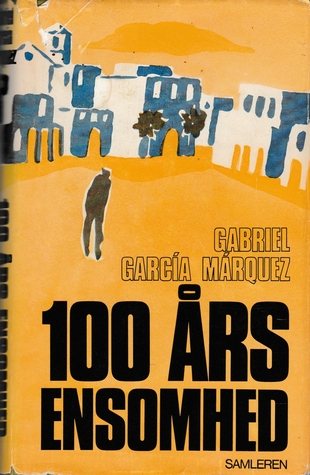

Samleren, 1969

Samleren, 1969

This Norwegian edition has the dream-scape feel down—particularly José Arcadio Buendía’s dream of a village made from ice-block houses.

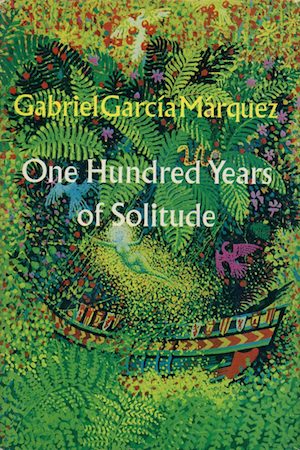

New York: Harper & Row, 1970

New York: Harper & Row, 1970

First American edition. Beautiful, magical, and lush, like the novel; the more you look at it, the more details you notice: the birds, the snake, the fairy, the ferns, that galleon again.

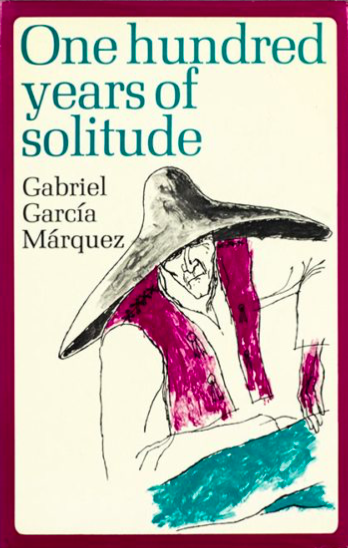

London: Jonathan Cape, 1970

London: Jonathan Cape, 1970

A rendering, perhaps, of the gypsy Melquíades: “That prodigious creature, said to possess the keys of Nostradamus, was a gloomy man, enveloped in a sad aura, with an Asiatic look that seemed to know what there was on the other side of things. He wore a large black hat that looked like a raven with widespread wings, and a velvet vest across which the patina of the centuries had skated.”

Avon Books, 1970

Avon Books, 1970

Talk about the heat of the jungle.

Publicações Europa-América, 1971

Publicações Europa-América, 1971

I can’t say I understand this one—the policemen armed with wooden clubs?—but I find it deeply appealing, both in terms of design and color combination.

Отечествения фронт, 1971

Отечествения фронт, 1971

A clever representation of the novel’s obsession with time, ghosts, love both familial and romantic, and the endless repetition of history.

Meulenhoff, 1972

Meulenhoff, 1972

That is one large foot.

Meulenhoff, 1972

Meulenhoff, 1972

“Aureliano, who could not have been more than five at the time, would remember him for the rest of his life as he saw him that afternoon, sitting against the metallic and quivering light from the window, lighting up with his deep organ voice the darkest reaches of the imagination. . .”

Penguin Books Ltd, 1972

Penguin Books Ltd, 1972

What new gypsy invention is this?

Feltrinelli, 1973

Feltrinelli, 1973

That galleon again—but something about this Italian cover makes me think more of J. G. Ballard than García Márquez.

Editura Minerva, 1974

Editura Minerva, 1974

“‘Those kids are out of their heads,’ Úrsula said. ‘They must have worms.'”

Eesti Raamat, 1975

Eesti Raamat, 1975

Melquíades again, in his raven hat.

Círculo de lectores, 1975

Círculo de lectores, 1975

There’s nothing more daring and alluring (in book cover design, anyway) than leaving the title and author off completely and treating the cover like unfettered art.

Magvető, 1975

Magvető, 1975

I admit I have no idea what is going on here, but at least the birds are still alive—for now.

Penguin, 1977

Penguin, 1977

I’m not sure which painting this is sourced from, but to me it doesn’t exactly strike the right note.

Literackie, 1977

Literackie, 1977

Perhaps one of these hidden creatures is in fact Aureliano Segundo, dressed up as a tiger?

London: Picador/Pan Books, 1978

London: Picador/Pan Books, 1978

About the closest to a normal-looking family portrait this lot is likely to get.

Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, 1978

Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, 1978

Your face here.

BIGZ, 1978

BIGZ, 1978

A winged soldier riding a tail-less horse made of the universe over guns and hearts and flowers. This seems about right.

Издателство на Отечествения фронт, 1978

Издателство на Отечествения фронт, 1978

“‘A person can’t go on in neglect like this,’ she said. ‘If we go on like this we’ll be devoured by animals.'”

La oveja negra, 1979

La oveja negra, 1979

A family both ghost and not.

P.I.W., 1979

P.I.W., 1979

How long can one be tied to a chestnut tree before one actually becomes a tree oneself?

Εκδόσεις Νέα Σύνορα- Α. Λιβάνης, 1979

Εκδόσεις Νέα Σύνορα- Α. Λιβάνης, 1979

The bowler seems very incongruous here.

Editions du Seuil, 1980

Editions du Seuil, 1980

A lovely vision of Macondo.

BIGZ, 1982

BIGZ, 1982

“At that time Macondo was a village of twenty adobe houses, built on the bank of a river of clear water that ran along a bed of polished stones, which were white and enormous, like prehistoric eggs. The world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point.”

De norske bokklubbene, 1983

De norske bokklubbene, 1983

It’s a little bit like how I imagine the entrance to Wakanda: a break in the landscape so slim you might miss it—but if you don’t, there’s a world of magic on the other side.

Euroclub, 1983

Euroclub, 1983

This painting is Diego Rivera’s “The Flower Seller” (1942).

Editora Record, 1985

Editora Record, 1985

This looks like an ancient Roman text and makes no sense for this book, but I still find it pretty compelling.

Kazakh edition, 1985

Kazakh edition, 1985

A tree or a continent (or both)?

BIGZ, 1985

BIGZ, 1985

Another image that makes no sense for this novel, but is weird enough on its own that I can’t help but kind of like it.

Círculo de Leitores, 1988

Círculo de Leitores, 1988

Those river eggs again—plus a little mini green Gabo surveying the scene.

Sudamericana, 1991

Sudamericana, 1991

“He tried to seduce her with the charm of his fantasy, with the promise of a prodigious world where all one had to do was sprinkle some magic liquid on the ground and the plants would bear fruit whenever a man wished, and where all manner of instruments against pain were sold at bargain prices.”

Moldova, 1992

Moldova, 1992

“Then the wind began, warm, incipient, full of voices from the past, the murmurs of ancient geraniums, sighs of disenchantment that preceded the most tenacious nostalgia.”

P.I.W., 1992

P.I.W., 1992

Another living tree—Tolkien would be proud.

Meulenhoff, 1992

Meulenhoff, 1992

The yellow works—the teal is kind of a stretch.

Wahlström & Widstrand, 1994

Wahlström & Widstrand, 1994

“It was then that she realized that the yellow butterflies preceded the appearances of Mauricio Babilonia. She had seen them before, especially over the garage, and she had thought that they were drawn by the smell of paint. Once she had seen them fluttering about her head before she went into the movies. But when Mauricio Babilonia began to pursue her like a ghost that only she could identify in the crowd, she understood that the butterflies had something to do with him. Mauricio Babilonia was always in the audience at the concerts, at the movies, at high mass, and she did not have to see him to know that he was there, because the butterflies were always there.”

A. Mondadori, 1995

A. Mondadori, 1995

Very pretty—and perhaps slightly too delicate for the subject at hand.

Everyman’s Library, 1995

Everyman’s Library, 1995

There he is.

RAO, 1995

RAO, 1995

A very surrealist interpretation of a family gathering.

Grupo Editorial Norma, 1996

Grupo Editorial Norma, 1996

I don’t know what these little red-faced creatures are, but they seem right at home.

Auflage: N.-A, 1996

Auflage: N.-A, 1996

Boilerplate dream-town.

Wahlström & Widstrand, 1996

Wahlström & Widstrand, 1996

An image reused from a previous year—this time you can better see the skull.

Kiepenheuer und Witsch, 1997

Kiepenheuer und Witsch, 1997

A verdant jungle scene.

Gyldendal, 1997

Gyldendal, 1997

I like this weird and oversaturated take on jungle life—including the half lemon and plantain (I think) balanced so delicately on the railing.

Perennial, 1998

Perennial, 1998

Or do I dream? Or have I dreamed till now?

Uitgeverij Meulenhoff, 1998

Uitgeverij Meulenhoff, 1998

Again with the boat; this time sinking into a blood-read sea; this time with a ghostly face.

Penguin Books, 1999

Penguin Books, 1999

I love this depiction of the land as a living creature—and not just living, but with very shapely legs.

Penguin, 2000

Penguin, 2000

Perhaps the sexiest of all the One Hundred Years of Solitude covers. Because of the monkey, obviously.

Inne, 2000

Inne, 2000

Sure: a horse with hair like a girl’s and a tower growing out of its head.

Mondadori, 2000

Mondadori, 2000

Can double as an outdated bathroom sign.

Dom Quixote, 2000

Dom Quixote, 2000

“He soon acquired the forlorn look that one sees in vegetarians.”

MUZA SA, 2001

MUZA SA, 2001

“Gaston was not only a fierce lover, with endless wisdom and imagination, but he was also, perhaps, the first man in the history of the species who had made an emergency landing and had come close to killing himself and his sweetheart simply to make love in a field of violets.”

Астрель, 2002

Астрель, 2002

“In a short time he filled not only his own house but all of those in the village with troupials, canaries, bee eaters, and redbreasts. The concert of so many different birds became so disturbing the Úrsula would plug her ears with beeswax so as not to lose her sense of reality. The first time that Meliquíades’ tribe arrived, selling glass balls for headaches, everyone was surprised that they had been able to find that village lost int he drowsiness of the swamp, and the gypsies confessed that they had found their way by the song of the birds.”

Harper, 2003

Harper, 2003

This is the edition I’m most used to seeing—a slightly altered version of the first American edition.

Muza S.A., 2003

Muza S.A., 2003

It is a testament to my vast ignorance about South American iconography that I’m now thinking about Legends of the Hidden Temple.

Bentang Budaya, 2003

Bentang Budaya, 2003

Is that a yeti?

Magvető, 2003

Magvető, 2003

What is she running from?

Loisto: WSOY, 2003

Loisto: WSOY, 2003

Generations and generations and Aureliano’s little gold fishes.

Norma S a Editorial, 2003

Norma S a Editorial, 2003

Yellow butterflies are such a strong presence in this novel that mourners left paper versions outside García Márquez’s house when he died, and later at his memorial. I don’r remember a woman turning into one, but I wouldn’t put it past any of them.

RBA Editores, 2004

RBA Editores, 2004

“First they brought the magnet.”

Fischer Taschenbuch, 2004

Fischer Taschenbuch, 2004

Your standard jungle-esque art.

Can Yayınları, 2005

Can Yayınları, 2005

After all, this is a novel in which levitation can be achieved by means of hot chocolate.

دار المدى, 2005

دار المدى, 2005

Almost like a hand-painted door—the colors of houses being rather a touchy subject in Macondo. “We fought all those wars and all of it just so that we didn’t have to paint our houses blue.”

المؤسسة العربية للدراسات والنشر,2005

المؤسسة العربية للدراسات والنشر,2005

I think that crow is a lawyer.

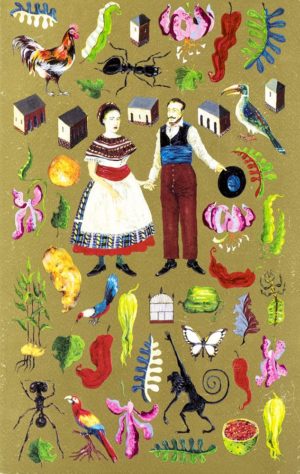

London: The Folio Society, 2006

London: The Folio Society, 2006

A very pretty box cover from the Folio Society—the hardcover inside is black with the two central figures above embossed in gold.

Harper Perennial Modern Classic, 2006

Harper Perennial Modern Classic, 2006

A classroom staple.

Shinchōsha, 2006

Shinchōsha, 2006

Perhaps too minimalist to be meaningful.

Alfaguara, 2007

Alfaguara, 2007

A leaf for every member of the family.

Odeon, 2008

Odeon, 2008

How did I miss the spaceships in this novel?

Points, 2008

Points, 2008

Macaws make great trading capital—but subpar dinner material.

Dom Quixote, 2009

Dom Quixote, 2009

A celebratory flourish of a cover.

Barnes & Noble, 2011

Barnes & Noble, 2011

A very convincing jungle scene—particularly that human-shaped stigma.

Nxb Văn Học & Minh Thắng, 2011

Nxb Văn Học & Minh Thắng, 2011

Well, there are baths taken in this novel.

Qanun Nəşriyyatı, 2011

Qanun Nəşriyyatı, 2011

Putting the numbers first.

АСТ, Астрель, Харвест, 2011

АСТ, Астрель, Харвест, 2011

Hmm.

Círculo de Lectores, 2011

Círculo de Lectores, 2011

There’s nothing like an artfully placed lotus flower.

Penguin Viking, 2014

Penguin Viking, 2014

A pretty shell pattern.

Penguin Books, 2014

Penguin Books, 2014

Girl with macaw.

Karo, 2014

Karo, 2014

Another one that looks like SF to me. What’s that coming down from the sky?

Wahlström & Widstrand, 2014

Wahlström & Widstrand, 2014

Somehow this colorful cutout gets the gist.

Rao Books, 2014

Rao Books, 2014

Another cover that plays on the theme of many connected or interlocking faces.

Can Yayınları, 2014

Can Yayınları, 2014

I shudder at the memory of those enormous red ants—it looks like one of them has escaped this book and is crawling across the cover towards your hand.

Debolsillo, 2014

Debolsillo, 2014

A very alluring entrance to a secret and magical world.

Literatura Random House, 2015

Literatura Random House, 2015

Another book cover playing on the tree theme.

Mondadori, 2015

Mondadori, 2015

But here’s an entirely different kind of tree.

Smashwords Edition, 2015

Smashwords Edition, 2015

The striations of the sun seem to get a little dirty down there at the bottom of the image.

Mondadori, 2016

Mondadori, 2016

I hear the gypsies have a trained monkey who can read minds.

NXB Văn Học, Huy Hoàng, 2016

NXB Văn Học, Huy Hoàng, 2016

A fair warning: in some towns, if you speak too much Latin, you’ll soon find yourself tied to a tree.

Literatura Random House, 2017

Literatura Random House, 2017

More red ants! And houses that are mere decorations for the vines.

민음사 , 2017

민음사 , 2017

“I don’t care if I have piglets as long as they can talk.”

Slovart, 2017

Slovart, 2017

Another pretty botanical treatment.

Meulenhoff Boekerij bv, 2017

Meulenhoff Boekerij bv, 2017

Macondo is a place overrun with birds—though they are not always as alive as they seem here.

Editora Record, 2017

Editora Record, 2017

There’s that yellow butterfly.

V. B. Z., 2017

V. B. Z., 2017

To be honest, this looks more like a moor than a rainforest.

Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 2017

Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 2017

One bird to represent many.

Eesti Raamat, 2017

Eesti Raamat, 2017

The eyes have it (or maybe they have the eyes).

Alma littera, 2017

Alma littera, 2017

More like a floating mountain village than a sweltering jungle one, but still a pretty treatment.

皇冠文化出版有限公司, 2018

皇冠文化出版有限公司, 2018

Maybe it’s just the glitter, but that looks like magic to me.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.