10 Wonderful Children's Poets You Should Know

In Honor of Shel Silverstein, Who Died 18 Years Ago Today

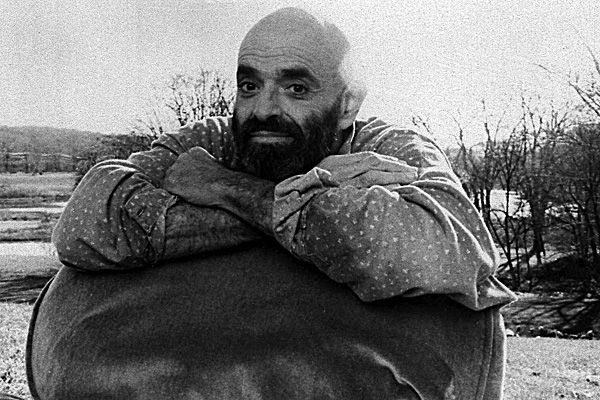

Eighteen years ago today, Shel Silverstein, also known as Uncle Shelby, also known as the writer who introduced a generation (or two) of current adults to poetry, died at the age of 67. Of course Silverstein did much more than simply write poems for children—he was also a songwriter, screenwriter, cartoonist, and general creative jack-of-all trades. As our friend Otto Penzler once put it,

[H]is whimsically hip fables, beloved by readers of all ages, have made him a stalwart of bestseller lists. A Light in the Attic, most remarkably, showed the kind of staying power on the New York Times chart—two years, to be precise— thought that most of the biggest names (John Grisham, Stephen King and Michael Crichton) have never equaled with their blockbusters. His unmistakable illustrative style is another crucial element to his appeal. Just as no writer sounds like Shel, no other artist’s vision is as delightfully, sophisticatingly cockeyed.

To celebrate Silverstein’s life and his most enduring contribution to all of ours, I’ve put together a brief (and obviously incomplete) survey of great children’s poets, starting, of course, with the man himself.

Shel Silverstein

Here’s something you may not know about Shel Silverstein: he hung out at the Playboy Mansion. Like, a lot. In the late ’50s and ’60s, Silverstein was a regular contributor to Playboy as a cartoonist, and his work continued to appear until his death (and one piece was published posthumously). According to this (faintly horrifying, but informative) remembrance:

As part of Hef’s inner circle and one of its court jesters, Silverstein might spend weeks or months at a time at the infamous party pad, where he tended to lurk in the background and let others come to him. Silverstein had no patience for bores . . . but he fed creatively off the many interesting people and encounters he had in the Playboy world—and he wrote many of his children’s works while inside it. As playwright David Mamet told The New York Times after Silverstein’s death: “He was Hugh Hefner’s sidekick, he was the great cartoonist, he lived with Hef at the Playboy Mansion, in a riot of delight.”

Happily, he was the court jester for more than just the Playboy Mansion. His books of poetry—in particular 1974’s Where the Sidewalk Ends—are widely recognized as classics of children’s literature. But of course, like all the best works of art for children, adults can find much within for themselves. Here’s one of my favorites, including Silverstein’s original illustration:

Naomi Shihab Nye

Like Silverstein, Naomi Shihab Nye does a little bit of everything—she writes poems for both adults and children, picture books, short stories and YA novels, as well as songs. In Contemporary Women Poets, poet Paul Christensen noted that she “is building a reputation . . . as the voice of childhood in America, the voice of the girl at the age of daring exploration.” A fitting description for a poet who is the daughter of an American mother and a father who was a Palestinian refugee, who consistently represents both strands of her heritage and the ways they intertwine.

In 2012, Nye was named laureate of the 2013 NSK Neustadt Prize for Children’s Literature. In her nominating statement, juror Ibtisam Barakat wrote that “Naomi’s incandescent humanity and voice can change the world, or someone’s world, by taking a position not one word less beautiful than an exquisite poem…Naomi’s poetry masterfully blends music, images, colors, languages, and insights into poems that ache like a shore pacing in ebb and flow, expecting the arrival of meaning.”

Here’s a poem from A Maze Me: Poems for Girls, entitled “Mystery”:

When I was two

I said to my mother

I don’t like you, but I like you.

She laughed a long time.

I will spend the rest of my life

trying to figure this out.

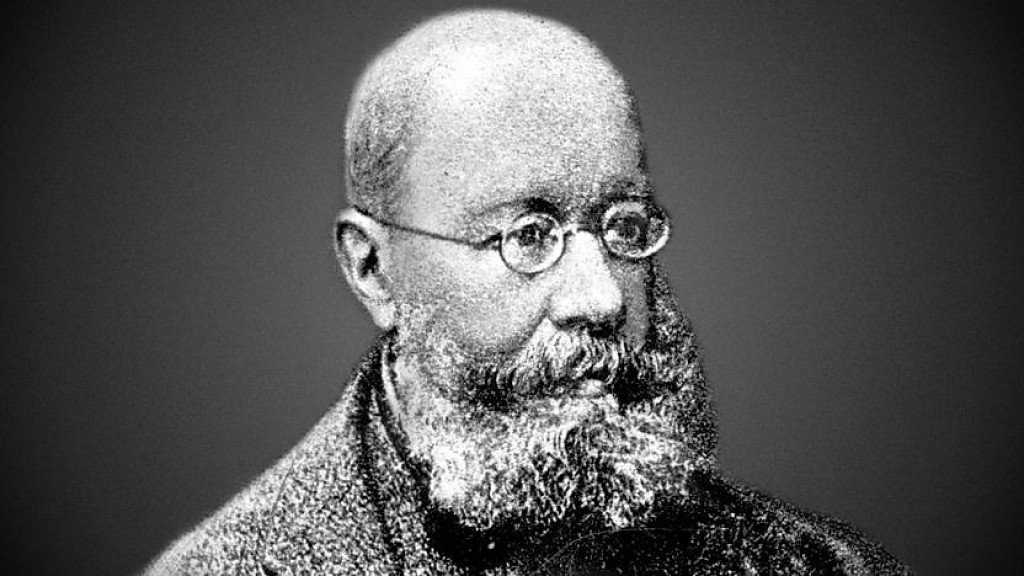

Edward Lear

I suppose now is the time that I should give up telling you how each one of these children’s poets was actually excellent in a variety of fields—it seems to be one of the things they have universally in common. Like Silverstein, Lear often illustrated his own poems. But Lear was also an accomplished wildlife illustrator, whom David Attenborough called “probably the best ornithological illustrator that ever was,” and a composer who was known for the works of Tennyson he set to music.

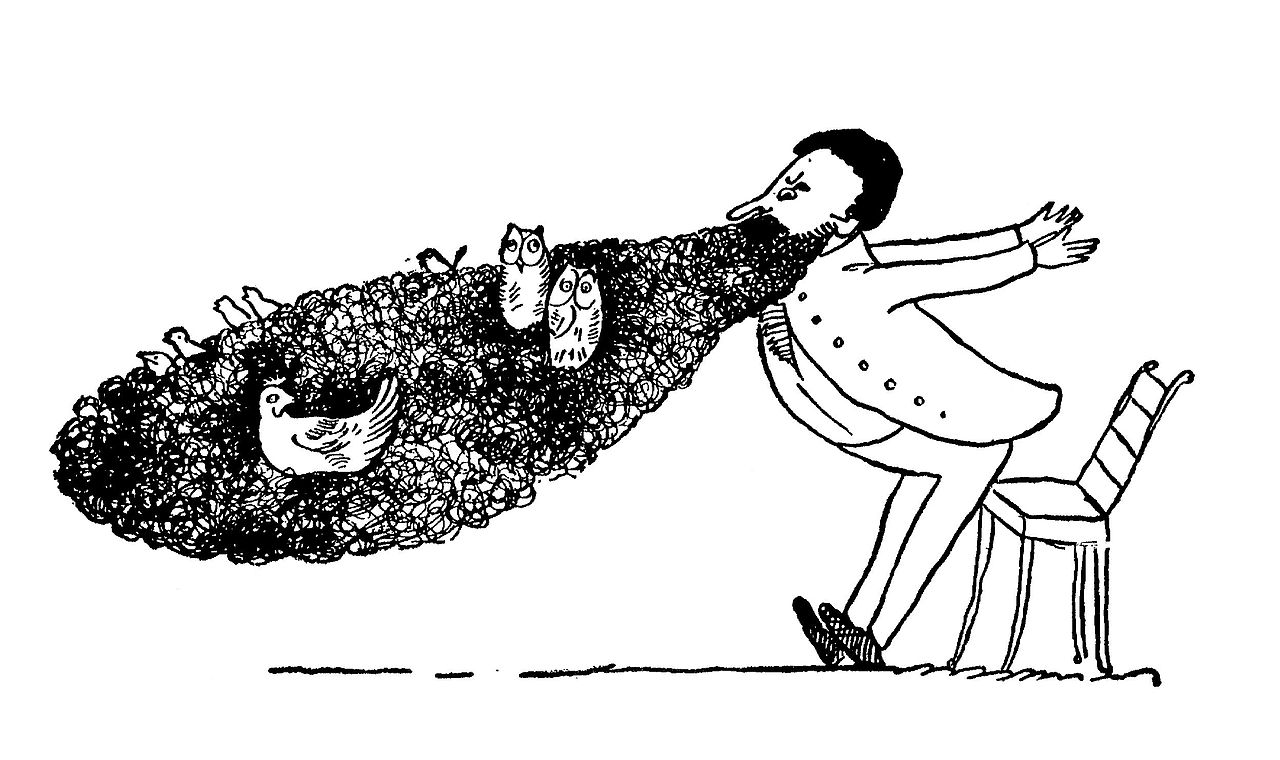

But more importantly for the purposes of this list, Lear is more or less the reason you and all of your friends know about limericks. In 1846, Lear put literary nonsense on the map with A Book of Nonsense—with three follow-up volumes—and is one of the most famous purveyors of absurd poetry and luscious neologisms. And as Poetry puts it, “the limerick protagonists provided for the didactically surfeited Victorian child examples of bizarre, misbehaving adults, with no blatant moralizing attached.” Two charmers from A Book of Nonsense are below, but find many more here:

There was an Old Man with a beard,

Who said, ‘It is just as I feared!

Two Owls and a Hen,

Four Larks and a Wren,

Have all built their nests in my beard!’

There was a Young Lady of Clare,

Who was sadly pursued by a bear;

When she found she was tired,

She abruptly expired,

That unfortunate Lady of Clare.

Francisco X. Alarcón

Alarcón decided to begin writing poems for children in the 1990s, when he “became aware that there were almost no books of bilingual poems children written by any Latino poet in the United States,” and decided to write his own collection, entitled Laughing Tomatoes and Other Spring Poems. Alarcón’s poems for children are minimalist and airy, and often presented in bilingual editions—having been raised in both the US and Mexico, he wrote in English, Spanish and Nahuatl, and he described himself as a “binational, bicultural, and a bilingual writer.” He also taught poetry to children, and said that “children from the third grade to the sixth grade are truly excellent natural poets,” which seems irrefutably true. Here’s his “Ode to My Shoes” from the collection Bellybutton of the Moon:

my shoes

rest

all night

under my bed

tired

they stretch

and loosen

their laces

wide open

they fall asleep

and dream

of walking

they revisit

the places

they went to

during the day

and wake up

cheerful

relaxed

so soft

Jacqueline Woodson

The highly-lauded Woodson is a contemporary master of children’s literature, probably most famous for her young adult novels, but skilled in writing for children, adolescents, and adults. Her two most recent works of literature for children are narratives in verse, including Brown Girl Dreaming, a memoir-in-verse that won the National Book Award for young people’s literature in 2014. She’s currently finishing up a two-year term as the Poetry Foundation’s young people’s poet laureate—in an interview at the time of her appointment, she said:

I think one thing I want to do as young people’s poet laureate is make sure all people know that poetry is a party everyone is invited to. I think many people believe and want others to believe that poetry is for the precious, entitled, educated few. And that’s just not true. Our children’s first words are poems—poems we and our listeners are delighted to hear and eager to understand. Rap is poetry. Spoken word is poetry. Poetry lives in our everyday. I’ve read some of the most poetic tweets, listened to poetic voice messages and snippets of dialogue between teenagers.

To which I have to say: four more years. Here’s a poem from Brown Girl Dreaming, entitled “Reading”:

I am not my sister.

Words from the books curl around each other

make little sense

until

I read them again

and again, the story

settling into memory. Too slow

the teacher says.

Read faster.

Too babyish, the teacher says.

Read older.

But I don’t want to read faster or older or

any way else that might

make the story disappear too quickly

from where it’s settling

inside my brain,

slowly becoming

a part of me.

A story I will remember

long after I’ve read it for the second,

third, tenth,

hundredth time.

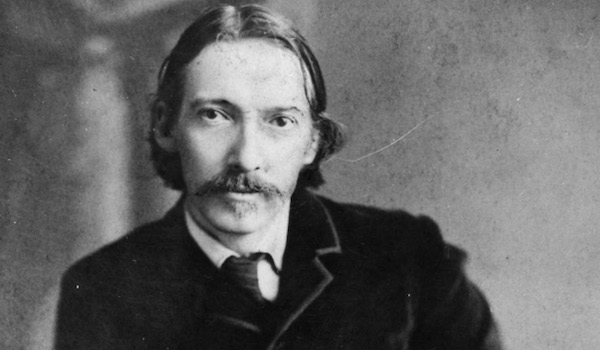

Robert Louis Stevenson

Perhaps you have heard of Robert Louis Stevenson, the author of classics like Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde>? Well, he also wrote a much-beloved 1885 collection of poems for children entitled A Child’s Garden of Verses, that has gone through countless editions and hands. Some argue that the darkness in some of the poems is reflective of Stevenson’s sickly childhood. Here’s a classic from the collection, entitled “My Shadow”:

I have a little shadow that goes in and out with me,

And what can be the use of him is more than I can see.

He is very, very like me from the heels up to the head;

And I see him jump before me, when I jump into my bed.

The funniest thing about him is the way he likes to grow—

Not at all like proper children, which is always very slow;

For he sometimes shoots up taller like an india-rubber ball,

And he sometimes goes so little that there’s none of him at all.

He hasn’t got a notion of how children ought to play,

And can only make a fool of me in every sort of way.

He stays so close behind me, he’s a coward you can see;

I’d think shame to stick to nursie as that shadow sticks to me!

One morning, very early, before the sun was up,

I rose and found the shining dew on every buttercup;

But my lazy little shadow, like an arrant sleepy-head,

Had stayed at home behind me and was fast asleep in bed.

Nikki Giovanni

The highly prolific Giovanni came to prominence in the ’60s as part of the Black Arts Movement and remains one of our most important American poets. (She’s also written picture books and essay collections.) All of her work directly addresses the African American experience, making her voice a particularly vital one in children’s literature. She published her first book of poetry for children, Spin a Soft Black Song, in 1971, and 2008’s Hip Hop Speaks to Children: A Celebration of Poetry with a Beat, which included a CD of poetry performances, was a New York Times bestseller. From her poem “Ego-tripping” (read the rest here):

I was born in the congo

I walked to the fertile crescent and built

the sphinx

I designed a pyramid so tough that a star

that only glows every one hundred years falls

into the center giving divine perfect light

I am bad

I sat on the throne

drinking nectar with allah

I got hot and sent an ice age to europe

to cool my thirst

My oldest daughter is nefertiti

the tears from my birth pains

created the nile

I am a beautiful woman

I gazed on the forest and burned

out the sahara desert

with a packet of goat’s meat

and a change of clothes

I crossed it in two hours

I am a gazelle so swift

so swift you can’t catch me

Paul Fleischman

Fleischman is yet another highly prolific writer who has published is almost every category you can name—novels, picture books, YA, short stories, nonfiction, plays—but he is best known for his collection Joyful Noise: Poems for Two Voices, which won the 1989 Newbery Medal. The book is a classic because it—rather unusually—invites cooperation in its own consumption, having been written expressly to be read aloud by two people, in part to reflect the “booming/boisterous/joyful noise” of insects, on which these poems focus. For instance:

Judith Viorst

You probably know Viorst as the author of Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, and of course she is, but she is also the author of a pair of delightful books of “poems for children and their parents”: If I Were in Charge of the World and Other Worries and Sad Underwear and Other Complications. I mean really, the titles alone—not to mention the wisdoms for kids of all ages:

If I were in charge of the world

I’d cancel oatmeal,

Monday mornings,

Allergy shots, and also Sara Steinberg.

If I were in charge of the world

There’d be brighter nights lights,

Healthier hamsters, and

Basketball baskets forty eight inches lower.

If I were in charge of the world

You wouldn’t have lonely.

You wouldn’t have clean.

You wouldn’t have bedtimes.

Or “Don’t punch your sister.”

You wouldn’t even have sisters.

If I were in charge of the world

A chocolate sundae with whipped cream and nuts would be a vegetable

All 007 movies would be G,

And a person who sometimes forgot to brush,

And sometimes forgot to flush,

Would still be allowed to be

In charge of the world.

Roald Dahl

Well, of course. The weirdo king of kiddie lit also wrote and published poems, including his famous Revolting Rhymes, a collection of six fairy-tale retellings in verse form. Only they’re not straightforward retellings, of course. Much like Anne Sexton (and much unlike her), he has his own ideas about how these tales should be told. For instance, this section, from “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”:

For ten whole years the silly Queen

Repeated this absurd routine

Then suddenly, one awful day

She heard the Magic Mirror say

“From now on Queen, you’re number two

Snow-White is prettier than you.”

The Queen went absolutely wild

She yelled, “I’m going to scrag that child.”

“I’ll cook her flaming goose, I’ll skin her

I’ll have her rotten guts for dinner.”

She called the Huntsman to her study

She shouted at him, “Listen, buddy,

You drag that filthy girl outside

And see you take her for a ride

Thereafter slit her ribs apart

And bring me back her bleeding heart.”

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.