10 Books to Read by Living Women (Instead of These 10 by Dead Men)

a) It's Women's History Month b) They're Better c) Avoid the Male Glance

Are you tired of the same old reading recommendations of books by Old White Men—so Old, in fact, that they’re Dead? I have an easy solution for you: read something else instead. I can even tell you what you should read instead—something that will scratch the very same itch but, importantly, be written by a woman, who is alive. Now, just to be clear, I’m not saying you should never read the below books by dead white men, or any books by dead white men, ever. Actually, almost all of the classics I’ve listed here are great. But for one thing, you’ve probably already read them. For another, their authors no longer have a shot at any royalties, being dead and all. Lastly, the books by living women I recommend instead are, if not necessarily better (though some are definitely better, if you can shake off your male glance), just as worthy of your time. So if this competition gets you down, I recommend you simply read both, and consider them a pairing, like very old wine and farm fresh cheese.

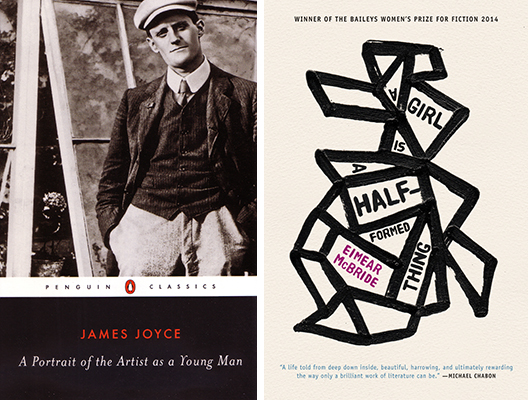

Instead of: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce

Read: A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing, Eimear McBride

Almost every reviewer who covered this novel has compared it to Joyce. Well, they have good reason. “When I began writing there was no real plan and nothing, I thought, that I urgently wished to say,” McBride wrote in The Guardian. “All I had was an idea about a girl walking down a London street over a single day and the feeling that Joyce’s observation—”One great part of every human existence is passed in a state which cannot be rendered sensible by the use of wideawake language, cutanddry grammar and goahead plot”—pointed somewhere interesting. So I wrote it on a scrap of paper, stuck it over my desk and began.” Joyce is referring to Finnegans Wake there, but as Annie Galvin pointed out in the LARB, McBride’s novel is closest to “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which similarly begins in babyhood and charts the maturation of a young mind as it strays from a stifling childhood home toward the more promising horizons of university and urban life.” Which doesn’t even get into the language—feverish, fragmented, flexible—and the style, an extravagant, difficult and ultimately compelling stream-of-consciousness. To this reader, A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing, though, is ultimately more enjoyable.

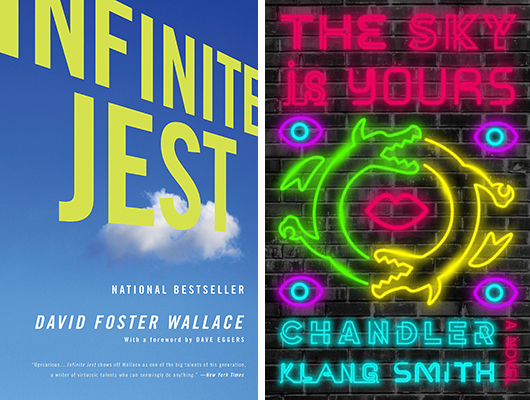

Instead of: Infinite Jest, David Foster Wallace

Read: The Sky is Yours, Chandler Klang Smith

Full disclosure: I read The Sky is Yours because of Leah Schnelbach’s review, which begins this way: “There have been a lot of books heralded as heirs to Infinite Jest, but I can happily say: this is it. I’ve found it.” Well, I thought, I like Infinite Jest and also I like dragons, so this should be a winner. It was. To be fair, it’s not really like David Foster Wallace’s behemoth. For one thing, Wallace was a lot of things, but he was very rarely silly. This book is sometimes silly. I kept putting it down, thinking that I wouldn’t pick it up again, because it was so ridiculous. And then I kept picking it up, and giggling to myself.

So: don’t read The Sky is Yours if you’re just looking for a book to be pretentious about. That said, I do ultimately agree with Schnelbach that this is a worthy heir to Infinite Jest. Both novels are fat, both are set in the future (though Smith’s future is further afield than Wallace’s), both take on our media consumption directly, both bristle with details and storylines. As Schnelbach points out, The Sky is Yours has is at least one allusion to Infinite Jest. But most importantly of all: as Wallace did in Infinite Jest, in The Sky is Yours Smith has invented the language she needs to tell her story. This is a book that invents itself.

Also, they both have three names.

Instead of: Oblomov, Ivan Goncharov

Read: My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Ottessa Moshfegh

What would you get if you took Oblomov—that 19th-century icon of upper-middle-class sloth, indecisiveness, and superfluity, who doesn’t get out of bed for the first 150 pages of his eponymous novel—and transported him to early-2000s New York City? Maybe someone like the narrator of Moshfegh’s excellent forthcoming novel, an independently wealthy young woman who wants nothing more than to sleep all the time, and will use any cocktail of drugs necessary to get herself there. There are critiques of excess, class and society in both of these novels, but the main point of interest in each is the luxurious over-indulgence of the main character, a coziness that becomes a compulsion. Oblomov is a classic, but My Year of Rest and Relaxation is much more fun.

Instead of: Dune, Frank Herbert

Read: The Broken Earth Trilogy, N. K. Jemisin

To be fair, Jemisin’s Broken Earth Trilogy (The Fifth Season, The Obelisk Gate, The Stone Sky) doesn’t feel particularly similar to Frank Herbert’s Dune series while you’re reading it. But Dune was one of the first popular speculative novels to take ecology, climate change, and the earth’s systems as a subject—and Jemisin’s novels are among the most recent (and best) to do so. (Neither, in case you’re wondering, is at all didactic about it.) But on a more essential level than that, I’ll declare this: Dune was the fantasy novel everyone should have been reading 50 years ago, and The Fifth Season is the fantasy novel that everyone should be reading now.

Instead of: A Sport and a Pastime, James Salter

Read: The Virgins, Pamela Erens

It’s not because both books are sexy (though both books are sexy). The formal conceit of Salter’s classic novel is that it is the story of an intense affair (in France, in the 60s) partially observed, but mostly imagined, by an obsessive third party. The Virgins is formatted in the same way, though Erens actually strikes closer to the heart by making all the players teenagers in high school—this being the time when it was usual (or more usual, at least) to obsess about one another’s bedroom activities. Erens herself has pointed to Salter as the inspiration for this narrative structure. In an interview with Tin House, she said:

I am an enormous Salter fan and I had read his story collections and his novels A Sport and a Pastime and Light Years. The Oates article reminded me of the setup of A Sport and a Pastime—a male narrator tells the story of a romance in which he doesn’t take part. That narrator describes encounters and events he couldn’t possibly have been a witness to. Suddenly I knew that was what I wanted to do with my own novel.

All I can say is: I knew it.

Instead of: Moby-Dick, Herman Melville

Read: The Vegetarian, Han Kang

Speaking of obsession: exchange an overlong and often-tedious novel where a man is obsessed with an elusive external white whale for a slim, electric one about a woman who is obsessed with an elusive internal “white whale.” Whereas the former leads to self-destruction, the latter leads to . . . well, self-destruction, but self-destruction that is also (for Yeong-hye at least) a triumphant seizing of agency.

Instead of: Winesburg, Ohio, Sherwood Anderson

Read: The Beggar Maid, Alice Munro

Winesburg, Ohio is the ur-novel-in-stories, set in a fictional small town (in Ohio, shocker), but The Beggar Maid is as good if not better: centering on the residents of another small town (this time in Ontario), in particular two women, Flo and Rose. (See also: Olive Kitteridge, by Elizabeth Strout, and pretty much everything else Munro has ever written).

Instead of: The Sound and the Fury, William Faulkner

Read: Sing, Unburied, Sing, Jesmyn Ward

“Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it,” Faulkner said in his Nobel Prize speech. “There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat. Like McBride with Joyce, Ward once printed out Faulkner’s speech and pinned excerpts above her writing desk. Now, with every book Ward writes, she solidifies her place as the contemporary bard of Mississippi, stepping into Faulkner’s admittedly large literary shoes. Her work is very different, but it is as much of the place as Faulkner’s, and is often told in multiple voices, suffuse with ghosts and songs and long family histories that hang around long after the family members themselves have gone to dust.

Instead of: Wittgenstein’s Mistress, David Markson

Read: Why Did I Ever, Mary Robison

Markson’s cerebral, fragmented text—ostensibly written by a woman who may or may not be the last human left on earth—is fantastic, and brilliant, and inventive in a way I wish I could find more often in novels. But so is Mary Robison’s Why Did I Ever, and it has the added benefit of being extremely funny. (See also: Dept. of Speculation, by Jenny Offill, and—though it’s a bit different—Jamie Quatro’s recent Fire Sermon, both of which are fragmented, incendiary, and truly wonderful.)

Instead of: The Catcher in the Rye, J. D. Salinger

Read: The Bluest Eye, Toni Morrison

As classic coming-of-age stories go, Morrison’s is simply better—and much more relevant to contemporary readers.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.