10 Books for Taylor Swift’s 10 Eras

Surprising Pairings from Swiftie Authors in the Know

For nearly two decades, Taylor Swift has gifted us with music for every moment and feeling. There’s the heartbreak and angst she’s most famous for, but true Swifties also know the joy, ambition, wisdom, rage, sincerity, humor, obsession, growth, sense of possibility, and resilience throughout her ten-album discography (not to mention the re-records with tracks from the vault).

A truly magical part of being a Swiftie, especially these days, is the communal appreciation of her work, so I asked 10 Swiftie authors if they would each choose one of her albums—also referred to as eras—and recommend a book to match. Their selections span centuries, from the mid-1800s to 2023. Some of the connections between books and albums are immediately apparent, while others are quieter. These more surprising pairings go beyond plot and character similarities and into tone, emotion, vibes, and the authors’ personal memories.

So many of these authors came of age alongside Swift and have the stories to prove it. I, too, remember where I first listened to each album: sashaying across my college campus to Speak Now, driving through the canyons of Los Angeles in my mid-20s blasting 1989, taking walks alone in the woods (appropriately) in my early 30s, a few months after the pandemic outbreak, humming folklore. You will see in these responses not only the way Swift’s music has changed and developed, but the way we have all grown with it—with her—as people, writers, and readers.

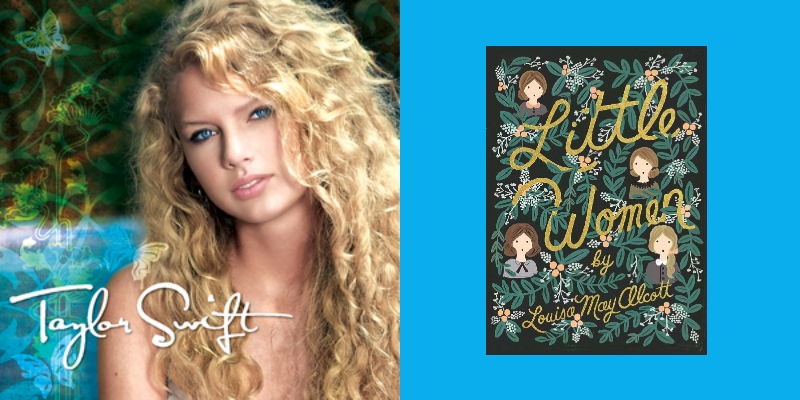

TAYLOR SWIFT: Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

Chosen by Umang Kalra, author of fig

I think I was nine when I first read Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, and then maybe 12 when I watched it come to life on a crackly television screen, suddenly possessed with the need to sell my hair and save my family from fictional financial ruin, to be proposed to with desperation that I did not yet know how to even properly imagine, to write and write and write and have that be my life.

I’m not sure how old I was when I first heard (or rather absorbed by osmosis) Taylor Swift’s debut album, Taylor Swift. I remember being huddled around a screen in the computer room at a friend’s house, watching Taylor’s blonde ringlets and startling features as she danced around fire and screamed that she really really hates that stupid old pickup truck she wasn’t allowed to drive! The rest, of course, is history.

Both Taylor Swift and Little Women live in my head as memories of disjointed attempts at being way more grown up than I had any business being. On some level, both of these works are about children trying to be older in fantastical, misguided ways—ways that make the grownups laugh a bit, whether it’s Mrs. March being so fully entertained by the girls’ plays or it’s us, now, looking back at our younger selves sobbing to songs like “Teardrops on My Guitar” and “Invisible.” There is so much idealism in childishness, so much pristine, untouched ambition for a perfect world: “Wouldn’t it be fun if all the castles in the air which we make could come true, and we could live in them?” asks Jo, while everyone around her is slightly amused by her seemingly deluded optimism. Taylor, more than a century later, feeling the same kind of complicated, prismatic love and having nowhere to put it, seems to agree: “We could be a beautiful miracle, unbelievable.”

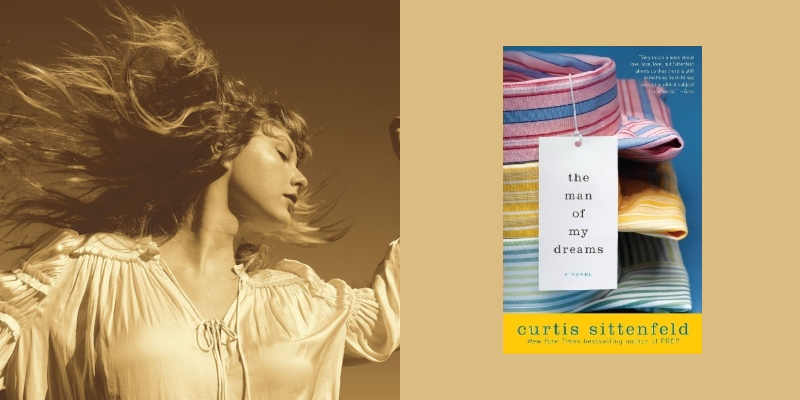

FEARLESS: The Man of My Dreams by Curtis Sittenfeld

Chosen by Caitlin Barasch, author of A Novel Obsession

I was an angsty teenager when I first listened to Fearless. It was 2008, and at 15 years old, I had just experienced my very first kiss with a boy I’d met on vacation who, regrettably, lived three thousand miles away. I spent that winter bereft and dreaming of California, where he lived, from the depths of a dark, cold November in New York. (Even remembering that period of my life, and its accompanying soundtrack, makes my prose angstier.) As we sent each other flirty messages on AOL Instant Messenger, “Fifteen” played on repeat: “‘Cause when you’re fifteen / Somebody tells you they love you / You’re gonna believe them / And when you’re fifteen / And your first kiss makes your head spin around / But in your life you’ll do things / Greater than dating the boy on the football team / But I didn’t know it at fifteen.”

Another queen of adolescent angst? Curtis Sittenfeld. Her second novel, The Man of My Dreams, follows a teenager named Hannah as she slowly, painfully grows up to realize the “man of her dreams” is a fiction. Sittenfeld’s deadpan humor and savage social observations, which manage to simultaneously honor and vilify the urge to obsess over boys who don’t deserve us, offers the same knowing wink and nod to a triumphant future as Taylor Swift provides in “Fifteen,” and also in “White Horse” with the lyrics: “‘Cause I’m not your princess, this ain’t our fairytale / I’m gonna find someone someday who might actually treat me well / This is a big world, that was a small town / There in my rear view mirror disappearing now.” I can even picture Hannah pretending to listen to Swift’s album ironically, while secretly feeling incredibly seen and validated by it!

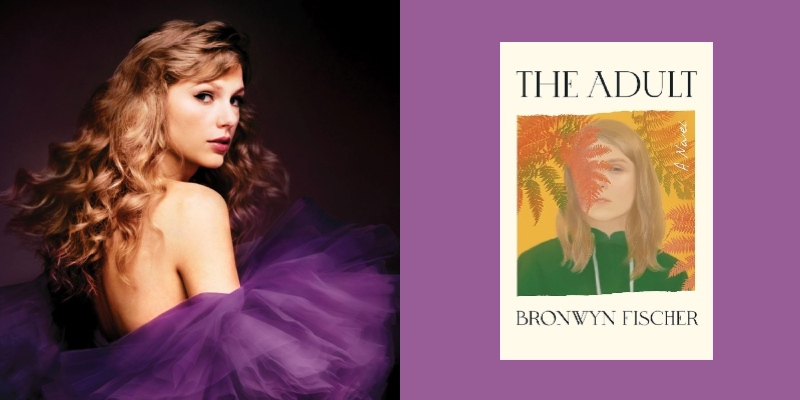

SPEAK NOW: The Adult by Bronwyn Fisher

Chosen by Marissa Higgins, author of A Good Happy Girl

Speak Now is the literary new adult of Taylor Swift’s albums, the emotional and lyrical little sister to Red, and eventually, evermore. Smart, moody, and sincere, Speak Now is a command, an imperative. Just tell me. Just set me free. Just rescue me. Writing this album between ages 18 and 20, Swift apparently suffered the same disarming vulnerability that swept not-famous high school grads across the country. Some, like Bronwyn Fischer’s protagonist, Natalie, find themselves living the future Swift describes in “Mean,” a PG fuck you to the townies: “Someday, I’ll be living in a big old city, and all you’re ever gonna be is mean.” For Natalie, the tender college freshman at the heart of Fischer’s debut novel, The Adult, the big old city is Toronto.

Natalie meets Nora, a lesbian in her thirties, by chance at a park near her college campus. The sheer serendipity of the meeting is amplified for shy, insecure Natalie because Nora expresses so much interest in her. “Who was I,” Natalie wonders, “If she was curious about me? Not the person I’d expected myself to be.” That sentiment fits all too well (sorry) with the unfortunately familiar age-gap power dynamics of “Dear John,” and the subsequent big emotions (even returning a text is not without an internal hero’s journey for Fisher’s lesbians) are in spirit with the pleading “come on, come on, don’t leave me like this, I thought I had you figured out” of “Haunted.”

Speak Now embodies the singular focus of loving someone we want to define us; if Natalie wants anything, it’s for Nora to consume her whole and spit her back out, fully formed, as the perfect partner. Both works are claustrophobic, healing returns to the years we spent making other people our identities.

RED: Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

Chosen by Laura Sims, author of How Can I Help You

It may seem like an odd pairing at first: Emily Bronte and Taylor Swift? But bear with me. Though its setting is late winter, I first read Wuthering Heights in autumn; now the season always brings to mind those stormy, shrouded moors, the backdrop to Heathcliff and Catherine’s exquisitely tormented love. I often find myself listening to Kate Bush keening the lines to her “Wuthering Heights” around that time… and similarly, the season draws me to Taylor Swift’s Red. Though it’s true that some key tracks are set in autumn, it’s more the album’s autumnal tone—like the novel’s—that stirs me: both works glow with an intensity of emotion like the last burst of color in the trees, and both brim with longing for what’s lost or in the past.

I can hear Heathcliff, post-Catherine, in the lines of “All Too Well,” a by turns mournful and fierce breakup ballad, singing, “Time won’t fly, it’s like I’m paralyzed by it;” and I hear Catherine, in spectral form, telling Heathcliff, “I’ll follow you, follow you home,” in “Treacherous.” I hear her again in “The Last Time,” singing, “Found myself at your door / Just like all those times before.” But it may be the title track, “Red,” that best expresses the synchronicity between these two works separated by hundreds of years. Everything has a color: the blue of “losing him,” the dark gray of “missing him,” but most of all, “loving him was red / Oh, red / Burning red.”

It’s true that the album and novel couldn’t come from more disparate worlds; you won’t find the class conflict, crippling illness, and frequent premature deaths of the 1800s in Red, just as you won’t see signs of our contemporary urban landscape or hear strains of pop music’s ferocious positivity in Wuthering Heights. But it’s their shared core that matters, one that holds obsessive, troubled love, haunted and haunting lovers, and, most of all, the “burning red” of all-consuming feeling.

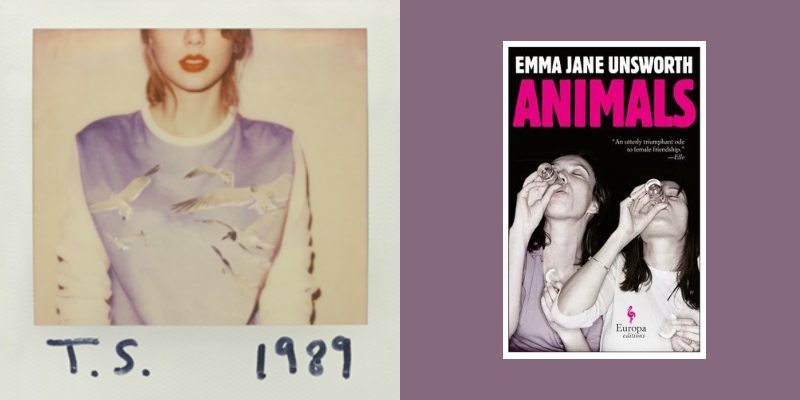

1989: Animals by Emma Jane Unsworth

Chosen by Gina Chung, author of Sea Change

Released in 2014, 1989 marked Taylor Swift’s official crossover from country-pop star to pop star juggernaut. As a fellow Sagittarius born during that momentous year, I was instantly seduced by the big, juicy synth hooks and supercharged anthems of 1989. While reviews of the time noted that the album seemed to take a more lighthearted, arch tone to love and relationships (who can forget the brilliance of “But I’ve got a blank space, baby / And I’ll write your name”), the album is also full of softer emotional moments, including “Clean,” a gentle yet searing ballad about healing and moving on from a toxic, addictive relationship. 1989 is, for me, Taylor’s coming-of-age album, with many of the songs charting the awkward, exhilarating, and sometimes painful process of growing up.

1989 pairs brilliantly with the darkly hilarious and incredibly visceral Animals by Emma Jane Unsworth (which coincidentally was also published in 2014). Animals is about a codependent friendship between two young women—a bit like Broad City if it were set in London and a whole lot darker. Protagonist Laura is a flailing call center worker and aspiring writer, and for the last ten years, she’s been best friends with Tyler, an American whose wealth and easy, entitled charisma scaffold their hard-partying social life. But at 32, Laura finds herself engaged to the more stable Jim, a classical pianist who wants her to give up drinking and disapproves of her friendship with Tyler. Pulled between Tyler and Jim, Laura has to decide for herself what kind of future she wants and who she wants to become.

In between, there are lots of hijinks, dick jokes, meditations on drug and alcohol use, and memorable lines like “Was I, as I had long suspected, one part optimism two parts masochism, like all the best cocktails?” (Which could also describe how I feel about the emotional highs and lows of 1989.) And while I won’t spoil the ending of the book, let’s just say that “Clean” being the closer on the standard edition of 1989 is appropriate for the way Laura’s story unfolds, in more ways than one.

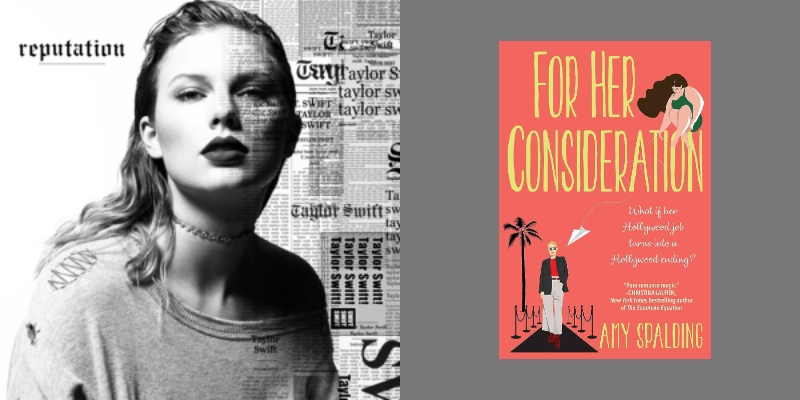

REPUTATION: For Her Consideration by Amy Spalding

Chosen by Pyae Moe Thet War, author of You’ve Changed

For Her Consideration by Amy Spalding swept me off my feet with its electric blend of Hollywood glamor, wonderful, dynamic characters that you want to grab brunch with, and a heavy dose of good old fashioned swoon. The story follows Nina Rice who, after a devastating breakup several years prior, has put up capital-W Walls around her heart, living on her own in the suburbs and focusing on her talent agency job. Enter Ari Fox, a young up-and-coming actress whose email account Nina is tasked with managing. Feelings emerge, and so on and so forth, until they fall for each other hard.

I’ve always loved Reputation because it sounds precisely like it was written by someone who was falling in real, true love (RIP Jaylor) after a period of fully believing that it just wasn’t for them—which is exactly what Nina does. When I hear Reputation lyrics like “Do the girls back home touch you like I do?” or “Is this the end of all the endings? / My broken bones are mending / With all these nights we’re spending” or “I’ll be there if you’re the toast of the town, babe / Or if you strike out and you’re crawling home,” I immediately picture Nina listening to this album on repeat in bed at night while daydreaming about Ari. And Ari’s point of view, that of a celebrity who is hesitant to bring a partner unfamiliar with the pitfalls of Hollywood fame into the spotlight, overlaps with songs like “Delicate” and “New Year’s Day.” Finally, although it goes without further explanation: “Dress” (IYKYK).

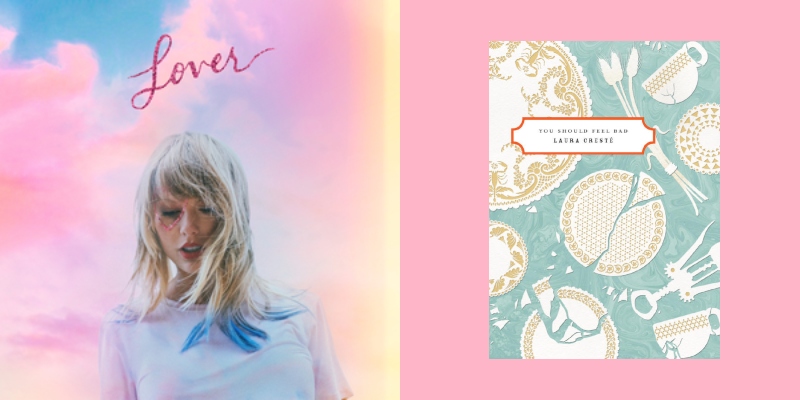

LOVER: You Should Feel Bad by Laura Cresté

Chosen by Kate Doyle, author of I Meant It Once

Lover is one of my favorite albums, and I turn to You Should Feel Bad—Laura Cresté’s poetry chapbook—for the same tender humor, biting intelligence, and wisdom wrung from one’s early twenties. Take, for example, Cresté’s poem “Mike.” The mid-twenties narrator finds herself in love with someone kinder than her past boyfriends, and we get this wry, sweet moment: “The way he loves me: wakes me with egg sandwiches / and says hey that poem / you wrote about your ex / is really good.” It’s a similar energy to the catchy jubilance of Lover’s “Paper Rings,” an upbeat track that goes rifling through good memories and laughs off fleeting arguments in a relationship that’s surprised both parties: “I hate accidents / Except when we went from friends to this.”

These unexpected moments we couldn’t have imagined when we were just a little younger is what Lover is all about: after the adolescent hope and longing of the early Taylor eras, after the break-up-shake-it-off-big-city energy of 1989, after whatever happened on Reputation, the Lover era is an entry into the greater complications of adulthood, but also its sweeter possibilities. There’s the romance of shared domesticity (“Lover”) and the sobering first experience of a loved one’s illness (“Soon You’ll Get Better”). There’s finally naming some bullshit you were too uncertain to speak of before now (“The Man”) and letting yourself be outright snarky where it’s called for (“I Forgot That You Existed”).

Cresté’s chapbook gets to the heart of these same difficulties and delights, the necessities and possibilities of early adulthood. In “A Fox’s Wedding,” she gives us this beautiful moment among friends, a life made for oneself: “Gemini birthday for Mike on the roof, overlooking the river. / Scraped-dry cheese plate and salad bowls, ice cream sandwiches / melting vanilla down our wrists, in the late-day light / that makes everyone beautiful.” Yet in the wider world, everything is broken: there’s the specter of climate change, there’s news of a woman randomly attacked in New Jersey. Meanwhile on Lover’s track “The Man,” rage seeps in around the album’s moments of joy. It’s so much easier to be a man: “When everyone believes you / What’s that like?” Or, as Cresté writes, “Women apologize for accidental touches— / pocketbook swinging widely, hand sliding down the subway pole. / A chorus of sorrys. Maybe it’s weak, but I love it / when we’re careful, because the world is not careful with us.”

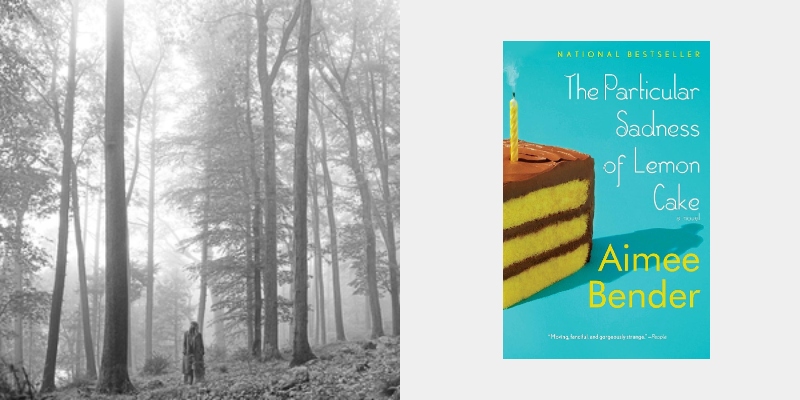

FOLKLORE: The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake by Aimee Bender

Chosen by Samantha Fain and Téa Franco, editors of Kiss Your Darlings: A Taylor Swift Anthology

When Taylor Swift wrote folklore, Aimee Bender’s novel, The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake, must have been on the top of her Pinterest inspo board. As Rose, the protagonist, bites into a slice of her homemade birthday cake, she realizes she has developed a mysterious ability: she can taste her mother’s emotions within it, and the flavor is frighteningly hollow. Fearful of her discovery and its consequences, Rose goes on a journey to understand her family’s emotions: their origins, their impact, and her place within their tangle.

We noticed the similarities between Bender and Swift’s writing immediately in this narrative. Bender matches folklore’s lyrical precision through her own lyrical prose, with sentences like “you get so used to the subtleties of beige and then a sunshine-yellow poppy bursts from the arm of a prickly pear.” Both authors’ rich imagery and metaphor bring the growing pains of girlhood alive, making the audience want to lay on the floor and cry. Just as the characters in folklore feel melancholic, isolated, and overwhelmed, Rose feels a similar grief as she navigates her ability to feel her family’s pain without fully understanding the reasoning behind their pain. An outsider in her own story, she interprets every detail of her life into a remedy for her family’s conflict. Rose is a bit of a mirrorball herself when it comes to her relationship with her family, or, as she says, “I was with them for all of it, but more like an echo than a participant.”

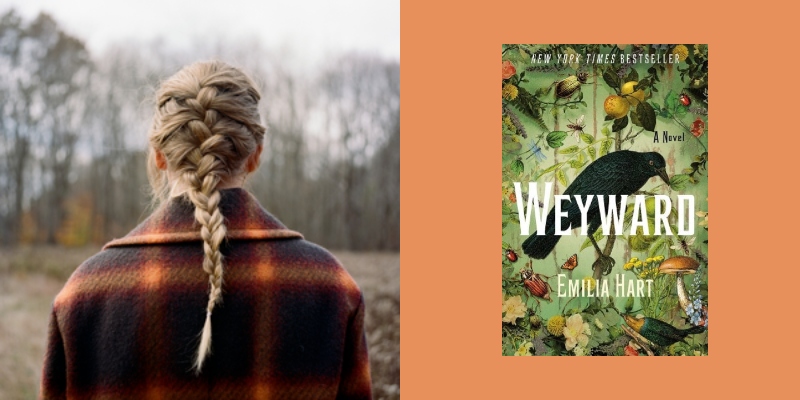

EVERMORE: Weyward by Emilia Hart

Chosen by Jinwoo Chong, author of Flux

It’s impossible not to group the evermore era, Taylor’s ninth studio album, with its sister project, folklore; both were released in the same year, marked a stylistic tangent from the radio pop of Lover, and ended just as quickly with the dawn of the Midnights era shortly after. But that’s how best to describe evermore: contained, self-sufficient, a respite within Taylor’s larger body of work that relies on previously underrepresented themes in her music: magic, fidelity, the allure and soul of the natural world.

Emilia Hart’s Weyward feels at home in this kind of world. The novel follows the stories of three women centuries apart in 2019, 1619, and 1942, who each learn a form of resilience and agency among secrets, madness, murder, and war. The aesthetics are fine-tuned and pitch perfect: ancient woods, crumbling manors and cottages, and powerful witchcraft. And still, both the album and novel contain a kind of grief, patched over and scarred but still there, nurtured and weathered by women who go elsewhere to heal, to the woods.

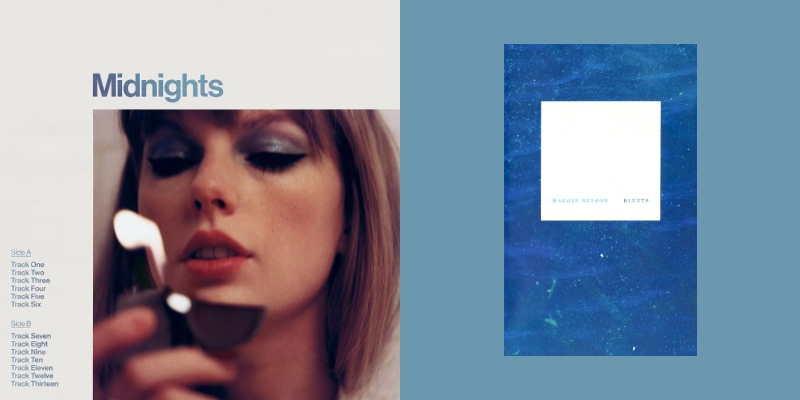

MIDNIGHTS: Bluets by Maggie Nelson

Chosen by Alisson Wood, author of Being Lolita

Taylor Swift introduced Midnights to the world as a sonic uncoiling around “the stories of 13 sleepless nights,” a reflective project at its core. The cohesion of Midnights both in its aural “vibe” and dark narrative focus brought me straight to Bluets by Maggie Nelson, a similarly circling project—part memoir, part essay, part poem—around the color blue. (Dare I say that midnight is a shade of blue?) Both hold a similar subject in their crosshairs: love, or the loss of it, and how color can shape an understanding of grief. The internet has suggested that Swift might have synesthesia, a blending of the senses. Bluets is in many ways an exercise in synesthesia, merging color with philosophy, art, and the personal. Nelson writes: “What I know: when I met you, a blue rush began.” And Swift, in “Snow on the Beach”: “This scene feels like what I once saw on a screen / I searched ‘aurora borealis green’ / I’ve never seen someone lit from within.” This tight blend of emotion and color bleeds through, leaving traces of intimacy everywhere.

These writers feel the pressure to produce even in the midst of personal loss: In Bluets, Nelson writes, “‘I just don’t feel like you’re trying hard enough,’ one friend says to me. How can I tell her that not trying has become the whole point, the whole plan? That is to say, I have been trying to go limp in the face of my heartache.” Swift similarly recounts in “Sweet Nothing,” “And the voices that implore, ‘You should be doing more’ / To you, I can admit that I’m just too soft for all of it.” While these expectations are rooted in familiar capitalism, we see a vulnerability among these works that is new.

Further, Nelson and Swift trace similar fears in their works, even the anxiety around having anxiety, writing lines that are a gentle fuck you to the expectation of emotional perfection. Nelson asks, “But why bother with diagnoses at all, if a diagnosis is but a restatement of the problem?” and Swift echoing in “Anti-Hero”: “It’s me, hi / I’m the problem, it’s me.”

Bluets and Midnights stand as stunning examples of their respective genres—voices that are somehow moody and luscious, cutting and bloody, soft and sharp. When Swift sings “Talk your talk and go viral / I just need this love spiral” in “Lavender Haze,” it’s only pop speak for Maggie Nelson’s lyrical prose: “This is how much I miss you talking. This is the deepest blue, talking, talking, always talking to you.” Each medium tells an intensely personal story, overlapping and splitting and coming back together, which transforms memory and emotion into something that can be swallowed whole by another person. Midnights and Bluets prove that art-making is a kind of magic.

Samantha Paige Rosen

Samantha Paige Rosen’s nonfiction has appeared in Slate, Electric Literature, Catapult, Washington Post, BOMB, Literary Hub, and elsewhere, and she has written short stories for Necessary Fiction and Lumina Journal. She earned an MFA in creative nonfiction from Sarah Lawrence College and is a proud Smith College graduate. Sam writes, tutors, and coaches writing outside of Philadelphia with her three cats. Say hi at samanthapaigerosen.com or on social: Instagram @samanthapaigerosen, Twitter @samanthaprosen.