We need to talk.

I’m writing to you so you’ll understand why I can’t write to you any more.

I could never talk to you. We didn’t exactly have a meaningful relationship. Perhaps that’s why I have all these words left when so many others have none at all. The postal system’s still going so I expect you will get this letter. Bills continue to be sent by mail (figures accompany icons: an electric light bulb, a gas flame, a wave for water) as do postcards (wordless views). And letters do still arrive so I’ll take this opportunity to get my words in edgeways while I can, folded into a slim envelope. When they drop through your letterbox, I hope that they don’t fall flat.

It’s the old story: It’s not you, it’s me. Or, rather, it’s the place we’re at. We don’t talk any more, not now, not round here. You know how things have changed. But I have to tell you all over again because what happened between us seemed to be part of what happened everywhere. It’s never useful to lay the blame but I do feel somehow responsible.

It was more than a language barrier. We were reading from the same page, at least that’s what I thought, but it was really only you that ever had a way with words. Sometimes you put them into my mouth, then you took them right out again. You never minced them, made anything easier to swallow, and the words you put in for me were hardly ever good. They left a bitter taste. As for mine, you twisted my words and broke my English until I was only as good as my word: good for nothing, or for saying nothing. I stopped answering and that was the way you liked it. You told me you preferred your women quiet. You studied the small ads: INCREASE YOUR WORD POWER! Trouble was, you didn’t know your own strength.

Communication went out of fashion about the same time as we stopped speaking. It started, as does almost everything, as a trend. Early adapters, seeking something retro as usual, looked to their grannies, their aunties: silent women in cardigans who never went out. Who knows if these women were really quiet? Whether their adoption of these women’s silence was a misinterpretation of the past or a genuine unearthing, it happened. Initially gatherings—I mean parties, that sort of thing—became quieter, then entirely noiseless. Losing their raison d’être, they grew smaller and eventually ceased to exist altogether in favour of activities like staying in, waiting in hallways at telephone tables for calls that never came.

We scarcely noticed how the silence went mainstream but if I have to trace a pattern I’d say our nouns faded first. In everyday speech the grocery store became ‘that place over there’; your house, ‘the building one block from the corner, count two along.’ A little later this morphed into, ‘that place a little way from the bit where you go round, then a bit further on’. We began to revel in indirectness. Urban coolhunters would show off, limiting themselves to ‘that over there,’ and finally would do no more than grunt and jerk a thumb. They looked like they had something better to do than engage in casual conversation. We provincials were dumbstruck.

Grammar went second. We tried abbreviations, acronyms, but they made us blue, reminded us of the things we used to say. Not being a literary nation, we’d never quite got our heads around metaphor, and our frequent grammatical errors were only one thing less to lose. We said ‘kinda’ a lot, and ‘sort of’ but, y’know. . . We lost heart and failed to end sentences.

We have no sayings, now, only doings, though never a ‘doing word’. Actions speak louder than words (a wise saw: if only I’d looked before I ever listened to you), especially as we can’t remember very far back. We have erased all tenses except the present, though for a while we hung on to the imperfect, which suggested that things were going on as they always had done, and would continue thus.

At least schooling is easier now there are only numbers and images—and shapes, their dimensions, their colours. We don’t have to name them: we feel their forms and put them into our hearts, our minds, or whatever that space is, abandoned by language. We trace the shapes of the countries on school globes with our fingertips. And they all feel like tin.

Being ostensibly silent, for a while social media was still a valid form of communication, though touch-keyboards began to be preferred to those with keys. On websites, people posted photos of silent activities, as well as those involving white noise—drilling, vacuuming, using the washing machine—during which communication could patently not take place. Some questioned, in the comments boxes below, whether these photos might be staged but doubts were put to rest when the majority began to frown even on the use of writing. Some of us wondered whether internet forums could have themselves been the final straw: the way we’d wanted what we said to be noticed and, at the same time, to remain anon: the way we’d let our words float free, detach from our speech acts, become at once our avatars and our armour.

Trad media was something else. The first to go ‘non-talk’ were high-end cultural programmes: those ‘discussing’ movies and books. Popular shows featuring, say, cooking, gardening, home improvement, and talent contests, relied on sign language and were frowned upon by purists. On highbrow broadcasts, critics’ reactions were inferred from their facial expressions by a silent studio audience. Viewers smiled or frowned in response but their demeanours remained subtle, convoluted, suited to the subjects’ complexities. Fashions in presenters changed. Smooth-faced women were sacked in favour of craggy hags whose visual emotional range was more elastic. As all news is bad news, jowly, dewlapped broadcasters with doleful eyebags drew the fattest pay packets. This was considered important even on the radio.

There were no more letters to the editors of newspapers. There was no Op to the Ed, then no Ed, but newspapers continued to exist. Their pages looked at first as they had under censorship when, instead of the offending article, there appeared a photograph of a donkey. But, after a period of glorious photography, images also departed and the papers reverted to virgin. Oddly, perhaps, the number and page extent of sections remained the same. People still bought their daily at the kiosk; men still slept under them in parks. Traditions were preserved without the clamour of print. It was so much nicer that way.

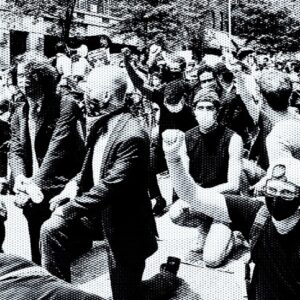

Not everyone agreed. There were protests, often by unemployed journalists and photographers, but these were mostly silent: we had internalised the impoliteness of noise and were no longer willing to howl slogans. The personal being the political, this extended to domestic life. Fewer violent quarrels were reported. With no way to take things forward, relationships tended to the one-note. Couples who got on badly glared in mutual balefulness; the feelings of those in love were reflected in one another’s eyes.

If, at an international level, there was no news, at a local level there was no gossip, so most of us felt better. We ceased to judge people, having no common standards. The first wordless president fought her (his? its? As we could no longer name it, gender scarcely mattered any more) campaign on a quiet platform, gaze fixed on the distant horizon. He (she? it?) knew how to play the new silence. The opposition, opting to fill the space left by speech with random actions, was nowhere. A more liberal, thoughtful community emerged. Or so some of us believed. How could we tell? Of course there were conspiracy theories. Old folks have always complained that a man’s word isn’t worth as much as it used to be, that promises nowadays are ten a penny, but radical economists charted a steep devaluation. Once, they proposed, you could have had a conversation word for word, though a picture had always been worth a thousand. That was the system: we knew where we stood, and it was by our words, but the currency went into free fall: a picture to five thousand, ten thousand words, a million! Despite new coinages, soon it was impossible to exchange a word with anyone, unless you traded in the black market of filthy language. And, if you did, there was always the danger you’d be caught on street corners, unable to pay your respects.

Some clung to individual words to fill the gaps as language crumbled but, without sentence structure, they presented as insane, like a homeless man who once lived on the corner of my block and carried round a piece of pipe saying, ‘Where’s this fit? Where’s this fit?’ to everyone he met. Except that the word-offerers didn’t even form phrases, they just held out each single syllable aggressively, aggrievedly, or hopefully.

As for the rest of us, words still visited sometimes: spork, ostrich, windjammer. . . We wondered where they had come from, what to do with them. Were they a curse or a blessing? We’d pick them up where they dropped, like ravens’ bread on soggy ground.

Of course the big brands panicked, employed marketeers to look into whether we had ever had the right words in the first place. Naturally, we never read the results of their research. The new government launched a scheme (no need for secrecy as there’s no gossip). Bespoke words were designed along lines dictated by various linguistic systems, and tested. As someone who, until recently, had lived by her words (if there are words to live by: as you know, I actually live by the church), I was involved or, perhaps, committed. Under scientific conditions, we exchanged conversations involving satch, ileflower, liisdoktora. We cooed over the new words, nested them, hoping meaning would come and take roost, but meaning never did.

A scattering of the more successful words was put into circulation and, for a while, we tried to popularise them by using them at every opportunity. Despite sponsored ‘word placement’ in the movies (which were no longer talkies), the new words slipped off the screen: our eyes glazed over. The problem, as it always had been in our country, was one of individualism. By this stage no one expected words to facilitate communication. The experiment resulted not in a common language, but in pockets of parallel neologisms. Being able to name our own things to ourselves gave us comfort. I suspect some people still silently practice this, though of course I cannot tell. I have a feeling their numbers are declining. Even I have stopped. It proved too difficult to keep a bag of words in my head for personal use and to have to reach down into its corners for terms that didn’t come out very often. They grew musty. Frankly it was unhygienic.

It was sad to see the last of the signs coming down, but it was also liberating. In the shop that was no longer called COFFEE, you couldn’t ask for a coffee any more, but that was OK. You could point, and the coffee tasted better, being only ‘that’ and not the same thing as everyone else had. It was never the same as the guy behind you’s coffee, or the coffee belonging to the guy in front of you. No one had a better cup than you, or a worse. For the first time, whatever it was, was your particular experience and yours alone. The removal of publicly visible words accelerated. Shop windows were smashed, libraries were burned. We may have got carried away. As the number of billboards and street signs dwindled, we realised we had been reading way too much into everything. What did we do with the space in our minds that was constantly processing what we read? Well. . . I guess we processed other things, but what they were, we could no longer say.

Some of us suspected that new things had begun to arrive, things there had never been names for. They caused irritation, as a new word does to an old person, but because there was nothing to call these new things, there was no way to point them out or even to say that they hadn’t been there before. People either accommodated them or didn’t. We’re still not sure whether these things continue to live with us, or if we imagined them all along.

__________________________________

From WORLDS FROM THE WORD’S END. Used with permission of And Other Stories. Copyright © 2017 by Joanna Walsh.