When the Editor Becomes the Writer

Logistics, imagination, and anxiety of working on both sides of a book

Perhaps we all have one question we get asked repeatedly. Mine is always the same question. How do you do it? How do I hold a demanding job as an executive editor at a major publishing company while also maintaining an active writing life? The answer is sometimes a mystery even to me. There are challenges to wearing two hats. Am I an editor and a closet writer, or am I foremost a writer and a closet editor? Full confession. I am both. One enterprise could not exist without the other. They fuel each other in inexplicable ways. They are two sides of the same coin.

Here are the logistics. I like to write in the morning, first thing when I wake up. I love the ritual of showering, getting dressed and brewing a pot of coffee. Art needs its own private sanctuary in which to be made and I’ve created a sort of temple in my dining room where I have a tray with pencils and eraser and notebooks at the ready to be pulled out. I like those few hours in the morning before my day has begun where I can slip into my imaginative life almost like a thief. This life is connected to my emotional and psychic world and that is where my art comes from. I have always thought of writing as its own secret language, or to be more precise, its own second language that exists in tandem to the language of the day to day. I take mine early before the emails, phone calls, and to-do list demand my attention. Writing is an obsessive enterprise. Even when we think we’ve abandoned our characters for the day they work themselves in our consciousness. Sometimes I think of a phrase or comment one of my characters might say when I’m pumping the Stairmaster at the gym. Sometimes I’m on the subway and I take out my iPhone and make a note to myself. I’ve been known on deadline to review galleys before the sun shines, write first drafts on notepads and store them in the fridge in case of a fire. Writing is like solving a puzzle. At the end of the day, or more precisely, nearing the end of the project–you want to make sure all the pieces fit. I had the pleasure of hearing Richard Ford speak this summer at conference and he said, in response to the idea that novels are never fully finished, only abandoned, that the author must authorize their work. I like that phrasing.

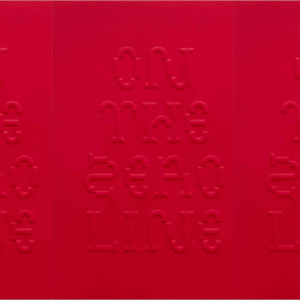

When I am working on a novel and bringing characters to life I am projecting my own vision, arguments, dissatisfactions and quandaries into them, almost as if I were Mary Shelley creating Frankenstein. I don’t know how they will act or how they will face a certain situation unless I put them in it. I like when my characters do what they are not supposed to do. I like when they get ornery and subversive and act out their erotic and psychological impulses. My new novel, The Prize, about a gallerist at a small Manhattan art gallery, is to a certain extent about how our work life defines and shapes us. It began with a question. What would happen when an artist he makes famous turns on him? Would he recover, be vindicated, fall under feelings of failure? Character is usually built in the bad times not the good times so I decided to stake the odds up against my guy and see how he would fare and what I might learn from it. It was kind of awful because I am basically a moral person and when two of my characters show their worst sides I feel the pain with them. Writing is pain in a writer’s need to make her sentences behave and also in the way in which she must live through the quarrels, missteps and trails with her characters. What happens when a person has not fully grieved a loved one? How does that impact his life? How important is it that our spouse know everything about us? Is infidelity irrecoverable? Can a long marriage rejuvenate itself? What does artistic competition do to a marriage, fuel it or destroy it? The novel gave me a platform to investigate these questions and concerns.

What happens to my creative life, my wandering child, as I like to refer to her, during the day when I am at the office and later in the evenings when I read manuscripts for work? Somehow the unconscious is working there too. Before I go to sleep at night I sometimes think about what situation I’ve put my character in the night before and sometimes in the morning I have a solution. I’ve learned to trust this elusive process and not to worry about it too much. Characters are with you, even when you have abandoned them for the day.

So this gives you some idea of what consumes my imaginative life. What happens when my early morning hours have extinguished and it is time to go to the workplace where I earn a living? I shelve it completely. I find a great deal of freedom in letting go of the imaginative work and diving into the editorial work. The two enterprises are completely different. As a writer, I am serving my imagination. As an editor, I am serving the author’s imagination. Editing per se is not a creative act on the page. It is a response to creativity. An editor is good at puzzles, at seeing where a piece may belong and fit together. An editor is thoughtful and analytical; good at spotting holes in arguments and seeing through throat clearing and hand-waving to get to the heart of the matter. Most important, an editor must be a voracious reader. I got an M.A. from Johns Hopkins at the Writing Seminars and then an M.F.A at the University of Iowa Writer’s Workshop and for three years all I did was read, write and critique other student’s work. I read everything I could get my hands on in trying to develop my craft as a writer and I read like a writer. I read to see how it was done. I think these skills transferred well to the kinds of books I tend to edit, fiction, poetry and narrative non fiction.

An editor has a certain amount of knowledge developed over time about what kinds of books seem to work for his or her particular house, and for herself personally and those are the kinds of books the editor undertakes. A good editor is intuitive and relies on her intuition when reading a manuscript. Of course, it’s subjective and it takes confidence and a huge leap of faith to commit to any project but once the commitment is there the editor becomes possessed. There are many challenges to being an editor. Perhaps one of the most difficult is when an author turns in a manuscript that is not what the author imagined. My former editor-in- chief cautioned his editors when taking on projects not to write them or imagine them in our heads. Trust the author. Look at what’s on the page. That comment has stayed with me.

Aside from editing, editors are involved in titles, jacket design, positioning, writing catalog and jacket copy, all in collaboration with the author. The rest of the day transpires in meetings and answering emails, reviewing contracts or writing sales presentations or helping an author brainstorm ideas for publicity.

People often ask me if I need editing. They assume that because I am an editor I can edit myself. I crave a second reader, a close careful eye. I love to be edited in the way in which I edit and I have been lucky to find sensitive and intelligent editors for my own work. All writers need editors. When the tables are turned and I’m on the other side, waiting for my editor to send me the jacket for my book, or review catalog or jacket copy, I feel waves of anxiety rise in me that I know my own authors feel. I try and hold back and maintain my dignity but it’s hard. Suddenly I find that I am that author who doesn’t feel we’ve nailed the jacket and is suddenly sweating out those five or six weeks before the novel is about to come out when it can get weirdly quiet. I don’t like it. Have we hit the nail on the head in the copy? Will my book find readers? And like all my writers, I fret out those first prepublication reviews. An author I admire told me once that he never reads his reviews. He said if you believe the good ones than you have to believe the bad ones. I do not have that muscle in my psyche.

Sometimes I know too much about the things that can go wrong and wish I was a writer living in Montana or Cape Cod who knows very little about the process of how books get acquired, made and sold. I could write an entire book on the subject! Emily Dickinson famously said, “tell it slant,” and maybe, in my new novel, The Prize, a novel about the thorny marriage between art and commerce, I have chipped off a tip of that iceberg.

Jill Bialosky

Jill Bialosky is the author of four poetry collections: The Players; The End of Desire; Subterranenan, a finalist for the James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets; and Intruder, a finalist for the 2009 Paterson Poetry Prize. She coedited Wanting a Child and has written two novels, House Under Snow and The Life Room. She is also the author of the highly acclaimed New York Times bestseller History of A Suicide: My Sister’s Unfinished Life which was a finalist for the Ohioana Award and Books For Better Life Award. Her poems and essays have been published in many magazines including The New Yorker, The Nation,Redbook, O, The Oprah Magazine, Real Simple, Kenyon Review, Antioch Review, The New Republic, Paris Review, Poetry, and The American Poetry Review. She lives in New York City where she is an Executive Editor and Vice President at W.W.Norton. Learn more at www.jillbialosky.com.