What the WGA’s Historic Contract Means for All Writers in the Fight Against Generative AI

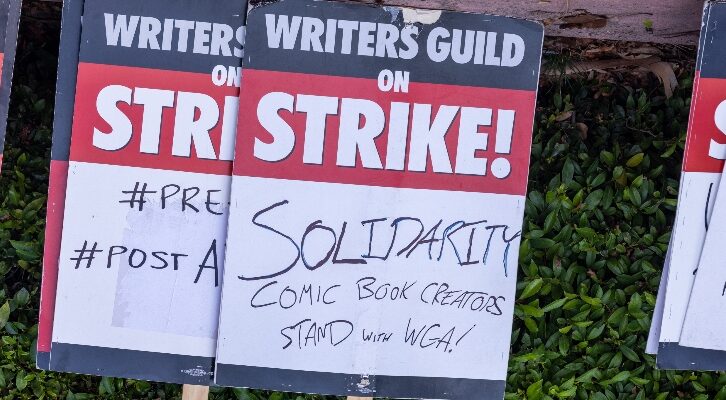

Alexis Gunderson on the Wins of Hollywood’s Hot Labor Summer

The funniest picket sign I saw during the Writers Guild of America’s 148-day long strike came on Pretty Little Liars day, way back in mid-June. It was in the hands of actress Troian Bellisario and it read: “AI would have had me calling the cops… Season One.”

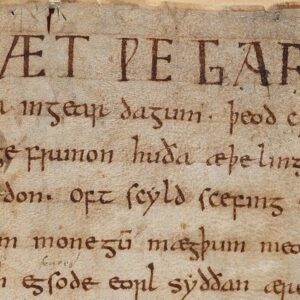

If you watched even a fraction of the show that made a clue-whistling parrot famous, you’ll get the joke immediately. Never mind how long it took Bellisario’s Spencer to call a single cop—this is a show that wrote a threat on a miniature scroll of parchment and stuffed it between an unconscious teen girl’s molars, sewed finger bones into the corset of a fashion show bridal gown, and turned (as a jape in the eleventh hour!) a whole side character into a cremation diamond. I don’t care how advanced generative AI technology might eventually get: you will never convince me that anything less than a room of deeply weird, deeply flawed human brains could come up with a show even half as gloriously unhinged.

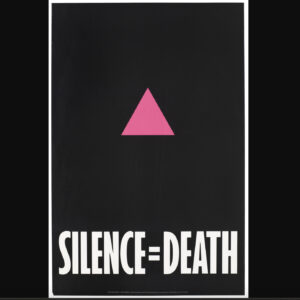

Stiil, apt as I found Belisario’s sign to be, the sanctity of human creativity wasn’t the main reason generative AI haunted the WGA picket lines all summer. As the studios’ dismissive out-of-hand rejection to the Guild’s initial set of contract proposals so sharply underscored, the specter of generative AI was on the picket lines for the same reason the writers were: the future and respect of the profession itself.

To that point, and to be crystal clear about the stakes in play here, this is what the WGA asked for during the original round of contract negotiation back in May: “Regulate use of artificial intelligence on MBA-covered projects: AI can’t write or rewrite literary material; can’t be used as source material; and MBA-covered material can’t be used to train AI.”

The studios rejected the proposal and “countered by offering annual meetings to discuss advancements in technology.”

Please note that less than two months after this laughable counter-proposal was made, GPT-4 was made available to the general public. A little over a month later, Gizmodo had fired its Gizmodo en Español staff and put an AI translator on their beat. Within more or less the same news cycle as the WGA’s memorandum of agreement was released, OpenAI pushed a splashy announcement that “ChatGPT can now see, hear, and speak.” And the studios were out here offering annual meetings! To simply discuss advancements in technology! Absolutely wild.

Wild and, perhaps unsurprisingly, galvanizing.

“[The studios’] response really did change the conversation,” Mr. Robot writer Ted Kupper said in a phone interview earlier this summer. “I think if they had come back with a reasonable compromise, that would have been one thing. Instead they were like, well, we’ll promise to talk about it. I mean, it was just fuck you, basically. And I think in a way that kind of showed their hand, because they’re not going to do that unless they’re already committed to using it, right?”

The specter of generative AI was on the picket lines for the same reason the writers were: the future and respect of the profession itself.

Trying to divine the concrete intentions of a group as diverse and arguably fractious as the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) is almost certainly a fool’s errand. Still, it’s not a stretch to see how lowering the overhead costs of human labor would be in the best (which is to say, most coldly profitable) interests of a publicly traded company—not least for the fact that Large Language Models, at least in the form they exist today, aren’t likely to mount their own collective labor action for fair labor conditions anytime soon.

That workers coming together in solidarity to show their collective power works is the exact point the WGA was making in the 148 days its members were out on strike, and that the still-striking SAG-AFTRA members are continuing to make. It’s also a point that was proven out by the WGA’s hard-won new deal that came out last week.

After 148 days of collective (human) action—not to mention multiple botched rounds of studio-planted rumors, and unwavering solidarity across the labor movement—this is what the writers won:

• AI-generated material can’t be considered literary or source material (e.g. intellectual property) under the MBA

• AI technology itself can’t be considered a writer under the MBA

• Studios must disclose to writers if and when any material they give writers has been generated, in part or in whole, by AI

• And writers themselves are allowed to use AI software (with studio consent and within relevant company policy) when performing writing services under the MBA

This is exciting for the WGA, absolutely. But it should also be electrifying for creative workers—and especially writers—across the board. Because of course it’s not just Hollywood writers who have reason to be wary of the effect that generative AI will have on written art, and it’s all too easy to see that, had the studios gotten their way and given AI-generated material a foot in the intellectual property door, the viability of any kind of creative writing as a sustainable career would have all but evaporated. As author and WGA writer Steph Cha noted when we spoke in May about authors standing in solidarity with their counterparts in Hollywood, writing is already an infamously precarious vocation. Paying the bills as a fiction writer, a journalist, a poet, a critic? Nearly impossible these days! And that’s without the threat of generative AI as a replacement for human bylines or a wrench in the works of the short story market.

This brings me to the last point I want to make, about an angle that has (so far) gotten slightly less mainstream coverage: the implication this victory has for similar fights being mounted against the threat of generative AI in other creative sectors.

Had the studios gotten their way and given AI-generated material a foot in the intellectual property door, the viability of any kind of creative writing as a sustainable career would have all but evaporated.

Or, maybe a better way to say it is, the implication this victory has for labor organizing as a critical point of leverage and power-building in those similar fights, both in spite and because of the lack of robust union structures in just about every part of the American creative landscape that isn’t Hollywood. Because while the last several months have seen a number of fiery open letters signed by artists against the general concept of generative AI, multiple (and increasingly splashy) lawsuits filed against specific generative AI developers, and several listening sessions and open comment periods from the US Copyright Office (not to mention an entire Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights from the Biden Administration), it’s Hollywood’s Hot Labor Summer that has gotten artists their first concrete protections against their creative labor being devalued and replaced by generative AI technology.

And crucially, they didn’t do it alone. Rather, they did it with a swell of solidarity from workers across not just Hollywood but the labor industry writ large. (Including, full disclosure, my own union home, the Freelance Solidarity Project, where I spent the summer working on various campaigns in solidarity with both striking Guilds.) This is a point that 2023 Negotiating Committee member Adam Conover came back to in a written response to a criticism from a listener of Matt Belloni’s The Town podcast after Conover appeared there for a guest spot:

The deal we won with our shared solidarity was NOT small; it was the largest deal we’ve won in decades, and triple the AMPTP’s pre-strike offer. But more important than the dollar value is the precedent our deal set for all workers. We got the companies to agree to deal terms that they swore they never would, and that means it will be easier for other unions, and other workers, to extract the same from them in the future. […] The fact is that a win by one group of workers is a win for all, because it widens the aperture of what the companies must allow. And that’s because workers, fundamentally, are on the same side.

(The full text of this response is included in the Friday edition of Belloni’s What I’m Hearing newsletter. Emphasis is Conover’s own.)

As a labor organizer also currently engaged in finding ways to tackle the incursion of generative AI into my profession, the WGA’s win—bolstered by the point Conover is making here about the strength creative workers have when we come together in solidarity—is sending me into that work with renewed vigor. The fight for just contract terms can and will be hard, but importantly, it is winnable.

Moreover, it’s a fight that isn’t going to go away—as Kupper, the Mr. Robot writer I spoke with earlier in the summer, noted when commending his fellow union members for approaching the question with as much common sense as they did.

“I was really happy to see what the union leadership proposed,” he said. “Because they could have been just trying to get rid of [AI], right? But they didn’t do that. They asked for some definitional protections to make sure that [the technology] is not going to replace humans directly, and that it’s not going to be used to circumvent some of the rules that [previous contracts] have already put in place.”

This felt like the right path to Kupper because, at the end of the day, AI is a powerful technology that’s only going to get more powerful as time goes on. (And to his point, has already gotten more powerful in the months since we last spoke.) And as powerful as it has the chance to be for executives, it can be just as powerful for writers.

“People are going to use the tool,” he explained. “So asking for a set of very common sense restrictions [allows] it to be like other technological tools we use to enhance our ability to create art—which, at the end of the day, is what I think these technologies ought to be for.”

And thanks to the WGA’s 148 days of collective action, the union now has that very promise in writing.

*

This piece was written after the 2023 WGA strike, but still during the 2023 SAG-AFTRA strike for a similarly just contract. Without the labor of the actors currently on strike, the scripts that WGA writers create wouldn’t make it to the screen.

Alexis Gunderson

Alexis Gunderson is a writer who left the academic world of Russian Literature to join the secular one of television and cultural criticism. Her work appears regularly at Paste Magazine, and has also been found at Birth.Movies.Death, Syfy Wire, and Screener TV. She lives in the DC area.