What It’s Like to Write Crime Fiction in the Era of Black Lives Matter

A Roundtable on Race, Bias, and Gun Control in America

This spring, we contacted three successful crime-fiction writers, Rachel Howzell Hall, Bill Loehfelm, and Henry Chang to have a conversation about race, law enforcement, and literature. Specifically, we asked them how the Black Lives Matter movement has altered their point of view as writers of color who regularly explore the interplay between the police and underprivileged communities. It took some time to make the scheduling work. The week we finally were able to set aside to have the conversation just so happened to be the week of the shootings of Philando Castile, Alton Sterling and the police officers at the protest in Dallas. This conversation is always relevant and always necessary, but suddenly it felt even more urgent. We hope the conversation that follows engenders more dialogue.

Rachel Howzell Hall: It’s interesting to talk about Black Lives Matter, but people were protesting before it had this name. I remember being in LA in the ‘80s and not driving through certain neighborhoods, because you’re not supposed to go through Beverly Hills or Pasadena or Glendale. When we went to see Do the Right Thing near UCLA, we came out after the movie and there were riot police, because they thought we were going to riot. So there’s always been this kind of weird, tenuous relationship with cops and trying to grow up and not have this jaded, cynical view toward law enforcement.

Bill Loehfelm: I saw somebody say something yesterday, that nothing is new about this except for the cameras—the omnipresent recording—but that this kind of behavior has been going on forever basically.

RHH: Yeah, nothing’s new except the eyes. Not the victims or their families, but Facebook. In a weird way, it feels like vindication, that people of color aren’t crazy or conspiracy theorists or that we overreact to everything. It’s like, “Here’s the video. What do you think is happening?”

BL: And now you’re watching white people twist themselves into knots to make the old explanations and the old reasoning work, but for the new reality that everybody can see now.

Henry Chang: Well, we were first approached to do this a month ago, but sadly we have much more to talk about today. You know, it’s never been if the next incident will happen; it’s been when. And that when has arrived the last couple days in Minnesota and Louisiana, and I think it’s time for people with good will and reason to have meaningful conversations about race in this country and about gun violence.

BL: It’s literally from one end of the country to the other. It’s from Baton Rouge to Minnesota to Staten Island, New York. It’s been from one side of the country to the other. It’s so clearly and obviously a national problem. I think you’re right, Henry, it’s time for people to start speaking out about it in every possible venue. There are a certain number of people whose minds are never going to change, and we simply need to outnumber them now.

RHH: So how do you do that through art, through what we do? Do you think people who already agree with us will read our work and just say “amen” and that’s it? What role do artists play in this entire thing?

Do you think people who already agree with us will read our work and just say “amen” and that’s it?

HC: When we were first approached, the question posed to us was “How does the black lives matter movement affect us as writers in terms of our point of view and in terms of stories we might write in the future?” My initial response was “It hasn’t changed my perspective much at all.” In all my books I talk about racism and the NYPD—and not just racism, but sexism as well. And now you have people who are targeting Muslims because of the things that have been going on. It’s just…it’s nothing new. It’s in all my books. It hasn’t changed my perspective. I’ve been sympathetic to the Black Lives Matter, I’ve marched, I’ve raised my hands, but I’m not a cop hater. And now you got that long hot summer we’ve all been talking about this year.

BL: I really agree with what Henry says: every argument is not a binary. It can be easy to fall into that binary thinking with social media, and I think politicians live on this way of thinking—but it’s not all us or them. You can support black lives matter and you can support your local police department. No reasonable person agrees with what happened in Dallas—or what happened in Baton Rouge or what happened in Minnesota or what happened in St. Louis. I think that’s the place where artists come in—we need to keep putting the complications back into the argument. You see in a lot of the cable news media and on social media that really half our political structure is perfectly okay with Americans hating each other. They depend on it. That needs to be called out. To me, one of the great (as in large, not as in good) legacies of the Bush/Cheney years is this fixation on the binary, us vs. them, good vs. evil, black vs. white. But as artists our job is to recomplicate things, to make sure we complicate our work with real people.

RHH: Yeah. With my series, my lady cop is from the neighborhood that she polices. There’s that video that was circulating yesterday of the female black cop from Cleveland who just goes off on the entire thing. Well, she’s not this power hungry, jack-booted bully that people tend to hate in cops. She is a caring person, a mother, a wife, who wants to do good for communities, and this is how she chooses to do it. That’s the cop I want to write about, and that’s who I want to be the hero. Because cops are not homogenous creatures, just as blacks and Asians and Latinos are not homogeneous people. And ultimately, you’re right, Bill, there’s no easy us vs. them, black vs. white—it’s all just one big mess that is America. It’s frustrating, because you want to point out all the nuances, but it’s more than just what one book can do. You need a whole series!

BL: And my series and your series and Henry’s series…they’re an ongoing complicated conversation that doesn’t devolve into shouting. I think you’re right: cops are not a homogenous group. There are no really homogenous groups. And so one group saying, “They’re all bad so they hate us,” doesn’t get you anywhere, no matter who’s pointing the finger.

HC: We need to get away from the labels and stereotypes and all the hate and all the anger to be able to sit down and have a reasonable conversation. Nobody knows the answer, but something’s gotta be done.

RHH: I mentioned Do the Right Thing earlier, and it’s a timeless picture because the same thing will be happening in Brooklyn or wherever in America in the summer this year, in just a week or so. It’s timeless, unfortunately.

BL: And one of the great things about that movie and that story is that it’s complicated. You kinda feel for everybody.

RHH: Yeah, you do. And I think, again: that’s a great place where books get to kind of take the time to sprawl out and tell the stories of those many people that populate everyday life.

HC: Yes, I think that’s finally happening. I think we’re starting to get more of our stories out now, now that we’ve gotten past #OscarsSoWhite. I don’t know how much difference that’s going to make, but it’s a beginning.

RHH: I think so, too.

HC: I’m waiting for more Asian-American stories to come out.

BL: I think part of what people find frustrating is minority groups have been fighting this battle for decades if not for centuries and because it’s so much more visible now there are so many people acting like it’s new. There are so many people who’ve never heard stories like this or saw videos like this or read articles about it or heard people speak on it. They’re like “Oh, why is this happening all of a sudden?” But it’s not. It’s frustrating. For so many people, this problem and this conversation has been going on for such a long time, but you have so many people walking into it being like, “2016 is just a bad year.” And you’re like, “Nooo. Think about ‘96, ‘86, ‘76, ‘66 going all the way back.”

RHH: And that’s why I kinda cock an eyebrow at Black Lives Matter, because we’ve always said that—it just didn’t have a hashtag. With King and Malcolm X and Sojourner Truth and on and on—hell, the Middle Passage—we’ve always said that. It just didn’t have a slogan, it just didn’t have the visibility that it now has. I went to UC Santa Cruz from ‘88 to ‘92, and when I got there, there were no such things as Ethnic Studies Classes. So we marched to get Ethnic Studies classes. We told the grocery store down the hill that we wanted Red Rooster hot sauce and more than a shelf of black hair care products. We fought to get those things, and by the time we graduated, we had those things. We didn’t call ourselves anything, it was just us, doing this one thing together with like-minded individuals. So black lives have always mattered—it just didn’t have a hashtag.

HC: You’re speaking from a place that you look too young to be speaking from.

RHH: Really?

HC: I remember Malcolm X’s funeral. I remember the Harlem riots. I remember fighting for Ethnic Studies at City College. You don’t look that old.

RHH: Well, that’s the sad thing, I was talking to my 12 year old daughter about this because she’s starting to understand some race things. I said, “Well, my brother, your Uncle Terry, was born in 1963 at a time when black folks couldn’t eat at a Woolworth’s counter.” This is our lifetime. The more things change, the more they stay the same, unfortunately. It’s such a cliche, but it’s a cliche for a reason.

BL: Henry, is it especially frustrating for you having already lived through the ‘60s? I heard someone say the other day that this is ‘68 all over again—especially with the political convention coming up. Do you feel like we’ve gotten anywhere? Do you feel like you’re spinning your wheels?

HC: It’s very frustrating. I come from a time when we had the Black Panthers, we had the Young Lords, we had the FALN [Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (English: “Armed Forces of National Liberation”)]. So this is really one big circle. It’s coming back around. It’s really sad, and I wanted to see what the message of Black Lives Matter is, and if the goal is to bring attention to all these unjust killings and just the indifference where they can kill unarmed people—

BL: Or legally armed people, or basically anyone they want!

HC: Yes, the last couple days have been a good example. If that’s the message of Black Lives Matter—to keep a focus on this and try to see that people get justice—that’s what I’m marching for. If it turns out unfortunately to inspire people who are on the fringe of the movement and have a lot of anger to come out and kill cops who have nothing to do with the racism and, you know, may be the greatest guys and the most just people in the world—if it does that, which it has, then I feel really frustrated. Because anybody who’s seen the Laquan McDonald video, and over here in New York we had Eric Garner being choked to death, and nobody’s being indicted—I just think there’s something wrong with that, that it’s inspiring people to do the wrong things.

BL: Part of what staggers me about it is the over and over zero to murder with these law enforcement officers. That to me points to systemic problem in the hiring process and the training process. How does this guy who can’t effect a traffic stop without killing somebody, how does he get to that point without somebody noticing? It makes me question: Is he trained? Is he monitored? Are people paying attention to these officers going through the process? It’s one after the other. And it’s always a misdemeanor. It’s a traffic stop. It’s selling cigarettes. It’s selling CD’s. It’s walking down the street in your hoodie with an iced tea—which is not even a misdemeanor, which is not even criminal. How does “Protect and Serve” become “Stop and Murder”? No process is perfect, but there’s supposed to be a process to make sure that people who can’t do the job don’t get the job.

How does “Protect and Serve” become “Stop and Murder”?

HC: I’m not surprised. Here in New York, the NYPD has over 30 thousand officers. Even if one percent of them are bad cops, we’ve got hundreds of bad cops out there. Most cops, I think, are good.

RHH: I agree.

HC: In Ferguson, they found out that a lot of cops over there were systemically not good, but most of these cops across the country are good. They put on their uniform and go to work. But if two or three percent of the cops are bad, that’s where you’ve got a problem.

BL: I think you’re right that in larger cities that can be a lot of cops. Two, three, or four percent can be a lot of armed and badged people out there who can’t do the job.

RHH: If that were a statistic for a plane crash, we wouldn’t accept that. If your chances of dying on a plane were that high, there would be no airline industry. But with human life here on the ground, it’s like, “Well, that’s not a lot of people, that’s not a lot of bad cops.”

BL: Also, who are the bad cops being bad to? Black and brown people. And if you’re not one, maybe you don’t worry so much about it, that they’ll come for you.

RHH: And that’s the other frustrating thing about the rest of the country not understanding the everyday fear that people of color have just going about life. Whenever my husband goes out to be with friends, game night, or has to work late, I’m like, “Please text me when you’re there, please text me when you’re on your way home, just be very very careful,” and then I pray. And that’s just my normal. One day, my 12 year old daughter will be going out with black boys in their daddies’ cars, so not only do I have to worry about her relationships with that boy—the regular parent things—but I have to worry that, hopefully, the boy won’t be in too nice of a car or else he’ll get stopped by the police and my daughter will be in the car with him. So I now have to worry about other people’s children. So it never stops. The burden is always on us to pray and hope and plan and warn, and I am exhausted. I am exhausted with it all.

BL: And that’s not free. That’s not equal

RHH: Not at all.

HC: From an Asian person driving a car here, I don’t have those same concerns. So it goes to your point, you know?

RHH: And I’m actually glad you don’t. It shouldn’t be. That is not a badge I want. I don’t want to be a part of that club. But alas, here we are…

HC: The sad thing is, for example, here in New York City, we have Stop and Frisk. When you have a program like that, you have a lot of cops out there stopping and frisking black people, and that’s part of their daily job, so they’re going to do their job many times and stop black people who look nothing like gangbangers, people going to work, gonna stop them. It got to be very oppressive. So what happens when awareness of this becomes evident? Then the police back off. I think we went from half a million Stop and Frisk down to like 60 thousand, something like that. So, clearly the cops are backing off, but what’s bad about that for black people, is that the cops are no longer doing their jobs. And the evidence of that is that six months after all the cops backed off, shootings went up because people are no longer afraid to carry their guns. So now there’s more shootings than there had been, and yet the NYPD is able to twist the statistics and say, “Well yeah, shootings are up, but homicides are down.”

BL: I had a cop tell me in New Orleans it’s bad aim. I’ve talked to some people in the NOPD for the series, and they say that part of the problem is that the kids carrying guns are younger and younger and they have less experience shooting and they have worse aim. And that’s why you have fewer homicides.

HC: And that’s why you have a lot of innocent people getting shot.

BL: And that’s why you have fourteen shell casings at a shooting now and bullets going through windows.

HC: That goes to the issue of gun violence and gun control. You hear a lot lately about, “Oh, we need to ban assault weapons, because of what happened in San Bernardino and what happened in Orlando, how are people getting these assault weapons.” But assault weapons account for actually very few of the homicides in this country. People are killing each other with handguns. You can’t fit an AK-47 in your pocket or your briefcase—that’s not what you are carrying in the projects.

BL: No, but you can fit them in the backseat of your car.

HC: Well, that’s what you do in a drive-by, but most people get killed with handguns. So how do we effect gun control? By limiting assault weapons?

BL: I think so, I think no American citizen needs an AR-15 or a semi-automatic. I don’t believe those guns should be available to the American public. I’m really sick and tired of waiting for when we get to the “well-regulated” part of the Second Amendment. Because those words are in there. I respect the Second Amendment. I grew up in the Northeast, but I’ve lived in Louisiana for a long time, and it’s a very gun-friendly state. I know people who hunt. I’m not saying nobody should have a gun, but it’s time to be reasonable. There are certain products in the gun industry that are designed for mass murder, that are designed to kill a lot of people in a closed space as quickly as possible. None of those products need to be available to the civilian public.

RHH: Because where does it stop? I know this is hyperbolic, but why not a rocket? Why not a tank? Why not all of the other things the army uses that we should not have?

HC: I think the guy in Orlando had hand grenades.

RHH: What the hell for? Why do you need hand grenades? How do you get hand grenades?

BL: The internet and gun shows. A big thing in the South is gun shows. Where they don’t have to perform background checks, where you don’t necessarily need ID, where I can buy something out of your truck in the parking lot.

RHH: Which just doesn’t make any sense. You can tell me what I have to do to my body, but someone can go get a gun without checking to see if they’re crazy or not. I don’t understand it. I really don’t understand it.

BL: There are lots of states in the South where it’s easier to buy a gun than it is to register to vote.

HC: Right. Well, we need to do something about that. I come from a neighborhood that was rife with gang conflict, the most violent times in Chinatown history here. Everybody had a gun. Myself included. And it was the easiest things to get. And you know how we got them? We saw some guys down South.

BL: There’s been a pipeline to the North and the West Coast from the Deep South since forever. That’s not the only problem, but it is a big problem in so many southern states. When I’m driving down the highway to see my wife’s people in Georgia and North Carolina, there are billboards for pawn shops: Electronics, Toys, CDs, Jewelry, Guns. And I’m like, “Guns shouldn’t be on that list!”

RHH: Like I said before, there are so many issues to write about. Mystery writers, like funeral directors, will never have to say, “Hmm, what shall I write about today?” My Evernote is full.

HC: I’m sure there’s a number of writers who are just ripping off the headlines and are writing their books right now, probably in January you’ll be reading them…

BL: I hope so, and I hope there are young writers of color coming up with their pens on fire.

RHH: Yeah, and there was actually an issue a few days ago, when Ben Winters’ book came out. The words “brave” and “daring” were used in that profile. I hope one day that people of color who’ve been writing about this stuff for years and years will one day get the TV deal and one day get the New York Times write-up and all the attention that white men have gotten for saying this.

BL: I’m at a thriller-writing conference right now, and it’s a topic of conversation. Some people have brought up that there’s a dearth of writers of color. At every level.

RHH: We’re a small little group.

BL: Not just a dearth of writers of color, but also agents of color, editors of color, publishers of color, TV producers of color.

HC: I’ve never been more aware, until recently, how pervasive that is in the publishing industry. When I first got published I was like, “Oh yeah! Cool, cool cool!” and I didn’t notice that there were no Asians in the room, no black people in the room.

BL: It’s viewed as this crazy liberal industry. It’s all art farts and hippies and art school people. And yet…

RHH: And yet. And yet. It’s exhausting. I wrote a piece last year about just how exhausting it is. I had just come back from Bouchercon [World Mystery Convention] in Long Beach, and it was just so emotionally taxing. I had to go to my room sometimes, and I would call my husband crying, because it’s just so much to listen to the success of others who are writing the story that you know first-hand. It’s not being a tourist. This is actually my world and my people and my struggle. You get the publishing deal, and you’re happy for that. I love my publisher. But what now? What next? It’s not like I want to be a kajillionaire or anything like that. But I’d like recognition. And I’m glad that this is a conversation. Even though the cynic in me says, “Ain’t nothing gonna be done.” Because here we are talking about something Henry has lived through before in the ‘60s with people of color trying to get their due process.

I had to go to my room sometimes, and I would call my husband crying, because it’s just so much to listen to the success of others who are writing the story that you know first-hand.

HC: It’s been a long road.

BL: Well, I guess the upside is that we haven’t stopped talking about it. And maybe each time we talk about the subject, more people get involved in the conversation and the voices get louder. Unfortunately, the right road isn’t a straight line. It’s a wave, there’s a push forward and a push back, a push forward and a push back. I guess you hope each wave pushes a little further along the beach, I guess.

HC: Well, I hope these changes come sooner rather than later, because I’m coming toward home.

BL: Well, I hope we all get to see these changes sooner rather than later.

RHH: I do, too.

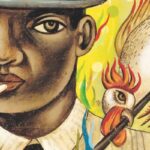

Featured image: still from Beyoncé’s video for “Formation.”