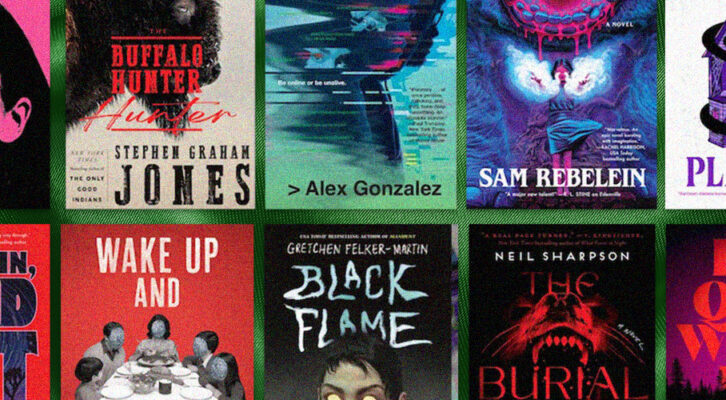

'What If You Get Pregnant? Would You Be Okay with That?'

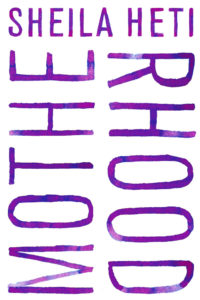

Read from Sheila Heti's New Novel, Motherhood

Yesterday, Erica, whose first baby is due any week now, sent me a painting by Berthe Morisot. She said, This painting reminds me of you. It’s what I think you’d look like if you had a child. I wrote her back saying that the woman in the painting looked a little bored, but she replied saying that the woman was interested in her sleeping baby, and felt I would be, too. I had interpreted the woman’s hand as having been placed on the edge of the bassinet kind of carelessly, without a thought. But Erica said she felt the hand was laid over the edge of the crib tenderly and protectively.

That does seem good—to lay your hand on reality. To move away from the distortions of your mind and feel what actually is.

*

This afternoon, I went to my doctor. She did a check-up, then asked me questions about my life, including what sort of contraception Miles and I were using. I grew embarrassed, admitting the truth: pulling out. It was what I had used with almost every man. What if you get pregnant? Would you be okay with that? I tried to answer in an easy way, but soon my sentences got twisted up. After the appointment, I walked in the streets and called Teresa.

I brought up my worries over paths not taken, and she said everyone had those, but often when you looked back on your life, you saw that the choices you made and the paths you went down were the right ones. She said it wasn’t a matter of choosing one life over another, but being sensitive to the life that wants to be lived through you. You need tension in order to create something—the sand in the pearl. She said my questioning and doubts were the sand. She said they were good and forced me to live with integrity, to interrogate what was important to me, and so to live the meaning of my life, rather than resort to convention.

Then to try and discover and live my values, even if it may not seem like I’m moving forward in my life, while my friends appear to be moving forward in theirs—ticking off all the boxes. Ask only whether you are living your values, not whether the boxes are ticked.

After our call, I realized the thing I always do: I try to imagine different futures for myself, what I would most like to occur. I don’t know why I do this, when any of the things I’ve hoped for—whenever I have actually got them—are nothing like what I imagined they’d be. Then why don’t I spend time acclimating myself to what actually occurred? Why not make peace with the way things are, given what I know about life from actually living? Instead I spin fantasies, when the only happiness I have ever known has occurred without my design.

*

Your idea about what your life is about, or should be like, occurs even before your life has had a chance to unfold. So much time that hasn’t had the opportunity to present itself, you spend in efforts trying to make the space ahead fill in exactly the way you hope it might. So what is the point in having that time? Of being in it at all? Why don’t you just die when a sufficiently pleasing idea about what your life ought to look like materializes in your mind?

The reason we don’t just kill ourselves when we have figured out what we want our lives to look like is because we actually want to experience things. But what happens when things we thought we wanted to experience don’t occur? Or when something we didn’t think we wanted to experience does? What’s the point in living all that other stuff, the stuff we never wanted, the stuff we didn’t choose?

Since life rarely accords to our expectations, why bother expecting anything at all? Wouldn’t it be better not to plan ahead? But that seems crazy, too, because planning and desiring sometimes works. Even if it doesn’t work, it still gets us somewhere. Or at least it seems like if we didn’t desire and plan, we’d be stuck in one place.

“Nobody completely expected it to go the way it went—their life. Nobody is completely happy with the way things turned out for them. But most people manage to find some pleasure in it anyway.”

It is often said that whether or not to have children is the biggest decision a person can make. That may be true, but it also doesn’t mean anything. A decision happens in the private mind of one. It is not an action. For things to happen in a life, other people must participate. You have to will it. Many things have to collaborate. Life itself has to will it. A decision in the mind is pretty small. It doesn’t make babies.

If a decision in the mind doesn’t make babies, why do I spend so much time thinking about it? We are judged by what happens to us as though our deciding made it happen. A lot of time is wasted in thinking about whether to have a child, when the thinking is such a small part of it, and when there is little enough time to think about things that actually bring meaning. Which are what?

Nobody completely expected it to go the way it went—their life. Nobody is completely happy with the way things turned out for them. But most people manage to find some pleasure in it anyway.

*

A friend of mine who was dating a man, quite early on in their fucking heard the sound and agreed to go ahead. She told him to come inside her. Then she got pregnant, and she chose to break up with him, but they remained friends. She found a boyfriend who she wanted to raise the child with, and the father takes the kid on weekends. They all love the boy and everything seems fine. What a way to live! To respond to the call and, once that’s done, make the practical decisions and make them well.

I also heard the sound last August, deeply in my soul. I never wanted a child as much as I did that month. I remember sitting on the lakeside dock of my friend’s mother’s cottage, telling her of my desire—but not telling Miles, for he had only started articling at a criminal defence firm a month before, and it didn’t seem fair to bring it up with him then. The timing wasn’t right. Nine months later, four of my friends gave birth. What was the sound we all heard that August?

*

When I was younger, I told myself that if I was ever going to have a child, it would only happen if I accidentally became pregnant. Well, I did accidentally become pregnant, and I decided not to keep it.

I was twenty-one at the time, and switching to the birth control pill. The moment I discovered I was pregnant, I decided I would have an abortion. There was no gap between finding out and knowing what I wanted to do.

The doctor who examined me advised me to keep the baby. He showed me the sonogram, even though I didn’t want to see it. He told me it was too early to get an abortion. Because it was possible that I could miscarry, he said it would be wrong to do it now. He joked that I should have the baby and give it to him; he said I could come over to his house with bags of milk every week. It wasn’t until I left his office that I realized what he meant: milk that would come from my breasts.

I spent the days before my next appointment doing nothing but waiting for my abortion—smoking pot, eating candies and chocolate and chips, drinking and smoking too much, as if to poison the little thing that was growing inside me, that was making me nauseous all day.

Only today, as I’m writing this, does it occur to me that he was lying; he wanted me to change my mind. You don’t have to wait for an abortion. But I was too young then, and too all alone, to see it.

*

Why are we still having children? Why was it important for that doctor that I did? A woman must have children because she must be occupied. When I think of all the people who want to forbid abortions, it seems it can only mean one thing—not that they want this new person in the world, but that they want that woman to be doing the work of child-rearing more than they want her to be doing anything else. There is something threatening about a woman who is not occupied with children. There is something at-loose-ends feeling about such a woman. What is she going to do instead? What sort of trouble will she make?

__________________________________

From Motherhood. Used with permission of Henry Holt and Co. Copyright © 2018 by Sheila Heti.

Sheila Heti

Sheila Heti is the author of eleven books, including the novels Pure Colour, Motherhood, and How Should a Person Be?, which New York deemed one of the “New Classics” of the twenty-first century. She was named one of the “New Vanguard” by the New York Times book critics, who, along with a dozen other magazines and newspapers, chose Motherhood as a top book of 2018. Her books have been translated into twenty-four languages. She lives in Toronto.