What Do We Really Mean By

'Women's Fiction'?

Rachel Howard Recommends 6 Essays on the Gendering of Books

I wrote my novel in a writing group with two forty-something men, faintly guilty that these men’s wives, also writers, were watching the kids instead of joining our meetings (and trying unsuccessfully to persuade the wives that we could pool money for group childcare so they could join us). Writing a novel with two men as first respondents had an upside, though: It never occurred to me to wonder whether I was writing literary fiction, or “women’s fiction.” After all, two cis male dudes were into it. And then the novel sold. And shortly after the publication date was set, I saw it on lists of forthcoming books created by enthusiastic and kindly, well-meaning book bloggers—labeled as “women’s fiction.”

The rationale for this label was simple: the novel concerns family life and is narrated by a female main character. That rationale was also rife with assumptions: That books about family life aren’t for men and women both; that men don’t want to, or shouldn’t want to, read books narrated by a woman describing motherhood. And of course the label “women’s fiction” itself comes loaded with its own complicated assumption: that “women’s fiction” isn’t literary fiction.

Oh, God, that’s right, I thought with dread when the label cropped up. Gender is still a charged and inescapable factor in the publishing experience.

Fortunately, I had some preparation—even, as it were, a personal primer. In the years between my first book (a memoir) and this novel, I had watched debate rip over that problematic label “women’s fiction,” and had been privy to intense discussion within the Writers Grotto community in San Francisco, especially when articles on “pandering” by Claire Vaye Watkins and “Goldfinching” by Jennifer Weiner hit in 2015. Anecdotes and counter-anecdotes flew, until my head hurt. The problem with discussing misogyny in publishing is that empirical data is hard to come by. (Thank you, VIDA, for working to change this.)

The discussion needs to happen, though. It needs to keep happening, if women writers—if all writers—are going to find their ways out of false dilemmas and assumptions. The difficulty is exhaustion and overwhelm. When I saw the “women’s fiction” label applied to my book, I returned to that clutch of articles I’d hook-and-crook gathered on the contemporary reality of female literary writers—pieces I felt sidestepped in-fighting pitfalls and cut to some startling empirical experiments and semiotic insights. If I could teach a class on the realities of being a woman writer, these are the pieces I’d assign, with the syllabus always open to expansion—including Stacey D’Erasmo’s reflections of writing under a female name, published just this last year.

*

How to Pose Like a Man, Amanda Filipacchi

Preparing to pose for her author photo, Amanda Filipacchi made a discovery: “[M]ale and female authors posed differently. The men looked simpler, more straightforward. The women looked dreamy, often gazing off into the distance. Their limbs were sometimes entwined, like vines.” Filpacchi’s decision to “pose like a man” leads to reflections not just on male and female posturing, but to the biases we bring to art by women.

Homme de Plume, Catherine Nichols

Catherine Nichols ran an experiment: Would agents respond differently to her novel query if she sent it out from a man’s inbox? She discovered that “George” received a much higher response rate of agents requesting the full manuscript: “One [agent] who sent me a form rejection as Catherine not only wanted to read George’s book, but instead of rejecting it asked if he could send it along to a more senior agent. Even George’s rejections were polite and warm on a level that would have meant everything to me.” Nichols concludes that, submitting as Catherine, “I was being conditioned like a lab animal against ambition. My book was getting at least a few of those rejections because it was big, not because it was bad.”

The Second Shelf, Meg Wolitzer

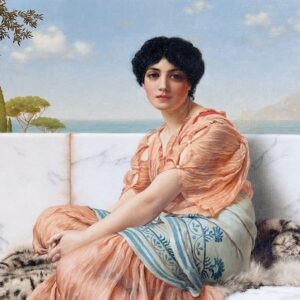

To my mind, this commentary by Meg Wolitzer, which I spotted when it first came out in 2012, still stands as the most clear-eyed take on “women’s fiction.” Prompted by the critical success of Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Marriage Plot, Wolitzer lays bare the arbitrariness of the label, “where I am listed, along with Jane Austen, Sophie Kinsella, Kathryn Stockett, Toni Morrison, Danielle Steel and Louisa May Alcott.” What I love most in this all-objections-anticipated essay, though, is her understanding of book cover semiotics: “just like the jumbo, block-lettered masculine typeface, feminine cover illustrations are code. Certain images, whether they summon a kind of Walker Evans poverty nostalgia or offer a glimpse into quilted domesticity, are geared toward women as strongly as an ad for ‘calcium plus D.’ These covers might as well have a hex sign slapped on them, along with the words: ‘Stay away, men! Go read Cormac McCarthy instead!’”

The Author Is Purely a Name, Elena Ferrante

In 2015, the online magazine Guernica published excerpts from her letters, collected in the book published as Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey in the United States. A key line from the letters, and headline of this excerpt, is “The author is purely a name.” I’m grateful to Ferrante that, writing under a pseudonym, she chose a woman’s name, and all the controversy that comes with that in combination with her honesty about female lives. She may respond to that controversy under the cover of anonymity (even after attempts to unveil her)—but she still devotes enormous time, energy, and intellect to the thorny problems.

The Subtle Genius of Elena Ferrante’s Bad Book Covers, Emily Harnett

More Ferrante. This analysis was a useful brain tonic as my publisher and I negotiated the delicate dance of landing on a book cover we all could embrace. Emily Harnett describes the hatred of Ferrante’s fans for her covers, and quotes Ferrante’s publisher that “many people didn’t understand the game we we’re playing, that of, let’s say, dressing an extremely refined story with a touch of vulgarity.” Further to that, this intentional vulgar dressing, Hanett argues, is a subtle ironic explosion of “the destructive stigma that has long been attached to ‘women’s fiction’ as a genre.”

My Year of Writing Anonymously, Stacey D’Erasmo

And a new one for the road. Stacey D’Erasmo, in an essay published this year, spends a year working under a pen name, and is surprised to realize how deeply and subconsciously the experience of writing under her real, female, name has come to inhibit her. It’s worth a long quotation (and worth re-reading the whole essay many times):

What I didn’t have a name for was something more insidious, an aesthetic odorless, colorless gas that, secretly, made me suspect that I would never, myself, be ‘literary’ enough and I have come to the unhappy conclusion this may, pace Woolf, have to do with gender.

What Woolf meant in her essay was that women writers used Anon because otherwise they wouldn’t be taken seriously or even published. It’s improved since Woolf was writing, but the publishing numbers and the distribution of prizes, grants, and awards continues to bear out the reality of this problem. My shame, however, had to do with something I suspected about women writers, Literariness, and damage. To wit: if you’re a woman who writes, and you want to be taken seriously in America, your female characters better be significantly damaged, mutilated, self-mutilating, self-hating, and/or anorexic either literally or psychically. Do not, under any circumstances, have a body that gives you anything but trouble, suffering, and humiliation. Alternatively, retreat up to the innermost recesses of your mind, like a nun in a bare attic. Issue pronouncements about metaphysical or political issues from that attic. These are the ways to be considered smart and serious, if you’re a woman who writes.

Whatever name we write under, whatever our identities public or private, my hope in offering this limited list is that we may all find our hard-earned way to freedom in our work.

Rachel Howard

Rachel Howard is a writer of fiction, personal essays, memoir, and dance criticism. Her debut novel, The Risk of Us, will be published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.