What Being an Editor Taught Me About Writing

Anna Pitoniak on the Inside Tricks of the Trade

I’m an editor at Random House, but for the last several years I’ve been writing around the edges of my day job: mornings, nights, weekends, wherever I can grab the free time. I began my first novel (which is publishing today) while I was working as an editor, and I credit my job with giving me the courage, and the tools, to tackle writing a book. The truth is that spending one’s life reading good writing—not just reading it, but thinking about what makes it so good—is the best way to teach one’s self how to do it. For some people, this might mean enrolling in an MFA program. For me, I was lucky enough to learn by observing the other editors around me, and working on manuscripts as they went from rough drafts to finished books. It was the best writing education I could have received. Here are a few of the things I learned along the way:

Writing is Revision

This won’t come as news to anyone, but I can’t stress it enough. The first draft is important, because you are working out the ideas and the plot on the page, and getting that first draft finished is an accomplishment, but what really matters is how many times you are willing to revise that draft. In my mind, this is where the role of hard work—as opposed to God-given talent—comes in. Some people are preternaturally gifted and can dash off a beautiful paragraph with no effort, but they aren’t necessarily the ones who are willing to revise, and revise again, and revise again, until their computer desktop is so cluttered with different drafts that the background is no longer visible.

When you are writing, you are attempting to communicate an idea to the world. In the first draft, the idea is still expressed in your own private language. It takes many revisions to clarify what you are really trying to say. As an editor, these are the notes I find myself scribbling in the margins of so many manuscripts: Clarify. Don’t get this. What does this mean? The language must be put through the wringer, over and over and over, so that when a reader finally picks up the book, they can say: I know exactly what she means.

Remain Flexible

In the early stages of writing, it’s easy enough to murder your darlings. The first draft is probably a mess, and everything feels negotiable. But by the time your editor comes into the equation, you’ve likely gone through many drafts, and you’ve reached the point where the story has settled into itself. As time goes by, it can be increasingly unappealing to make big changes. The best thing you can do is remain fully open-minded to suggestions—both minor and radical. You might think it too difficult to overhaul an entire character, or plot arc, or climactic event. That’s the way it is, and inertia is too powerful to overcome, right? Wrong! You built this book yourself, you know it better than anyone, and you can rebuild it if you have to. I’ve seen what happens when a writer is willing to make a big change at a late-stage point. Often it’s the very thing that ties the book together—it’s the magic final ingredient, the umami that was missing.

The Beginning is the Most Important

The reality of being an editor is that we read submissions quickly, and form judgments about them from a small number of pages. The beginning matters; it matters more than any other part of the book. As a writer, you only have so long to hook the reader. It doesn’t matter if, later on, the book is filled with gorgeous prose and heart-stopping suspense. And editors aren’t the only ones who form snap judgments about a book—someone browsing in a bookstore or using the “look inside” feature online is doing exactly the same thing. If the beginning isn’t strong enough, down the book goes. It pays to think carefully about the beginning, and spend an outsized amount working on it. Play around with it, try different things. What is the right moment, the right voice, with which to begin? Is it loud, or is it soft? Do you want to bring the curtain up on a moment of high drama, or instead set a tone or a mood that gives the reader a taste of the world? The beginning doesn’t have to contain fireworks in order to captivate. But it does have to captivate. It might not be clear what the beginning ought to be until the book is nearly finished, so don’t worry about it right away. Get the thing written, then go back to figure out where it should begin.

Pay Attention to Pacing

Pacing was one of those things that I never actually thought about until I was an editor. I took it for granted as a reader without understanding how it worked, sort of how I’ll take for granted a car riding smoothly without knowing anything about its suspension. It is one of the more mechanical aspects of writing, and for a lot of writers, it takes practice to become cognizant of pacing. As an editor, you start to see that there are inflection points, places where you feel your attention wandering and where the pace needs to pick up. Sometimes this means planting a hook: a new question or new complication that needs resolution, which will keep a reader turning the pages. Sometimes this means stripping the prose down: once a reader is immersed in the story, a writer no longer needs to supply so much detail and context (a reader can fill it in herself at that point) and the story can move faster. Pacing doesn’t necessarily need to be the first thing you worry about as a writer, but it is a layer you must work on after the words are on the page.

Skip the Stage Directions

One thing I always notice when I’m editing—and which I notice abundantly in my own writing—is excessive staging. When I’m working out a scene in my mind, I tend to think about a character moving around a physical space, and I’ll write the scene accordingly: she walks across the room, she opens the door, she sits down, she stands up, etc. To get my character from point A to point B, it’s necessary for me to visualize every part of it. But when I’m editing others’ work, I always cut that sort of stage direction (and I’m trying to get better at editing it from my own work). It’s weight that drags on the story. We don’t need to know how a character got across the room in order to believe that the character crossed the room. This is not to say that physical movements don’t matter—of course they do! Every rule is made to be broken, and sometimes you do need to know how a character got across the room. But if you are going to tell us what it looked like, it ought to be for a good reason. Which brings me to my next point.

Stop Clearing Your Throat

I think of visual staging like the above as one form of writerly throat-clearing, but this throat-clearing comes in many forms. Sometimes it is long and intricate sensory description. Sometimes it is dialogue that just keeps ping-ponging back and forth. Sometimes it is dwelling on an insignificant moment. These are the kinds of things that I tend to flag, as an editor. If its existence isn’t justified, then why is it there? Often it feels like preparation before we arrive at the real point—and if you’re asking a reader to stick with you for several hundred pages, it’s better to arrive at the point with expedience. Every sentence or passage ought to perform a function, whether it is moving the action forward, or developing a character, or deepening an emotion, or something else that truly enhances the story. I am wary of writing that is merely beautiful. And if you’ve convinced me that a character is a certain way, you don’t need to keep convincing me of that again and again.

It’s hard to be this ruthless on yourself in the early drafts of writing. You need to get the story on firm footing before you can start to see what is necessary, and what is superfluous. But, this is the great benefit to writing. You can be more articulate on the page than you are in real life. You might hem and haw while you’re speaking, but in writing, you have the chance to go back through and eliminate all of that throat-clearing.

What’s on the Page is What Matters

This is one of the biggest things I’ve learned as an editor, and it’s perhaps most useful in the latest stages of the writing cycle. If you are a writer who has found a publisher for your work, that is a wonderful thing, but it’s important to remember that the work will shortly be out of your hands. You won’t be able to completely control how the work is put into the world. You certainly won’t be able to control how it is received. What you can control is what’s on the page. As an editor, I’ve watched manuscripts ignite like wildfire across the publishing house—people read it, they fall in love with it, they can’t wait to talk about it with their colleagues. This is the magic that everyone hopes for. But the writer isn’t able to engineer any of this. The only thing a writer can do is write the very best book they can. Even when you are tired and bleary-eyed and sick of your own writing, when you can’t stand another round of copyediting and proofreading, it is worth it to ask yourself whether you have pushed the story as far as you possibly can. Is it the best it can be? Are you happy with it? Are you proud of it? That is what you ought to strive for, because that will always belong to you—that satisfaction and pride—no matter what happens once the writing is out in the world.

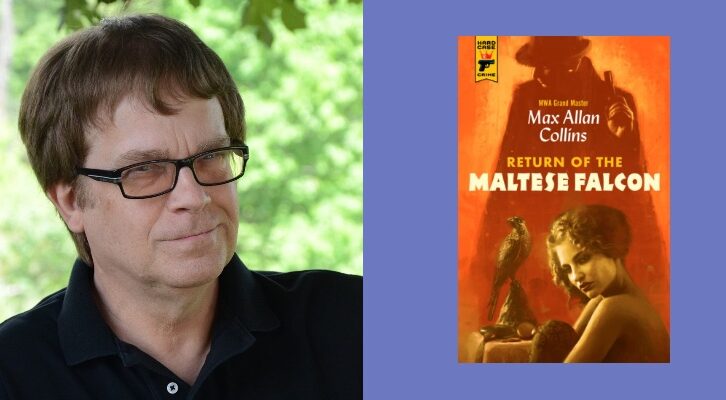

Anna Pitoniak

Anna Pitoniak is an editor of fiction and nonfiction at Random House. She graduated from Yale in 2010, where she majored in English and was an editor at the Yale Daily News. She grew up in British Columbia.