To the Lady Who Mistook Me for the Help at the National Book Awards

"Doesn’t something break just then, when you and I approach?"

Dear Lady at Table 24,

This two-piece fits me nice and slim. The jacket’s athletic cut is tapered along the torso. The sleeves flash a bit of French cuff. Just snug in the shoulders with the lapels’ gentle slope to the simple double button. Black, classy . . . and polyester.

The suit is $90. OK, $105 after getting the pant legs hemmed. That’s one decent night of drinks out in Manhattan or a take-home bottle of very fancy Italian red. It’s a used TV. It’s an Amtrak ticket round-trip from Philly to New York Penn. It’s a used parlor guitar with a cracked tuning peg. It could buy me enough kush to get me lifted twice a week for three months.

But I bought this suit right here to go cheer hard for some friends who are being celebrated at the National Book Awards. BLACK TIE, the invite says. My seat at the table costs me almost two and a half times the price of my threads. I pay up because I want to be in the room to dap my brothers and sisters up. Get it?

The crystal and silver is set over the clean white cloth. The hippest music is rocking Cipriani. Hundreds of glasses clink under the ceilings vaulted by these dramatic columns.

After the first round of drinks, after introductions and small talk with my tablemates, after the courses of salad and soup, I stand up, excuse myself, and walk across the swanky hall, winding my way through the other big round tables to find my way toward one of my dear friends, who is among tonight’s honorees. And you—sitting at a table not far from where my homeboy is sitting—stand up too. Surely, by the way you crane your neck forward and to the side, stepping slightly left into my path just enough to intercept me, I must know you from somewhere else, right? I lift my chin a little to see if I can link a name to your face. And surely you think you know me too, don’t you? I’ve traveled only from the other side of the room to walk toward you and for you to walk toward me. But doesn’t something break just then, when you and I approach? All the festive shimmering in the space. These eyes. This face. I think I’m even smiling now, when you point back at your seat to tell me you need a clean linen to dab the corner of your mouth. You need a knife for the beef cheeks. A refill of your cabernet. Maybe you need me to kneel down and shim one of the table legs to keep it from bobbing.

So this is how you and I have been walking toward each other maybe this entire time.

When at first I don’t respond, maybe you think it’s too loud for me to hear you clearly. Or maybe you think my English isn’t too good—for you ask me the same thing once more before you clip your request short and say: “You’re one of the servers, right? . . . You’re with the servers? . . .” And I stand there absolutely still so we might stare at each other for one long second exactly like that. “You’re not with them?” You are pointing at the line of workers in white jackets and bow ties, a tray hoisted over some of their shoulders. That’s when my face gets unfixed quick. I twist the whole thing—top right eyebrow to bottom left lip. I crinkle the bridge of my nose and suck my teeth once before I blow out a pffffh! You open your mouth and maybe if there were not the thousands around us chattering, pricking each other with their literary wit, the fine chime of restaurant china like a four-hour avalanche of muted porcelain, I think I might hear you whisper, “Oh . . .” You spin on one heel and dash back to your chair.

*

I want to show you this photo of an old man walking out of a building into the street with his hands full. He seems to lean to his right-hand side, which holds the bigger piece of luggage. In his left hand he holds a slightly more compact suitcase whose handle he hooks with his three smallest fingers so his thumb and forefinger can pinch some kind of stick—a broom maybe or baston. I love his bright panama hat with its clean flat brim and dark band. His pants are black, with a straight crease pressed down the front. Even with one foot forward, the hem doesn’t ride too high.

For this man, it is still 1977. Not a week before this picture was taken, officers of the City of San Francisco broke down the doors of Manilatown’s International Hotel in the middle of the night with a battering ram, then woke this old-timer and the 40 other residents on order of eviction, despite a decade of negotiations, resistance, marches, actions, and protests by thousands of folks from all around the Bay. The I Hotel residents were mostly Asians, most of them manongs, a term of respect for Filipino laborers who worked in America’s canneries, fields, and boats . . . They were poor, working-class folks and this was their home since the 1920s, the one place they could afford. Four days after the midnight raid and eviction, the manongs were allowed to go back and retrieve their belongings—like this gentleman in the photo—though their units had been ransacked and vandalized.

Look again at the picture, the high shine of his shoes’ leather. There’s something so familiar about this man. Too easy to say he could be uncle or cousin. One of my dad’s poker buddies in the 70s. When I look carefully at the man’s attire, I think of the wish that attire can make.

*

Dear Miss Lady at Fancy Table 24,

You know when some third-grade kid is giving his mom grief in a store, hanging all his weight from the strap of her handbag or hiding behind the curtains or climbing into the metal shelves to lie down? Yeah, that was me.

Once every couple months my mom dragged me to the Rag Shop, a fabric store on Route 18, just south of the entrance to Exit 9 on the Jersey Turnpike. The store was housed in a huge space with giant windows and so much light it made me want to puke. It was always so quiet. I don’t ever remember other customers in there, as if my mom was the store’s only patron. With no one home to keep me from setting fires or flinging steak knives at walls or passersby, my mother coaxed me into the car and had me tag along.

I was bored as soon as I stepped in. I remember the tables and tables of damask and trefoil, houndstooth and herringbone, floral and geometric, madras and lattice and paisley. (I once found the whitest, most expensive bolt and ran my grimy hands and forearms all over it, and even wiped my cheek still greasy from fast-food fries.) My mother would spend my precious child-time sliding her palm slow under one sheet and holding another against the light. She’d touch with her knuckles and pull the samples close to her nose, examining the fibers. She’d select this one and that one, yards and yards, heaping them on the counter beside the register, and then she’d haggle like hell, pick up her several bulging bags, and turn toward the door, smiling like she just robbed the place untouched.

*

My Dearest Lady of Table 24,

Let’s call what happens between us the Mistake.

The Mistake has billions of instances and archetypes and variations. I think of it as godfather to the All-Black-People-Look-Alike Mistake and the Brazilians-Speak-Spanish Mistake and the Let-Me-Just-Say-Konichiwa-to-Korean-or-Chinese-People Mistake. And maybe the Mistake you made was the He’s-Got-to-Be-the-Help-Because-He’s-Brown Mistake.

I’m supposed to believe this fresh, albeit inexpensive, suit is the Real Mistake. I’m supposed to believe I’ll never get away with this budget single-breasted outfit at a high-class soiree. Just a few weeks before awards night, I was striding down Bergenline Ave. in Union City when I passed this sale window teeming with cheap leather and zigzag sweaters, and I felt this little tug, this small yearning to slip into some fresh new fits with just barely wild lines, a chance to flip the fashion script and outdress the high-class gents who’d be in attendance at our shared shindig. It would just take a little frugal craft to make formal evening wear out of a simple but slick black suit bought from a dusty shop in northern New Jersey. And should I not have fallen a little in love with the gypsy woman from Valencia with a voice of straight whiskey whose sales pitch I bought in that province’s Castilian? Didn’t I drape that plastic bag over my shoulder already feeling the swagger of my get-up so hard that I left the store gliding out onto the public walk and then stepped aside without breaking stride to make way for the elder women of the avenue? Did they not acknowledge my chivalry? Did they not grace me with their affections by calling me caballero? Gracias, caballero!

I confess I didn’t give enough of a damn about the cheap synthetic reek, the whiff of it rising around me as I passed among the gabardine, barathea, pure silk.

*

Dear Miss Lady,

I grew up around the corner from the old Fedders factory and the Revlon warehouse and the Ford auto plant (which is now a series of strip malls along a six-lane stretch of US 1). When I was in grammar school, the other kids at St. Francis of Assisi came back from Christmas break with brand-new ski-lift tags still attached to their zippers. They carved the slopes with new gear at Shawnee and in Vermont while my parents took me and my brothers to visit Uncle Ernie and Tita Candi over at Hoyt-Schermerhorn across from Brooklyn’s Central Booking. Sometimes my parents missed the monthly on the piano in our living room. Sometimes Ma Bell cut our phone line for a while. Sometimes my mom had to rush a check so we could get the electricity turned back on. If you flipped the light in the kitchen late at night the roaches would scatter.

It was my mother who taught me to sew. I’d grown into a wiry, restless teen. It was the early 1980s, a brief few years when punk rock kids, b-boys, new wave freaks, and disco fiends might all get down on the same dance floor: this one in moccasin boots, this one in a track suit with three side-stripes down the sleeves and legs, this one in a baggy neon sweater and extra eyeliner.

I got just enough instruction from my mom that I could buy an eight-buck pair of black pants three sizes too big and hem the bottoms and taper the inseam so the ankle just barely let my skinny foot squeeze through.

I even learned to finesse the thread through a bobbin and control the fabric through her machine. I remember the music of her Singer. As a smaller boy, I used to sit underneath the table and slap rhythms on my lap or the concrete basement floor, keeping time with the motor’s falling and rising whine. Sometimes it held a steady tenor ostinato moan and I’d hum in unison or sing some rough harmony a major-third above. I loved how her heavy scissors grunted like a pig against the old oak dining table that my dad stained too dark and which she converted to a space to sketch and tuck, measure and fold, stitch and seam.

Yeah, it was my mom who showed me how to select the needle from her tomato, snip the bit of string, and find the eye.

*

Dear Lady,

I got a couple college degrees. I’m a writer. I’ve published a good bit. I’m a professor. I have an office, tiny as it is. My checking account has been overdrawn four times in the last six weeks. My bank stung me at $34 a pop. Throw that on top of almost six figures in debt; I don’t even own my sheepskin. My last dentist installed a crown to fix my back-left bottom molar, but the post shifted and cracked the root, so I’m doing it again after a new doc yanks the old tooth for another three grand. I’ve moved six times in four years. And now my landlord is selling this house whose third floor I rent. This summer I might be moving again.

*

Dear Lady at Table 24,

I keep thinking about those manongs of the I Hotel, kicked out in the middle of the night, the police and deputies barging through the double doors with a steel trunk. Cops in riot gear spill in from the street to clear the old men from their homes, some of them residents for half the 20th century. There is footage of those manongs gathered in the barbershop downstairs, the diner, the pool hall. This one is slender, this one has a paunch. They are slightly grumpy and all beautiful. Woven into their manner is both gravity and play—an affect you might get real good at answering to minor tyrants for the 10 or 14 hours you work under the surveillance of some other underpaid grunt.

I can imagine the body at work in the field. I can imagine that body up to work before the sun’s risen. I’ve watched my uncles and aunts in their own fields of peanuts and corn and sugarcane. I can imagine men on their various long roads home. Right now, I can imagine one man pushing a narrow wood door that opens onto his small room with a small bed and a good-enough window. At this hour, he probably stinks pretty bad. He’s probably sore and a little stiff in his back or the fat muscle of his left hand. He might rinse his face and scrub his armpits twice. The clear water in the basin will cloud with dirt, salt, maybe a touch of blood from a cut in the thumb reopened. The whole washing of the body—ass crack and groin to the creases between the toes until he is renewed by talc and the musk of his own long skin’s oils. The man comes clean.

Maybe he’s already begun to hum to himself. Maybe he gets lyrics to the American standard wrong. He’s not even smiling to himself yet. But the music’s already just under the tongue. He’s already forgotten the stupid shit the foreman or field manager shouted down to him and his buddies. I don’t have to wonder too hard what men like this do with the first forbidden twitch to strangle an overseer. How that wince is held back, pulled in. How the whole arc of his fist, the turn of the hips, the shoulder’s quick pump, time and time again are stored away, like a journal for the working body, a vocabulary one might keep, a babble, a violence, a nonsense, a bestiary of brutal motion, each figure honed into a slight bow of the head, a loosening of the fingers to the first knuckle, how one might peek through the top of his eyes so as not to look directly upon a boss who is gazing back.

Can you see the body getting older? Can you see the unburdening? The sloughing off of the more dangerous self? Can you see the man slip each leg into his boxers and a clean white T-shirt? At this hour, in this light, the cotton’s coolness softens him.

*

Dear Lady at Table 24,

I confess I have loved you a very long time. And often more carefully than I have loved myself.

I see you. Dear Other,

Dear Faraway,

Dear Come-close-now,

A style is not a category or season. It is not a box or bracelet or coat. It’s not a dance or strut. Style is a perplexity. A becoming.

*

My aunt picked the dress my mother was buried in. I can’t remember it exactly, but the material was light, maybe had embroidery. I can’t recall if it was something my mom made herself. I hope it was. I’d love to know she could brag a bunch in the afterlife.

*

I’m holding my arms up straight and sliding the silky black over my shoulders and guiding my hands through the short sleeves. I’m twisting the waist so the neckline’s centered. I’m putting on your slender dress. I have already stepped one clumsy foot at a time into the panties, found the bra’s clasp and clicked it into place, tugged it twice to cradle my sad man tits. Now I’m feeling for the single hole in each lobe to guide the diamond’s post through my ear and into the backing—first the left, then the right. I still can’t change this face, so I’ll gently point my foot over the arch and into the high heels’ open toe. First the right, then the left. I love the short swift current, these little gasps the fabric makes around my thighs even in small turns. Now I’m admiring my knees, my calf. Now I’m bending down to buckle the gentle ankle strap. I don’t know how I’ll climb out of the cab with any grace or make the modest ascent of stairs, let alone dance my ass off at the after-party. Am I a woman? A millionaire? A peasant? A thief?

*

Dear ,

The word style is cousin to stylus. It comes from the Latin “to etch.” Or “to engrave.” And so, style is a way to inscribe oneself upon the world, but also a way to dig, to delve into, to investigate. Style is, then, an inquiry. Style, furthermore, because it is a way to engrave, is also a way to carve a place into some landscape, a hole. That is, style is a way to prepare the earth for the body.

There were early mornings, before my mom left for her job, when she stood in her housedress as she pored over all this fabric pinned to translucent tan sheets. They seemed an elaborate secret code, the dashes marking the cuts and seams, minor prophecies of the limbs’ movements, articulations of the shoulders and hips, maps of an outer body and maybe even its inner space. The cotton sheets would run along the plate’s feed dogs guided by her fingertips; she’d thumb a switch then ease her foot into the pedal like a rocket pilot. She’d hold the material flat, easing it through at gentle angles. In less than an hour she’d bite the last thread free of the machine with her bare teeth. And she’d have crafted a brand-new skirt or blouse for work in time to shower, pat her waist once in front of the mirror, jump in the car and go.

*

Dear ,

One who slips on a fine set of threads does not become rich or worthy. He doesn’t become boss or white or soldier or stallion. Instead, she enlists the outer rituals of work: the undressing, the washing, the slow dressing again into sleeker yarns. A way to touch and be touched. A way to see one’s self before being seen. In the Mistake, one becomes nothing but a certainty. In true style, one becomes a question. It allows us to hold for a while the possibility of fascination and the preface for awe. Only when style frees us into its peculiarities, confusions, or bewilderment does it ready us for the strangeness of living and maybe even a few humble kinds of love.

__________________________________

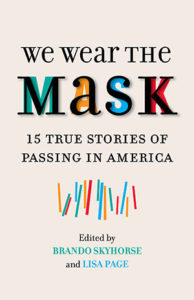

From We Wear the Mask: 15 True Stories of Passing in America, ed. Brando Skyhorse and Lisa Page. Used with permission of Beacon Press. Copyright © 2017 by Patrick Rosal.

Patrick Rosal

Patrick Rosal is a multi-disciplinary artist, essayist, and author of five poetry collections, including The Last Thing: New and Selected Poems, listed among the best books of the year by The Boston Globe. A Distinguished Professor of English at Rutgers-Camden, he has been awarded fellowships from the John S. Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts and serves as inaugural Campus Director of the university-wide Institute for the Study of Global Racial Justice.