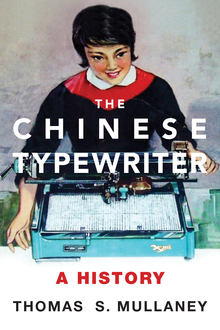

To Abolish the Chinese Language: On a Century of Reformist Rhetoric

Thomas S. Mullaney on Theories of Chinese Modernization

China has undergone profound changes over the past 500 years. At the midpoint of the last millennium, Ming dynasty China was one of the engines of the world economy, one of its largest population centers, and a sphere of unparalleled cultural, literary, and artistic production. Over the ensuing centuries, China witnessed a transformative conquest by a non-Chinese dynasty from the northern steppe; a doubling of the empire’s size, as the consequence of immense Eurasian military campaigns into present-day Mongolia, Xinjiang, and beyond; a period of unprecedented economic and demographic growth during the 18th century; the emergence of ecological and demographic crises that spawned the largest and most destructive civil war in human history; colonial incursions by multiple Western nations that rewired the circuitry of global power; the demise of an imperial system over two millennia old; and a period of widespread political and social experimentation and uncertainty.

During the anxiety-ridden 19th and 20th centuries in particular, Chinese reformers of multiple political persuasions engaged in thoroughgoing critical reevaluations of Chinese civilization in an attempt to diagnose the cause of China’s woes, and to identify which aspects of Chinese culture would need to be transformed to ensure their country’s transition into a new global order intact. Targets of criticism included Confucianism, government institutions, and the patriarchal family unit, among many others.

For a small but vocal group of Chinese modernizers, some of the most impassioned criticism was trained on the Chinese language. Chen Duxiu (1879-1942), a founding member of the Chinese Communist Party, famously called for a “literary revolution” to overthrow the “ornate, sycophantic literature of the aristocracy,” and to promote the “plain, expressive literature of the people!” “In order to abolish Confucian thought,” the linguist Qian Xuantong (1887-1939) wrote, “first we must abolish Chinese characters. And if we wish to get rid of the average person’s childish, naive, and barbaric ways of thinking, the need to abolish characters becomes even greater.” The celebrated writer Lu Xun (1881-1936) was yet another member of this anti-character chorus. “Chinese characters,” he argued, “constitute a tubercle on the body of China’s poor and laboring masses, inside of which the bacteria collect. If one does not clear them out, then one will die. If Chinese characters are not exterminated, there can be no doubt that China will perish.” For these reformers, abolishing characters would constitute a foundational act of Chinese modernity, unmooring China from its immense and anchoring past.

To abolish character-based writing invited serious peril, however. What would become of China’s vast corpus of philosophy, literature, poetry, and history, all written in Chinese characters? Might not this inestimable heritage be lost to all but the epigraphers and specialists of tomorrow? Were China to abandon characters, moreover, what would become of the country’s pronounced linguistic diversity? Cantonese, Hokkienese, and other so-called “dialects” of Chinese are as mutually distinct as Portuguese and French. Indeed, many have argued that the coherence and persistence of the Chinese polity, civilization, and culture have in no small part been predicated upon the unifying influence of a common character-based script. Were China to go the route of phonetic writing, would not these linguistic differences in the oral realm be made more insurmountable, and politically charged, once formalized in writing? Might the elimination of character-based writing precipitate the breakup of the country along fault lines of language? Might China cease to be one country, and instead become a continent of countries, like Europe?

The puzzle of Chinese linguistic modernity would appear, then, to be a perfectly irresolvable one. Characters held China together, but they also held China back. Characters maintained China’s connection with its past, but so too did they isolate China from the Hegelian sense of historical progress. How then was China to make this seemingly impossible transition?

*

Returning to the 21st century, where the passages of Lu Xun and Chen Duxiu continue to bejewel the syllabi of countless undergraduate lecture courses on modern Chinese history (and scholarly writings alike), a world presents itself that hardly anyone could have anticipated at the dawn of the 20th. Chinese characters were not exterminated, and yet China did not perish. Not only are Chinese characters still with us, clearly, but they form the linguistic substrate of a more vibrant world of Chinese information technology than even its most avid defenders could have dreamt of: a spectacularly large and growing presence in electronic media, widespread literacy, an ever-increasing network of Confucius Institutes and early education immersion programs propelled by foreign interest in the acquisition of Chinese as a second language, and continued popular fascination with Chinese characters that has manifested itself in not a few regrettable tattoos. More than ever before, Chinese is a world script. Throughout most of the past century, most assumed that such an outcome was conceivable only if China abandoned character-based writing, and underwent thoroughgoing alphabetization—which it did not. This outcome was not supposed to have been possible, and yet here we are. What happened? What did we miss?

The answer to this question is complex. At the outset, however, one key element can be outlined plainly: In sharp contrast to the popular trope that winners write history, in the case of modern Chinese language reform, it is the losers of history who have managed to command the greatest attention of scholars—the Chen Duxius, Lu Xuns, and Qian Xuantongs. Collectively, we have been enamored of this vocal minority’s brand of easy iconoclasm: incandescent, seductively quotable, yet ultimately naive calls to abolish characters, or to replace Chinese writing wholesale with English, French, Esperanto, or one of a variety of competing Romanization schemes. Meanwhile, we know virtually nothing about those who made possible China’s contemporary information environment: iconoclasts who were no less passionate, and yet whose work was grindingly technical, dogged by intractable challenges, but ultimately of unparalleled success and significance. Unlike their celebrated and well-known abolitionist counterparts, the builders and users of the modern-day Chinese information infrastructure never appear on course syllabi, nor are their writings canonized within source compendia on the history of modern China. Indeed, they were often anonymous even in their own times, leaving behind fragmentary sources about their work, and in all but a very few cases never achieving any celebrity.

For these language reformers, the question of Chinese linguistic modernity was never the stark binary advocated by Lu Xun and Chen Duxiu: In the modern age, are Chinese characters to be, or not to be? Theirs was a far vaster, more open-ended, and thus more complex question: In the modern era, and particularly in the modern information age, what will Chinese characters be, and how will the “information age” itself be transformed in the process? Seductive though it may be, To be or not to be? was never the primary question of Chinese linguistic modernity. The question was: To be, but how?

When we move away from the simplistic iconoclasm of character abolitionists, an entirely new history of the Chinese language comes into focus. No longer in the realm of Confucian ethics or Daoist metaphysics, where Chinese characters were criticized by some as the very repositories of antimodern thought—as the “the very nests and lairs in which poisonous and corrupt thoughts reside,” to pull another gem from Chen Duxiu’s abolitionist jewel box—we find ourselves in the admittedly less sensational yet decidedly more vital realm of Chinese library card catalogs, phone books, dictionaries, telegraph code books, stenograph machines, font cases, typewriters, and more—the infrastructural subbasement of Chinese script whose systems of inscription, retrieval, duplication, categorization, encoding, and transmission make it possible for the above-ground “Chinese canon” to function. We find ourselves in the plumbing and the electrical grid of Chinese.

Throughout the early 20th century, just as some language reformers were critiquing the Confucian classics, many publishers and educators decried the average time required to find Chinese characters in the leading dictionaries of the era; library scientists lamented how long it took to navigate a Chinese card catalog; and state authorities bemoaned the inefficiency of retrieving names or demographic information within China’s immense and growing population. “Everyone knows that characters are hard to recognize, hard to remember, and hard to write,” one critic wrote in 1925. “But there is a fourth difficulty in addition to these three: they are hard to find.” These were problems, moreover, that could not be solved through mass literacy, the simplification of characters, vernacularization, or any of the other lines of action so often treated as synonymous with “language reform.” And if these problems proved insoluble—if it proved impossible to build a telegraphic infrastructure for Chinese, or a Chinese typewriter, or a Chinese computer—then arguably even the most well-meaning efforts at mass literacy and vernacularization would not be enough to realize the ultimate goal: to usher China into the modern era.

__________________________________

From The Chinese Typewriter by Thomas S. Mullaney, courtesy MIT Press. Copyright 2017, Thomas S. Mullaney.

Thomas S. Mullaney

Thomas S. Mullaney is Associate Professor of History at Stanford University and the author of Coming to Terms with the Nation: Ethnic Classification in Modern China.