This Could Happen To Us: 10 Literary Apocalypses

On the Eve of the Election, Fictional Disasters from the Last Five Years

At this point in the election cycle, both Democrats and Republicans are screaming apocalypse, and the rhetoric is so inflamed that at times it can be hard to see the flames for the smoke. Where to look? Which version of the end-times is most plausible? I now find myself identifying with Riley Finn, the Most Boring Boyfriend of Buffy Summers, who famously stammered, “When I saw you stop the world from, you know, ending, I just assumed that was a big week for you. It turns out I suddenly find myself needing to know the plural of apocalypse.” Yes, we may be facing more than one apocalypse, and without the benefit of superhuman help. But what kinds of apocalypses should we be looking out for? As in all things, I went to the literature to prepare myself. So behold, if you dare: a necessarily incomplete list of literary visions of the future published in the last five years.

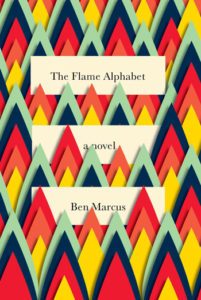

Ben Marcus, The Flame Alphabet

Language has power, as we all know. But generally, there are limits, at least in terms of direct damage-dealing. In this novel, however, language has been weaponized. Specifically, the language of children has become toxic to adults, resulting in the silencing of the world, and an attendant societal breakdown. “Pain is too soft a word for the reaction,” Sam, the narrator, explains. “Crushing was more accurate, an intolerable squeezing in the chest and the hips.” That might or might not remind you of listening to the speeches of one particular (and very large, and very orange) child.

Paolo Bacigalupi, The Water Knife

Stockpilers all over the country already know: the future is going to be about water. Bacigalupi’s most recent novel imagines a near-future America torn apart by drought. But some do have water—fancy resorts for the wealthy stand like palaces in miles of dust—resulting in a complicated system of corruption, violence, deprivation and control, in which the rich get wetter and the poor get drier, and everyone is looking for a drink.

Nathaniel Rich, Odds Against Tomorrow

Or, perhaps you’d prefer the other side of the coin: not drought, but flood. In Rich’s scarily prescient novel (it was written pre-Sandy), a hurricane hits New York, flooding the city, and making Mitchell Zukor, a disaster consultant for major corporations, into a strange kind of star. Given the near fortune-telling of this book, I think that, just for safety, it would be best if Rich’s next novel could predict a world where everything turns out ok.

Olivia A. Cole, Panther in the Hive

Our dependence on technology (and our bizarre health care system) might be the beginning of the end. In Cole’s version of the future, those with high-end health insurance (read: the wealthy and powerful) have been outfitted with chip implants that prevent all disease—but just before the novel begins, the chips go haywire, turning all of their owners into murderous monsters. A chipless girl named Tasha, wielding a kitchen knife and a Prada backpack, must navigate this instantly apocalyptic Chicago, fighting her way towards what may be only a rumor of help.

Laura van den Berg, Find Me

In this novel, a strange epidemic has taken hold of the country—it starts with silver blisters and amnesia, and ends up killing its victims. It’s poetic, really, how the loss of memory leads so swiftly to death. Joy, of course, is immune, which turns out to be almost as dangerous. Worth noting, too, is the way Van den Berg acknowledges the every day apocalyptic-ness of America in this novel: “For as long as I could remember, the weather had felt apocalyptic. Y2K fever and the War on Drugs and the War on Terror. The death of bees and the death of bats and radioactivity in the oceans and ravenous hurricanes. I though the country was like a fire that would rage and rage until the embers lost their heat, but instead the sickness appeared and within two weeks it had burned through the borders of every state in America… Our borders with Mexico and Canada were closed. For once, no one wanted to come in. And they definitely didn’t want us coming out.” Well, I guess that’s one way to solve the immigration issue.

Emily St. John Mandel, Station Eleven

Arguably, the most common cause of the end of the world in literature is some variation on the pandemic. This much-celebrated novel kills most of the world off with the flu (Russia sent it over in a passenger plane), but what’s most compelling are those who are left—a traveling group of actors and musicians trying to keep Shakespeare alive in the shattered world.

Karen Thompson Walker, The Age of Miracles

Here’s a unique apocalypse: what if the earth simply began to slow down? What would happen to a society unhooked from time, with its gravity blurred? And what, Walker asks, would happen if you were trying to grow up—its own kind of apocalypse, of course—at the same time? On the plus side, I don’t think that any election result could make this particular apocalypse happen. But knock on wood.

N.K. Jemisin, The Fifth Season

“Let’s start with the end of the world, why don’t we?” is how this novel begins. “Get it over with and move on to more interesting things.” The apocalypse (though again we need the plural) is geologic, meteorological—the land, called the Stillness, is in constant flux, breaking open, spewing out, coming down. The novel follows three women with special powers to control the elements as they make their way through this treacherous world. But in a world like this, what actually counts as the apocalypse?

Michel Faber, The Book of Strange New Things

Most apocalypse novels plant the reader directly at the end of the world—or at least in the scrum of the aftermath. But in this book, we see earth crumble through the eyes of Peter, a missionary on an entirely different planet, receiving news of disaster (dissolving governments, dissolving land masses) from his wife, who seems further and further away. “The world changes too fast,” a driver observes early on. “You take your eyes off something that’s always been there, and the next minute it’s just a memory.”

Colson Whitehead, Zone One

Hey, it could always be zombies.

Bonus!

Lucy Corin, One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses

The apocalypses in this book—most just a few lines long, because sometimes that’s all it takes for the apocalypse, some a paragraph or more—are not necessarily global. They can be the end of a relationship, or a moment, or an idea, because any of these can feel like cosmic destruction. None of these apocalypses are likely to caused by Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump, but they do serve as a reminder of what havoc we can wreak on ourselves.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.