The Story of the Philosopher-Artist of L.A.

On the Life of Noah Purifoy, Keeper of the Watts Towers

In essence Art and Creativity are eons apart.

Creativity

is the act of doing

void of the idea of productivity.

Art is what people say about Creativity.

–Noah Purifoy

Noah Purifoy composed these words in 1967. It was one of his more poetic missives, which appeared in the various catalogues, newsletters, formal presentations, and personal letters in which he set out his views on creativity and art production. They reflected his training as an educator, social worker, and artist; this preparation led him to seek out art whose meaning had a purpose and reflected expanded human creativity and connection, something that led to a better life for both artists and audience. In a self-published newsletter called One to One: Quarterly Report on Aspects of Creativity, the same publication where the words above appeared, Purifoy further elucidated how assemblage in particular—and its very notion of connecting, assembling, joining, and linking objects and ultimately people across myriad divides—would become his method and battle cry:

We wish to establish at the outset that there must be more inside of Art than the creative act; more than the sensation of beauty, ugliness, color, form, light, sound, darkness, intrigue, wonderment, uncanniness, bitter, sweet, black, white, life, and death. There must also be a Me who is affected permanently.

Assuming that the assemblage puts together two or more unrelated inanimate objects, transpose the concept thus: two or more seemingly unrelated inanimate objects assembled constitutes the possibility of communication. Here art becomes something other than—other than as many opinions as there are people. Art can become a new thing when and if it is virtually and willfully used as a symbol through which someone becomes better.

Art of itself is of little or no value if in its relatedness it does not effect a change. We do not mean a change in appearance of physical things but a change in the behavior of human beings.

The very notion of linkage and connection that assemblage represented, the assemblage aesthetic if you will, became a trope that described and defined Purifoy’s practice as an artist and more broadly as a cultural worker and philosopher. It helped him join the disparate parts of his own life together into a related whole. True to the form itself, these elements—the creative and social-purpose sides of his life—did not always reside in easy proximity or harmony. When art and life were playing well together, the result was art’s ability to act as catalyst, as change, not necessarily as “art” in the Western sense but dissolved into a more general and less elitist notion of creativity.

Purifoy’s concept of art-as-change was informed by his interest in existentialist philosophy. Writings by Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, De Beauvoir, and others popularized in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s were birthed in the French Resistance of World War II and immersed in ideas of freedom, political action, and the absurd aspects of reality. They also affirmed existence, focusing on individuality in the face of mass standardization. This trajectory of thought connected with the Beat Generation and the civil rights movement that was emerging at midcentury. The artist also absorbed the writings of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger and ideas advanced by Freud.

Analyzing the artist’s statements and projects in a variety of contexts, conceptions of phenomenology seem particularly useful in their engagement with the study of being, the “lived experience of inhabiting a body,” and how these could be applied to the contexts of a new subject, one born in rebellion. One got at the “living experience of meaning” by bringing focus to the human encounter of the world through objects that were “reachable,” grasped in the “bodily horizon.” However, Purifoy’s line of thought also relates to the emergence of African American modernist art practice during the 20th century and philosophies of art making that were linked to self-expression, imbricated with cultural nationalism and antiracism. In particular, his concept of art-as-change relates to the notion of black cultural accomplishment as the key to ending prejudice found in ideas developed during the Harlem Renaissance/New Negro Movement of the 1920s.

For example, Alma Thomas, a painter who came of age during the earlier period but whose recognition arrived in the mid-1960s, understood that art had the power to dispel ignorance and racism because people with a “sensitivity to beauty” and culture were superior, moving on an elevated plane. “A cultured person is the highest stage of the human being,” Thomas said. “If everyone were cultured we would have no wars or disturbance. There would be peace in the world.” Purifoy’s art-as-change loses much of the language and framework of elitism, the baggage that comes with high culture, with which Thomas had no problem. Still, in Purifoy’s mind, art had to be “willfully used as a symbol through which someone becomes better,” casting art’s active use similar to Thomas’s Harlem Renaissance thinking. Art’s progressive force, its capacity to cause someone to be a “better” person, also demonstrates its connections to social science, its ability to address and eradicate social inequity. The target of art is not only the elite viewer who would be transformed by the work—Thomas’s “cultured person”—but also the psyche of the maker. In a sense, Purifoy’s dream was informed by his experience with social work, a relationship to social science/philosophical discourses generally, and perhaps black social science schemas specifically. In a coded way, art-as-change addressed racism and the so-called “Negro problem” by being a catalyst to transform and eradicate the thoughts and behaviors that accompanied them.

There is no doubt that Purifoy saw sociological theory and concepts of social work as ways to address and change African American existence. Likewise, art played a similar role in his decisions and focus. Building and creating things had always been a part of his life. For Purifoy, the other artists in this study, and the majority of black people living in poverty at the time, making art was part of making do. Born in 1917 in the small rural town of Snow Hill, Alabama, he was the eleventh of thirteen children of farmers and sharecroppers. Like people with limited means everywhere, they made things, recycled, improvised something out of nothing. Purifoy, for instance, created things to play with, like a scooter from discarded roller skates.

Purifoy was able to attend college in the Depression-era South, graduating from Alabama State Teachers College in 1939 with a BS in education. As he tells it, he forced the issue, hanging around the campus in Montgomery after he was rejected, until he eventually was admitted. He worked his way through college as a janitor. With his degree in hand, like so many of his African American peers, the best job Purifoy could find was teaching industrial arts at the high school level, so he became a shop teacher. After three years of teaching in various schools in Montgomery, Purifoy volunteered to serve in World War II, as a way to change his life. His degree and experience translated into a position as a carpenter’s mate first class with the Navy Seabees. He was assigned to the construction battalion, building airfields and Quonset huts and preparing military camps. After the war, he headed to Atlanta University, getting a master’s in social work in 1948, then working in social services in Cleveland and the Los Angeles County Hospital. By the mid-1950s, however, he’d left social work behind, and he dedicated himself to art and art-related jobs for much of the rest of his life.

Purifoy attended Chouinard Art Institute, focusing first on industrial design and, when that was discontinued, changing to fine arts. He took a night shift at Douglas Aircraft, cutting templates on a shearing machine. He eventually switched from the strenuous work at Douglas to occupations closer to what he was being trained for—interior and furniture design, supporting his art making through the commercial art sector. Purifoy created furniture for the Angelus Furniture Warehouse and served as a window trimmer for Cannel and Schaffen Interior Designs on Wilshire Boulevard and the Broadway department stores, a gig he held for almost a decade. He also had his own company for a time with partner John H. Smith, another black art student at Chouinard (whose other job was mail carrier). But by the early 1960s Purifoy had moved away from the commercial sector as well, unable to pierce the glass ceiling as a black interior designer, even with his own company. He returned to the night shift, working as a janitor.

After leaving the commercial art sector Purifoy “came home, and just sat around for a year thinking about doing art. . . I had a studio clean enough to eat off the table. I never did a lick of work there. I had a beret and all. I ate cheese and drank wine, but I wasn’t an artist yet until Watts. That made me an artist.” While much of this is true, particularly as it reveals Purifoy’s ambivalence to a career as artist, in fact he did make things in the 1950s and early 1960s, collages inflected with Asian and African overtones as well as furniture. His apartment became the hangout, the place where people gathered for a certain kind of community and to “wrassle” with notions of art and aesthetics. “I wasn’t even an artist, but they flocked around me anyhow because I pretended to be an artist,” he said. “I’d graduated from art school, and I had ten years of experience vaguely with artists. So I was accepted as an artist. In fact, I didn’t have anything to show for it.”

What he did have was an elaborate hand-built sound system. People came from all over to experience his nine feet of speakers and to listen to his thoughts about art. Purifoy’s theories and philosophies would have an impact on generations of artists in Los Angeles—from John Outterbridge and John Riddle, who both came to understand art as tool for change, to David Hammons. In walking the line between artist and nonartist, taking a vow of poverty, and using found materials, Hammons paid homage to the older artist.

The work that really put Noah Purifoy on the map came in the mid-1960s: his connection with the Watts neighborhood and his interest in creating an urban environment where art could mobilize and energize black people. In 1964, he was asked by Eve Echelman of the Committee for Simon Rodia’s Towers in Watts to look after the Towers and the small school that operated there. He is credited as the founding director of what would become the Watts Towers Arts Center (wtac), a site for classes in visual and performing arts, primarily for young people, as well as exhibitions and concerts. It also became a place where artists found employment. Eventually Senga Nengudi, John Riddle, Suzanne Jackson, Curtis Tann, and John Outterbridge, among others, would offer their talents at wtac.

The famed Towers, which have marked that site for most of the 20th century, are among the earliest as well as the longest-lasting evidence of Watts as a cultural hub. Created by Italian immigrant and laborer Simon Rodia between 1921 and 1954, they are composed of a series of interconnected spires of steel rods and concrete, embedded with shells, stones, broken glass, and all manner of refuse, brought together in a mosaic-style surface. The structures, including fountains and birdbaths, reach almost one hundred feet at their highest point. After Rodia abandoned the property in the mid-1950s, the Towers began to deteriorate from lack of upkeep. During the age of urban renewal, the city cast its eye on the Towers as a site for removal. Because they were located in what had become the African American neighborhood of Watts—seen as unclean and dangerous—it was a likely site for reform. The Committee for Simon Rodia’s Towers was formed in the late 1950s to protect this amazing landmark.

The committee pushed to preserve a structure that would come to represent the city of Los Angeles, but it also had to deal with the now African American neighborhood that surrounded the locale. As Cecile Whiting points out, to engage the community and attract attention and support the preservation project, the committee began to conceptualize the area as a site for cultural activity.

In 1961, it began offering summer workshops for children. In 1963, the year the Towers were designated a Cultural Heritage Monument, the committee sought to expand its offerings to teenagers and professionalize these classes through the development of a community arts center. Its mission would be to address “problem” youth by using the arts as a tool of cultural uplift, which at once demonstrated art’s value and the good works that Watts Towers could perform. Such strategies had been used in the United States since the late 19th century and were standard practice during the New Deal. To attract neighborhood investment in the site, the committee looked for a qualified African American to take on a leadership role. Trained in both the arts and the social sciences, Purifoy had the perfect credentials for the job. It was not only, as Whiting details, that both the committee and Purifoy were interested in notions of “uplift”—it was that such notions had been part of African American creative and social culture throughout the 20th century. They found resonance with Purifoy on a number of important levels, not least of which was the way he could combine his interests in art and social work.

__________________________________

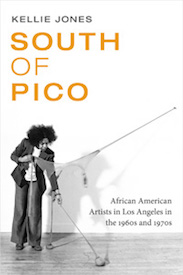

From South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s, by Kellie Jones. Courtesy Duke University Press, copyright Kellie Jones, 2017.

Kellie Jones

Kellie Jones, a 2016 recipient of a MacArthur "Genius Grant," is Associate Professor of Art History at Columbia University and the author of several books, including EyeMinded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art, published by Duke University Press. Jones has curated numerous national and international exhibitions, including Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles, 1960–1980 and Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties.