The Louvre Has Survived Wars, Uprisings and Yes, a Plague

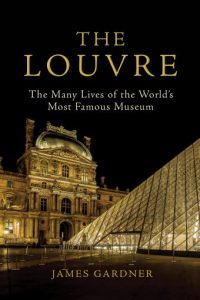

James Gardner Shows Just How Much the Museum Weathered

Perhaps the two most dispiriting words in the French language are sauf mardi, “except Tuesday.” Tuesday is the one day of the week when the Louvre—together with most museums in France—is closed. This has been the case for as long as most modern Parisians have been alive. Despite my many visits to the museum, that weekly closure has always felt like a cloud passing before the sun: the breeze off the Seine seems to blow a little cooler and a bit of color is drained from the landscape. By the same logic, however, when the Louvre reopens on Wednesday morning, it is as if that sunlight has returned.

In New York, where I spend most of my days as an art critic, I have a professional—but also a sentimental—involvement with places like the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Although for decades this grand institution was closed on Mondays, some ten years ago its directors decided to keep it open throughout the week. And although I don’t visit the Met every Monday, still, for reasons I can’t quite explain, the fact that it’s open, that it’s there for me if I need it, feels infinitely comforting and consoling.

Now, however, both the Louvre and the Met and every other museum I can name are closed indefinitely. Although the Met, which shuttered in mid-March, has suggested that it will reopen in July, the Louvre, which closed around the same time, will remain closed, according to its website, jusqu’à nouvel ordre, until otherwise instructed.

For the Met this decision is unprecedented. Other than when it shut down for a week in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, I am not aware of its being closed for any length of time on any other occasion. Throughout the First and Second World Wars, and—more pertinently in the present context—throughout the Spanish Flu epidemic from 1918 to 1920, the museum remained open.

Part of the reason for this remarkable consistency is that, at least in the past 200 years, New York has not had to worry about being overrun by foreign armies or to contend with an uprising of its own citizens. The Louvre, by contrast, has never had that luxury. During the 227 years of its existence—it opened to the public on November 8th, 1793—it has been menaced four times by the threat of foreign invasion and on several other occasions it came under existential threat from the Parisians themselves.

After Napoleon’s disastrous loss at the Battle of Leipzig, the combined armies of Russia, Austria and Prussia descended on Paris in 1814, resulting in the restoration of the Bourbon dynasty and the closure of the Louvre for three years. During the popular uprising of 1830, which ousted the Bourbons, not only was the museum closed again, but fighting broke out in front of the Colonnade, its great eastern entrance. Many died in the resulting conflict, with dozens of bodies buried in the museum’s landscaped parterres, including—it was rumored—several mummies from the department of Egyptology.

Four decades later, in 1870, the Prussian army laid siege to the French capital, and for the first time in its existence, but hardly the last, the Louvre not only shut down, but also sent its paintings into exile. On September 2nd, Edmond de Goncourt, that indefatigable diarist, wrote that “In the evening, after dinner…I saw seventeen crates containing the Antiope [of Correggio], the most beautiful Venetians, etc.—those paintings that had seemed attached to the walls of the Louvre for all eternity and now are nothing more than luggage.”

Only a few months after the Prussians left, during the Communards’ occupation of the capital, some of their more radical members burned to the ground the Tuileries Palace (which was connected to the Louvre) and they would have set fire to the museum as well, but for the quick thinking of its curators.

At the outset of World War I, parts of the Louvre’s collections initially remained open: but when, in 1918, two shells from a Krupp howitzer exploded in its gardens, the entire museum shut down for nearly a year, opening up again only in February of 1919—ironically, at the height of the Spanish Flu epidemic. And although Paris and the Louvre were spared the worst during the Second World War, already by 1938 gas masks were being issued to the curatorial staff and by the time the Germans arrived in 1940, most of the art had been sent, yet again, to distant parts of the country.

Between then and now the Louvre would shut down several more times, during the May uprisings in 1968, after 9/11, and over and over several tense weekends in recent years, when protesting members of the Yellow Jacket movement overwhelmed the streets of Paris.

And now we have the Coronavirus. For all its devastation, it has been a great clarifier. It has enabled us, indeed it has compelled us, to see how extraordinary and magnificent are some of those things that, until several weeks ago, we thoughtlessly accepted as our natural and inalienable right as citizens of a free and prosperous state: going to a concert, dining out, simply walking down the street.

But few institutions embody that freedom and that elevation more evocatively than our museums. Never again will we take them for granted, and never again will we assume, as before, that their masterpieces are simply there, “for all eternity.”

__________________________________

James Gardner’s book, The Louvre: The Many Lives of the World’s Most Famous Museum, is available from Grove.