The Life and Times of a True American Moral Hysteric

In which Anthony Comstock, Chronic Masturbator, Tries to Censor All the Mail in America

At an early age, Anthony Comstock felt he was destined for glory. As a child in New Canaan, Connecticut, he was enchanted when his mother read him stories from the Bible about saintly heroes battling satanic foes. Comstock never smoked. He shared a bottle of homemade wine with a friend one night, woke up with a violent hangover, and became a lifelong temperance advocate. Comstock later claimed that as an adolescent, he rid the area of a local saloon keeper, breaking into his establishment late at night, turning on the taps, and warning the barkeep in an anonymous note to leave New Canaan or else. But for all his professed virtue, Comstock’s own diaries reveal that he was also a chronic masturbator, which filled him with guilt and may have had much to do with his eventual calling as an anti-pornography crusader.

After his older brother Samuel died at Gettysburg, Comstock enlisted in the Union Army. Stationed in St. Augustine, Florida, Comstock tried to get the other soldiers to attend church with him. They didn’t appreciate his nagging and let him know, trashing his room in the barracks one night. Comstock tried to laugh it off, writing in his diary that “the boys” were giving him an initiation, even though he had been in St. Augustine for a year and perhaps it was a little late for that.

After the war, Comstock found a sales job at a dry goods store in New York, bought a house in Brooklyn, and married Margaret Hamilton, a minister’s daughter who was ten years older. They had one child, a daughter who died soon after her birth. Comstock found solace in a new crusade. As Comstock told it, a fellow employee at the dry goods store became afflicted with a sexually transmitted disease after developing an interest in erotic literature. Comstock went to the bookstore where his friend made his purchases, bought some illicit reading material, and returned with a police captain who arrested the dealer.

Newspapers picked up the story of the valiant dry goods salesman. One columnist suggested cheekily that if Comstock wanted to prove himself as a purification agent, he should visit St. Ann’s Street, where vendors openly hawked such books. Comstock invited a reporter to join him this time, collaring several more smut dealers and earning more glowing coverage. After that, he grew more ambitious. He figured out that a handful of publishers produced a total of 169 sexually explicit books available in New York. He believed that if he put them out of business, the supply of obscenity would dry up. William Hayes, a Brooklyn surgeon, was the most prolific of them; he took his life when he learned of Comstock’s interest. Comstock tried to purchase the late doctor’s printing plates from his wife so he could dissolve them in acid at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute. The widow wanted $650. Comstock didn’t have that kind of money, but he knew where to find it.

He wrote to the New York YMCA asking for the funds. Morris Jesup intercepted the letter and was so moved that he wrote Comstock a check for $650 and installed him as the secretary of the YMCA’s newly formed Committee for the Suppression of Vice. Within a year, Comstock seized more than twelve tons of offensive literature, and 200,000 salacious items including photographs, rings, knives, song-lyric sheets, playing cards, and what he referred to as “obscene and immoral rubber articles.” He kept his collection at the American Tract Society Building on Nassau Street in lower Manhattan, where it could do no harm. But even with the money and imprimatur of the YMCA, Comstock didn’t always succeed in putting smut merchants behind bars. It was the era of Boss Tweed, and the city was a lawless place. Pornographers bribed prosecutors to drop the charges against them. Corrupt state judges tossed out cases against booksellers and rubber goods dealers.

Comstock didn’t get very far when he attempted to have his adversaries prosecuted under the federal postal law. He jailed the early suffragette sisters Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee Claflin for publishing details about a prominent minister’s liaison with a married woman in their newspaper and mailing it to subscribers. But a federal jury acquitted the two women after the judge explained that the law made no mention of newspapers. The triumphant sisters mocked Comstock in their paper. “From Maine to California, we believe the new order of Protestant Jesuits called the YMCA is dubbed with the well-merited title of the American Inquisition,” they wrote. “We do not mean by this to assert that its leaders are like those of the Spanish institution of the same character. We should no more think of comparing Comstock . . . with Torquemada, than of contrasting a living skunk with a dead lion.”

So in February 1873, Comstock asked Jesup to send him to Washington to plead for a more stringent federal postal law. Jesup bought him a ticket and Comstock boarded the train with an assortment of offensive items from his trove. Congress was in turmoil. Republican president and Civil War hero Ulysses S. Grant had recently won a second term by a wide margin, trouncing his Democratic opponent, newspaper publisher Horace Greeley. But Democrats were attacking members of Grant’s administration, including Schuyler Colfax, his vice president, for accepting bribes from a bank underwriting the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad.

Despite the scandal, or perhaps because of it, Republican leaders gave Comstock an enthusiastic welcome. Colfax allowed Comstock to set up an exhibit of his unspeakable wares in his Senate office. Comstock pleaded with members of the House and Senate to pass a stronger antiobscenity law that banned offensive newspapers, along with mention therein of contraception and abortion, from the mail. “All were very much excited and declared themselves ready to give me any law I might ask for, if only it was within the bounds of the Constitution,” Comstock wrote in his diary.

William Strong, a U.S. Supreme Court justice, who had tried without success to insert the word “God” into the Constitution, helped Comstock craft a proper bill. Colfax promised that it would be passed before the end of the legislative session; Comstock stuck around Washington to make sure it did. He attended a reception at the White House where he shook President Grant’s hand and gazed disapprovingly at the female guests. “They were brazen—dressed extremely silly—enameled faces and powdered hair—low dresses—hair most ridiculous and altogether most extremely disgusting to every lover of pure, noble, modest woman,” Comstock scoffed. “How can we respect them? They disgrace our land and yet consider themselves ladies.”

Comstock’s bill cleared both the Senate and the House post office committees, but newspaper publishers complained that it threatened the freedom of the press and it was sent back to committee for amendments. Comstock worried that it might die there. House Speaker James Blaine told him not to worry; he would get it through before the end of the lame-duck session. Comstock stayed in the House past midnight on the final night. He waited as Blaine called for votes on hundreds of bills, but the speaker made no mention of his.

It was now early Sunday morning. Comstock felt compelled to abide by his mother’s wish that he keep the Sabbath holy and he departed for his hotel, walking through chilly darkness full of rage. How could God have so forsaken him? Lying in bed, Comstock began to doubt his faith and could feel Satan in his hotel room, tempting him to abandon it. “The Devil seemed determined to claim me as his servant.” he wrote in his diary. “He tempted me and made my heart rebellious. Yet a stronger hand was over me. I felt oh so crushed, so broken down, so tempted to sin against God. . . . O I felt almost like distrusting God, doubting and rebellious and then I went to bed, to pass the night beset by the Devil.”

Comstock awoke exhausted and, assuming that he had lost his congressional battle, attended church. He didn’t learn until early afternoon that the House had passed the antiobscenity bill at 2 am. The Senate blessed it, and on March 3, 1873, President Grant signed what would become known as the Comstock law. There was more good news for Comstock. His admirers in Washington had persuaded John Creswell, Grant’s postmaster general, to appoint him as a special agent in charge of enforcing the antiobscenity act. Comstock readily accepted the position, but he refused a government salary, saying the YMCA would take care of him financially. “I do not want any fat office created, whereby the Government is taxed or for some politician to have in a year or two,” he wrote. “Give me the authority that such an office confers and thus enable me to more effectually do this work and the salary and honors may go to the winds.”

Three days after the passage of the Comstock law, its namesake placed his hand on the Bible and swore to uphold his country’s postal laws. He received an inspector’s badge and a train pass entitling him to travel anywhere in the nation by rail, free, in pursuit of those who besmirched the mails. The Post Office now employed 63 special agents, but Comstock enjoyed an exclusive status. He didn’t have to audit post offices; he was free to focus all his considerable energies on exciting investigative work. He targeted people who used the mail to peddle fake medicines and fraudulent financial schemes. Comstock is credited with shutting down the many so-called state lotteries that used the postal system to sell tickets, most notably the popular Louisiana lottery, whose leaders attempted to bribe Comstock with a generous donation to his society if he left them alone. Comstock politely declined the offer.

But Comstock was best known for his antiobscenity cases. Within a year of the Comstock law’s enactment, he made 55 arrests under the new law, and he had a scar on his face from an encounter with a knife-wielding pornographer in Newark, New Jersey, whom he still managed to subdue, showing that he wasn’t someone to trifle with. “The mail of the United States is the great thoroughfare of communication leading up into all our homes, schools and colleges,” Comstock wrote. “It is the most powerful agent to assist this nefarious business, because it goes everywhere and is secret. It surely needs no argument here to convince the most exacting of all decent men, that no department of Government should be prostituted to serve this infamous traffic, nor become party to it, by continuing to serve these loathsome creatures after the character of their hellish business . . . is known.”

No matter what Comstock did, the newspapers knew about it and generally lavished him with praise, though not everybody approved of his grandstanding. The YMCA thought the special agent attracted too much attention to the vice trade and severed its ties with his society. Comstock was happy to be free of the Y; he suspected that its leaders were jealous of him. He reconstituted his organization as the independent New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Jesup remained on the board along with J. Pierpont Morgan, the powerful financier, and toothpaste magnate Samuel Colgate. Comstock encouraged the founding of satellite societies around the country. R. W. McAfee, another special postal agent, presided over the Western Society for the Suppression of Vice, with branches in Cincinnati, Chicago, and St. Louis. Thanks to the efforts of Comstock and his followers, states around the country enacted their own versions of the Comstock law.

By 1877, Comstock had largely shut down the obscenity trade. That year, the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice lamented in its annual report that there would be fewer front-page seizures of pornographic goods. The vice business had fallen on hard times. But Comstock still needed to make arrests so that his financial backers would continue to underwrite the society’s annual $10,000 budget. He went hunting for new forms of obscenity, harassing the publishers of medical volumes with anatomical studies of the human body and importers of European art books with nude portraits. Comstock also became the scourge of freethinkers who championed sexual liberation in Victorian America.

* * * *

Ezra Heywood was a radical contrarian. A handsome, dark-haired graduate of Brown University, he was a staunch abolitionist, but refused to fight in the Civil War because of his strong pacifist beliefs. He insisted that marriage was unfair to women, calling it “legalized prostitution.” Yet Heywood enjoyed a happy union to his wife Angela. Ezra and Angela, who lived in Princeton, Massachusetts, published the Word, a newspaper devoted to free love and labor reform. They were also among the founders of the New England Free Love League.

In 1876, Heywood published a turgidly written pamphlet entitled Cupid’s Yokes, in which he assailed marriage and exalted sex in pseudoscientific terms. Heywood also lambasted Comstock, calling him “a religion-monomaniac” and advocating the repeal of the Comstock law, which he called “the National Gag-Law.” Cupid’s Yokes was no fun to read and probably would have been quickly forgotten if it hadn’t attracted the interest of Comstock himself. Posing as “E. Edgewell of Squan Village, N.J.,” Comstock ordered a copy of the pamphlet from Heywood through the mail along with Trall’s Sexual Physiology, a book by a noted hydrotherapist. Once he received them, Comstock obtained a warrant for Heywood’s arrest from a Boston magistrate. He didn’t have to go to Princeton to serve it. Heywood was in Boston presiding over a meeting of the Free Love League.

Comstock gave a colorful account of what transpired in his book, Traps for the Young. When he arrived at the meeting, he found the Heywoods onstage in front of an audience of several hundred supporters. Angela Heywood delivered an impassioned speech in which she defended free love and assailed Comstock. Comstock left the building and stood outside on the sidewalk. “The fresh air was never more refreshing,” Comstock wrote. “I resolved to stop that exhibition of nastiness, if possible. I looked for a policeman. As usual, none was to be found when wanted. Then I sought light and help from above. I prayed for strength to do my duty, and that I might have success. I knew God was able to help me. Every manly instinct cried out against my turning my back on this horde of lust. I determined to try. I resolved that one man in America at least should enter a protest.”

Having fortified himself with such self-aggrandizing rhetoric, Comstock went back inside and endured more blasphemy. Just when he thought he could take no more, Ezra Heywood left the stage and wandered into the lobby. This was Comstock’s chance. He followed Heywood and confronted him. “I have a warrant for your arrest for sending obscene matter through the mail,” Comstock informed him. “You are my prisoner.”

According to Comstock’s account, Heywood made several attempts to escape. He told the special postal agent that he needed to inform the crowd that he was in police custody and would be departing sooner than scheduled, but Comstock would have none of that. Heywood next asked the vice suppressor if he would get his hat and coat. Comstock told a doorman to retrieve them. The doorman returned with Angela Heywood, who wanted to escort her husband to jail. Comstock had no interest in sharing a carriage with Mrs. Heywood. “I felt obliged out of respect to my wife, sister, and lady friends to decline the kind offer of her (select) company,” he wrote. Heywood’s supporters realized something was wrong and hurried to the lobby to see what it was. Comstock rushed his captive out of the building and shoved him into a carriage, ordering the driver to take them to the Charles Street jail. “Thus, reader,” Comstock boasted, “the devil’s trapper was trapped.”

Heywood offered a terser version of his arrest. “In Boston,” he wrote, “as I had momentarily left the chair in which I was presiding over a public convention to transact business in an anteroom, a stranger sprang upon me, and refusing to read a warrant, or even give his name, hurried me into a hack, drove swiftly through the streets, on a dark, rainy night, and lodged me in jail as a ‘US prisoner.’” Heywood didn’t discover until the next morning when his jailers finally showed him the warrant that it was Comstock himself who had arrested him. “Knowing the purity of my life and writings, the severely chaste objects and methods of my work, I scorn even to defend myself from ‘obscenity’ against the mercenary assassin of liberty!” Heywood raged.

United States District Court Judge Daniel Clark tried the case in 1878. Heywood’s supporters filled the courtroom in Boston but Clark refused to let them testify about Heywood’s character. He shut down the defense’s efforts to call witnesses who would challenge the government’s contention that Cupid’s Yokes and Sexual Physiology were obscene. Clark wouldn’t even permit the books to be read in the courtroom. He only gave the jurors copies with the objectionable parts underlined when they left the courtroom to deliberate. The jury didn’t find Sexual Physiology indecent, but it accepted the government’s contention that Cupid’s Yokes was. Clark sentenced Heywood to two years of hard labor in Dedham jail in Massachusetts.

Comstock was elated. “Another class of publications issued by Freelovers and Freethinkers is in a fair way of being stamped out,” he boasted in the Society’s annual report. “The public generally can scarcely be aware of the extent that blasphemy and filth commingled have found vent through these varied channels. Under a plausible pretense, men who raise a howl about ‘free press, free speech,’ etc., ruthlessly trample under foot the most sacred things, breaking down the altars of religion, bursting asunder the ties of home, and seeking to overthrow every social restraint.”

After the verdict, thousands of Heywood’s supporters gathered for an “indignation meeting” at Boston’s Faneuil Hall to condemn Comstock and the Post Office Department. Some contended that the special agent should confiscate the Bible, which overflowed with sex. Others insisted that Comstock was violating the sanctity of the mail by sending letters under false names to entrap people and opening packages that weren’t addressed to him. “The two ways specially sanctioned by this learned judge are the post-office decoy system and the post-office espionage system,” said Theodore Wakeman, a prominent Boston attorney. “Two plainer violations of the Bill of Rights—two meaner outrages upon liberty, decency, and morality—have never been perpetrated among our people! The learned judge did not invent them; they are old instruments of the Christian Inquisition. . . . Is this not a libel on our age and century, or have the Dark Ages returned?”

Heywood’s admirers appealed to President Rutherford Hayes to pardon Heywood. Hayes didn’t think it was a crime for a United States citizen to advocate the abolition of marriage. Nor did he find Cupid’s Yokes to be “obscene, lascivious, lewd, or corrupting in the criminal sense.” Comstock tried to change the president’s mind, but it was no use. After six months in jail, Comstock’s “devil trapper” walked out of Dedham jail a free man.

This seemed like an opportune time for freethinkers to lobby Congress to rescind the Comstock law. They collected more than 70,000 signatures and packed a hearing before the House of Representatives on the law. Comstock thought Satan’s army had descended on the nation’s capitol. “As I entered the committee room,” he wrote. “I found it crowded with long-haired men and short-haired women, there to defend obscene publications, abortion implements, and other incentives to crime by repealing the laws. I heard their hiss and curse as I passed through them. I saw their sneers and their looks of derision and contempt.” But neither the House nor the Senate wanted to overturn the antiobscenity law and face the wrath of Comstock and his followers around the country.

Comstock kept a watchful eye on Heywood, who had grown bolder since his presidential pardon. In the fall of 1882, Comstock pretended to be “J. A. Mattock of Nyack-on-the-Hudson, N.Y.” and placed an order for Cupid’s Yokes, an edition of the Word with Walt Whitman poems from Leaves of Grass, and another containing the offending advertisement for a birth control device mischievously called the Comstock Syringe. A grand jury indicted Heywood, claiming that Cupid’s Yokes and the Whitman poems were “too grossly obscene and lewd to be placed on the records of the court.” Even Whitman thought the publisher of the Word had gone too far. “Heywood is certainly a champion jackass,” the poet wrote to a friend. “I am sorry for him, but his bed is his own making, and he should have known what Comstock would do to him. . . . I only hope we shall escape the consequences that follow.”

This time, Heywood found himself in front of T. L. Nelson, a U.S. District Court judge less inclined to defer to Comstock. Nelson threw out the charge involving the Whitman poems, saying that neither was “grossly obscene and lewd.” He ridiculed the charge related to Cupid’s Yokes. “The court is robust enough to stand anything in that book,” Nelson said. In the end, Heywood stood trial on a single count: advertising the Comstock Syringe. He took the witness stand and delivered a four-and-a-half-hour lecture, comparing himself to Jesus and John Brown and accusing Comstock of persecuting him because he advocated the repeal of the postal obscenity law.

The jury deliberated for two hours and found Heywood not guilty. The jurors said they would have acquitted him sooner, but they were entitled to one more free lunch courtesy of the federal justice system. When they heard the verdict, Heywood’s friends in the courtroom cheered and embraced each other. Comstock sat among them, trying to contain his fury. “Upon the release of their Chief Free-lover, or more properly free-luster, what did the Liberals do?” he wrote. “How did they receive the man they helped release from the penalties of the law? THEY HAD A PARTY.”

It was a rare defeat for Comstock, who continued for three more decades to arrest people for mailing literature that he found offensive. In 1892, a Post Office official acknowledged that the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice “has been so closely identified with the postal department that it is almost a part of it.” But after the turn of the century, the public grew less prudish. Judges found Comstock’s cases specious. Publishers and theatrical promoters welcomed his condemnations because they invariably translated into higher sales of tickets and books. The Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw coined the word “Comstockery” to describe the postal inspector’s inability to distinguish between art and smut. “Europe likes to hear of such things,” Shaw said. “It confirms the deep-seated conviction of the old world that America is a provincial place, a second-rate country town civilization after all.”

Comstock responded with appropriate cluelessness. “George Bernard Shaw?” he told the New York Times. “Who is he? I have never heard of him in my life. Never saw one of his books so he can’t be much.”

The vice suppressor spent his final days pursuing Margaret Sanger, future founder of Planned Parenthood, who fled the country in 1914 after a federal grand jury indicted her for violating the Comstock law by mailing copies of the Woman Rebel, her monthly publication. Sanger argued that the founding fathers would have been aghast if they could have seen Comstock’s abuses of the Post Office. “When the Constitution of the United States authorized Congress to establish post offices and post roads, it was not intended that the authority should go beyond this,” she wrote. “It did not authorize it to censor the matter to be conveyed, nor to sit in judgment upon the moral, or intellectual qualities of the printed matter or parcel entrusted to it to deliver. The post office was, primarily, a mechanical institution, not an ethical one, whose business was efficiency, not religion or morality.”

After he died the following year, Comstock became a laughingstock, ridiculed by F. Scott Fitzgerald and H. L. Mencken. But the Post Office would carry on his legacy for many more years. Postal inspectors could still effectively censor books and magazines by banning them from the mail and showed the same inability to distinguish between literature and smut, between a D. H. Lawrence and a Larry Flynt. It would take a humiliating defeat in federal court to finally convince them to stop trying.

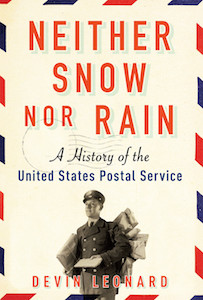

Excerpted from NEITHER SNOW NOR RAIN. Used with permission of Grove Press. Copyright © 2016 by Devin Leonard.

Devin Leonard

Devin Leonard is a staff writer at Bloomberg Businessweek. Previously a senior writer at Fortune and a staff writer for the New York Observer, he has also written for the New York Times, New York, Wired, and many other publications.