It was around this time that my mother had a terrible accident. Well, as it was happening it didn’t seem so terrible, but it turned out that it was. She went out to lunch with a couple of ladies from the retirement community where she lives, and they were stepping off a curb to cross the street when one of them lost her footing and began to fall. She knocked into my mother, and my mom tipped over too. She broke her fall with her right arm and fractured her wrist. She also bruised her hip. They put a cast on her, but after a few days, her hip really started to bother her. They gave her some pain meds. She was hobbling around for quite a while. It turned out they’d missed another fracture in her right hip, and because of the way she was favoring that side, she ended up bearing the weight on the left side and eventually fractured her coccyx just by walking off-kilter. That’s when the pain got unbearable. She’s eighty-five.

This makes her sound fragile, and I guess physically she was, but temperamentally she’s the kind of person she herself would characterize as a “tough old bat.” She was really pissed off, for example, at the other old lady who fell on her (having broken her fall on my mom, she emerged from the episode without a scratch). My mother’s cantankerous, a smoker, and a realist. She’s also a lefty, a feminist, an atheist, and a right-to-die activist. Her refrigerator magnets say: “Intelligent Design: Helping Stupid People Feel Smart Since 1987,” and “My Life. My Death. My Choice.” That’s why it threw us all for a loop when she got hurt—not the injury itself (after all, she was old, and these things happen), but the way she responded. She really couldn’t handle the pain. I went to visit her at the hospital in Ohio. Her doctor had recommended she stay in the hospital for a while. She could get out of bed to use the bathroom and so on, but she had to use a walker and mostly remain lying down until the fractures healed. She was moaning quite a bit and dozing off, probably partly because of the pain meds. When she’d wake up, she’d sometimes make some acerbic remark about the incompetence of the nursing staff or of that lady that fell on her, but sometimes she’d be in so much pain she’d just get a glassy look in her eyes and say, “Help me. Help me.”

My older sister, Carolyn, lives much closer than I do—about a two-hour drive away—and my mother had long ago given her medical power of attorney just in case something like this were to happen. She also gave my sister detailed instructions about her dnr paperwork. Carolyn had been driving down regularly and helping our mother through the crisis. She’d been great. I felt a little useless by comparison, but while I was there I tried to contribute what I had to offer, which mostly consisted of stroking our mother’s arm or hip or forehead and saying, “There, there.” I also read aloud to her, some stories from the New Yorker, but she’d fall asleep after the first paragraph or so. Her doctor seemed to think she was going to heal, but she looked really broken in her adjustable bed, lying there, just moaning like that. Help me, help me.

I wrote Sami about it after I got home, because he knew what that kind of pain was like. I told him, “I had a beautiful dream last night about my mother dying. In my dream, she’d had enough, she wanted to go, so she rented some kind of magical, quiet flying machines for herself and me and two other women. One must have been for my sister, but I didn’t see her. Anyway, we were on these things that were sort of like children’s swings, just flying silently over the ocean, with the night sky. The moon was full, and the stars were out, and just as we were over a placid, beautiful smooth part of the ocean, my mother felt it was time. She arched her back over her swing, and her body looked young and beautiful—it looked like my body. And then she let herself fall toward the ocean, and as she fell I called out to her, and I knew she heard it: ‘I love you,’ just as I always say just before we hang up the phone. And I was so glad she heard it, and that was the end. I wish it could be exactly like that.”

Well, as I reproduce that message I see that there are a couple of things that may appear unseemly, the main one being the suggestion that my mother’s death could be a relief. But perhaps you’ll understand it, given my mother’s preoccupation with making a graceful exit. At the time, it was hard to imagine she would heal, even though the doctor said she would. She’d broken her bones with her own weight. It was very difficult to watch her in pain like that. It probably also seems a little weird that I described my body as “young and beautiful.” Well, that’s embarrassing. But one of the things I liked about talking to Sami was that his Asperger’s meant he didn’t really play by the rules of social decorum. He would just say things without beating around the bush, like that he knew that he was gifted at music and sex, and he was terrible at hugging, and he was highly intelligent and socially inept. In explaining the fact that he’d managed to have a love life despite his extreme social awkwardness, he said, “Well, I’m relatively good–looking, maybe that helped.” That was probably a bit of false modesty, in fact, but it gestured toward the obvious. So it seemed natural to respond with similar candor.

For some reason, I guess a combination of dancing, genetic disposition, and all that moderation, my body hasn’t really changed much since I was a girl. After my pregnancy, my belly button migrated about half an inch south. My right breast has a little dent in it from a surgical biopsy I had a few years ago (benign), but you can’t really see the scar. My mother lost her whole right breast when she was younger than me. Her cancer metastasized, but she’s been in remission for many years, and now that’s the least of her worries. My hands in the hand dance sort of looked like my body—I mean, they moved the same way. I’m quite sure that the image of my mother’s youthful body arching back gracefully like that came from the gesture in the hand dance. I wished I could give her that.

In the same message in which I told Sami about the dream, I also mentioned that my friend Arto had sent me an article about a pickpocket. “He doesn’t actually steal for a living,” I said. “He’s a conceptual artist or a performance artist. He tells people this is what he does, and he always gives back the things he takes. He’s a magician, but it’s more complicated than that. He says of the people he steals from, ‘My goal isn’t to hurt them or to bewilder them with a puzzle but to challenge their maps of reality.’ This is interesting. Anyway, I wondered why Arto was sending me this article, and I thought it might have something to do with dance, and how I talk about things being dance that don’t necessarily look like dance.”

I quoted more from the article—a bit where the guy spoke about shaking people’s hands. He said he applied a very delicate pressure on the insides of their wrists with his index and middle fingers and then “led” them a bit, the way a salsa dancer would do. He did this to see if they would follow his lead. That apparently makes a person a good mark. He said he was a “choreographer” of people’s attention, and he couldn’t even explain exactly how he picked up on cues—that it was a neurological peculiarity of his. I wrote, “It’s interesting, isn’t it? And then I also wondered if Arto sent it to me because of that line about not wanting to hurt the people he steals from, and the fact that the guy tells people he’s going to take something from them, and then he gives it back. That’s a little like me, the way I tell people that I may take things from them and put them in my art, but if they don’t want me to, I won’t, and I’ll always give it back to them, maybe it will even be a little more precious. That’s like me and you. I also did that to Arto. You’re kind of irresistible to a pickpocket like me. You have so many precious things in your pockets. :)”

I wasn’t just talking about choreographing a dance to Sami’s Paganini. I had already told him I thought I wanted to write him into a novel.

A minute after I sent that message I thought, “Uh-oh.” I broke my own rule and wrote a second message that day—a very short one: “After I sent you that last message, I thought, ‘Hmm, maybe it’s not such a good idea to joke with a paranoid person about picking their pockets!’ I’m not really a pickpocket! I just take inspiration from you. But I’ll give it back if you want it.” He said he wasn’t worried. He wrote, “I think I know the feeling when someone steals something from you. It’s not what you do.” Still, I keep asking him if it’s ok for me to write about certain things. Later, I began asking Tye as well.

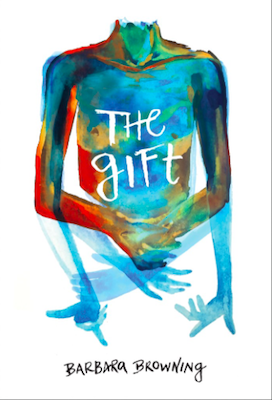

From The Gift. Used with permission of Emily Books. Copyright © 2017 by Barbara Browning.