The Evolution of the Great Gay Novel

From Homer to Larry Kramer

The Atlantic recently pronounced Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, which was released in March, the Great Gay Novel. Writer Garth Greenwell called the book, which follows four men (three of them not straight) over three decades of friendship, “the most ambitious chronicle of the social and emotional lives of gay men to have emerged for many years.” While Yanagihara’s realistic and comprehensive depiction of gay lives is certainly a milestone in LGBT literature, it’s important to remember the great gay writing of the past. In times when homosexuality was regarded as deviant—and even a crime—authors boldly published works about same-sex love. Behold: Literary Hub’s timeline of writing about the lives of queer men and women.

In The Iliad, Homer describes Ganymede, a Trojan hero frequently referenced in Greek mythology, as “handsomest of mortals, whom the gods/caught up to pour out drink for Zeus and live/amid immortals for his beauty’s sake.” In one version of this myth, Zeus, smitten by Ganymede’s beauty, takes the form of an eagle and abducts the young boy. Zeus then brings him to Olympus, where he serves as Zeus’s cup-bearer. The mythological relationship between Zeus and Ganymede, later depicted by Ovid, was the model for the ancient Greek practice of paiderastia, the socially acknowledged erotic relationship between an adult man and an adolescent boy.

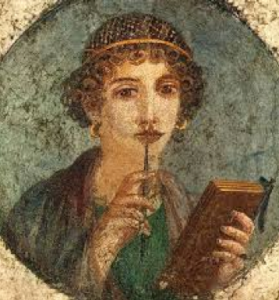

In “Sappho 31,” the ancient Greek poet, who was often referred to simply as “The Poetess,” depicts a wedding scene. The poem, addressed to the bride, begins with a flattering description of the groom (“Peer of the gods he seems to me”). However, the author’s true feelings toward the marriage soon become clear as she goes on to illustrate her strong desire for the bride: “Your image silences me. / My tongue becomes thick / and in my flesh moves an impalpable fire.” The author then reveals her jealousy of the man who will spend the rest of his life with the woman she loves.

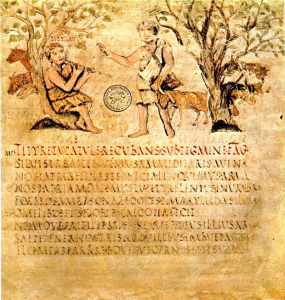

In the second of Virgil’s Eclogues, a shepherd named Corydon proclaims his love for a boy named Alexis, which is so intense that it tortures him. “Cruel Alexis,” Corydon asks, “heed you not my songs? / Have you no pity? You’ll drive me to my death.” Sadly for Corydon, who at one point boasts about the length of his pipe, Alexis doesn’t seem to share the sentiment.

Antonio Rocco’s Alcibiades the Schoolboy, initially published anonymously, is a defense of homosexual sodomy modeled after a traditional Platonic dialogue. The work depicts a teacher in ancient Athens who uses philosophy, logic, and ancient texts to convince one of his students to have sex with him. The teacher makes the convincing argument that it would be an insult to nature to use sexual organs for their intended purpose and refutes biblical denouncements of homosexuality. The text, notorious for its sexual explicitness, has been considered by many to be the first gay novel.

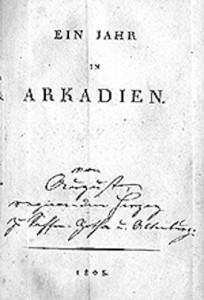

A Year in Arcadia: Kyllenion is a novel by Duke Augustus of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg set in ancient Greece. The novel follows several different couples, including a gay male couple, as they fall in love and begin their lives together. It has been noted as “the earliest known novel that centers on an explicitly male-male love affair.” A Year in Arcadia’s classical setting, along with the Romantic movement’s encouragement of communicative and tender male friendships, prevented this novel from causing a stir among German aristocracy. However, Duke Augustus was later criticized for writing characters who “stepped over the bounds of manly affection into unseemly eroticism.”

In 1870, Bayard Taylor published Joseph and His Friend: A Story in Pennsylvania, widely considered to be the first American gay novel. The novel, dedicated to those “who believe in the truth and tenderness of man’s love for man, as of man’s love for woman,” tells the story a young farmer named Joseph Aster who marries a wealthy woman before falling in love with his close friend. The novel also helped plant the seeds of the gay rights movement of the latter half of the 20th century. In one scene, Philip argues for the rights of people “who cannot shape themselves according to the commonplace pattern of society.”

In Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, the artist Basil Hallward becomes enthralled by the beauty of Dorian Gray, the young man who is the subject of a portrait he has recently painted. Through Basil, Dorian meets Lord Henry Wotton, a hedonistic dandy who believes that beauty is the only thing worth pursuing. Under Wotton’s influence, Dorian adopts a pleasure-seeking lifestyle and attempts to preserve his youth. Prior to the novel’s publication in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, the magazine’s editor J.M. Stoddart told its publisher George Lippincott that “in its present condition there are a number of things that an innocent woman would make an exception to,” namely, the novel’s blatant homoeroticism. Stoddart’s prediction was correct; the magazine edition of Dorian Grey caused so much controversy that copies were swiftly removed from newsstands. Wilde, who would later be put on trial twice for sodomy, removed references to homosexuality in the 1891 book edition.

Explicitly gay themes began to emerge in the literature of the early 20th century, though many authors who published such material did so under pseudonyms. In André Gide’s 1902 novel, The Immoralist, a newlywed recovering from tuberculosis on his honeymoon in Tunis rediscovers his zest for life when he becomes sexually attracted to a series of Arab boys. Edward Prime-Stevenson’s Imre: A Memorandum (1906) follows the romance between a British aristocrat and a Hungarian military officer. Death in Venice, Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella, relates an aging writer’s infatuation with a young Polish boy. E.M. Forster, closeted from the public for his entire career, privately wrote Maurice, a novel about a young man discovering his homosexuality. It was published in 1971, after Forster’s death, and was lauded for its representation of “a refreshingly unapologetic young gay man who was not an effete Oscar Wilde aristocrat, but rather a working class, masculine, ordinary guy.” Gertrude Stein’s experimental 1914 work Tender Buttons has been widely interpreted as an exploration of lesbian themes and specifically Stein’s relationship with Alice B. Toklas.

Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar is a coming-of-age novel centered on Jim Willard, a young man who discovers his homosexuality around the time of World War II. Prior to the book’s publication, an editor at EP Dutton told Vidal, “You will never be forgiven for this book. Twenty years from now you will still be attacked for it.” The New York Times refused to advertise The City and the Pillar, and the controversy surrounding the novel forced Vidal to publish under pseudonyms for a period.

Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt depicts a romance between Therese, a department store salesgirl, and Carol, a woman going through a divorce. When Carol’s soon-to-be-ex husband begins to suspect her homosexuality, he hires a private investigator to spy on Carol and Therese. The Price of Salt, which Highsmith published under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, has long been considered among the first works of gay fiction to have a happy ending and has been praised for its defiance of lesbian stereotypes.

The post-Stonewall period saw a rise in explicitly gay literature, with gay and lesbian authors drawing upon their own experiences in LGBT communities. Rubyfruit Jungle, Rita Mae Brown’s debut novel from 1973, is an autobiographical coming-of-age and coming out story about Molly Bolt, the adopted daughter of a poor family who at a young age discovers her attraction to girls. As Molly works to overcome the difficult circumstances of her upbringing, she discovers her identity through a series of relationships with young women. Larry Kramer’s Faggots (1978) portrays New York’s gay community in the brief moment just after gay liberation and just before the AIDS crisis. The semi-autobiographical novel portrays protagonist Fred Lemish’s disillusionment with gay subculture.

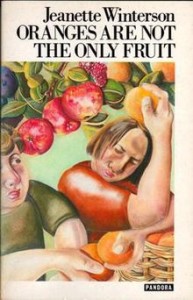

The coming-of-age story was reinvented as the coming out story in the 1980s and 1990s, with gay novels heavily featuring teenage and young adult protagonists. Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (1985) is a semi-autobiographical novel depicting the upbringing of a lesbian girl named Jeanette in an English Pentecostal community. When the religious community discovers that Jeanette is in a relationship with another girl, the two are subjected to exorcisms. Michael Chabon’s debut novel, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh (1988), follows Art, a recent college graduate, as he develops an attraction to a gay man named Arthur and realizes his bisexuality.

Rebecca Brill

Rebecca Brill is a writer who lives and studies in Minneapolis. Her work has appeared in The Paris Review Daily, Broadly, Lilith, and elsewhere.