The Dream of 2011 is Dead: Portlandia Comes to an End

Like the "Hipster" Itself, the IFC Sketch Comedy Has Become a Kind of Relic

Ephemerality is often a feature of art, not a bug. But the immediacy of a work, the way it clicks perfectly into the viewer’s world and context at the moment of its release, can become the exact reason it’s impossible to engage with years later—at least not without a certain feeling of involuntary revulsion. (“Was that really what everyone was into?” Yep!) Television, which is written and produced on notoriously-tight schedules and frequently brought into existence explicitly based on fads, experiences this at light-speeds. And long-running series like Portlandia, the IFC sketch show created by comedian Fred Armisen and Sleater-Kinney guitarist and vocalist Carrie Brownstein, have the rare opportunity to become artifacts while they’re still on the air.

Portlandia, which began its eighth and final season this month, will end its run at 77 episodes; not enough for the classic syndication goal of 100, but certainly enough to make up a hefty body of work. There’s far less variation in quality than you might expect for an eight-year series. Its most recognizable characters and catchphrases—Candace and Toni, the owners of parodic feminist bookstore Women and Women First; “put a bird on it”; Kyle MacLachlan’s earnest, reggae-head mayor—are all firmly established in the first season and don’t change much.

That’s thematically appropriate, since the entire premise of Portlandia is that Portland itself never changes, or hasn’t, at least, for 20 years. The show’s first episode begins with “The Dream of the 90s,”’ a music video in which Armisen plays Jason, a man who has just returned from his brief visit to Portland—where ’90s culture is alive and well—evangelizing about the city to his friend Melanie (Brownstein), a former clown who now walks her dog in Ugg boots and a velour tracksuit. “The Dream of the ’90s” is dedicated to a time when people were simultaneously “getting tribal tattoos,” “singing about saving the planet,” and “content to be unambitious.” It depicts a parallel world where Al Gore won the 2000 election and there was no Bush administration.

What is this sketch—and the show it spawned—actually nostalgic for? Though it feints at skewering this worldview, Portlandia ultimately posits the past as a place you can go in order to reshape the present, a historicized version of the world where you could safely assume that everything was fine—that the ’90s could be picked back up and used as a fashion statement, like a pair of gauges or Doc Martens. This is echoed even in the show’s theme song: Washed Out’s “Feel It All Around,” a hazy, sun-kissed standout in the subgenre that came to be known as chillwave—itself notable for repurposing signifiers from the 1980s. Though most of the artists lumped into the subgenre are still making music, in chillwave land (as in Portlandia) it is forever 2011. Is there a better way of capturing confusion about misspent political energy, the dream of not having to do anything, than turning the past into a breakfast buffet? Portlandia’s attitude toward history is like a distilled version of the (rather unfunny) joke of a protestor at the Women’s March complaining that she could be at brunch (and not marching) if Hillary Clinton had won the presidential election. (Portlandia’s second-season finale tracks a several-hour wait for a brunch establishment, followed by an entire “Brunch Special.”)

The best jokes of Portlandia came from this tension between Portland’s slacker image, a city “where young people go to retire,” and the show’s characters caring way too much about their hide-and-seek leagues, the uniforms of their police force, and their Battlestar Galactica binge sessions. The very first sketch of the series after “Dream of the ’90s” mocks characters Peter and Nance for being overly invested in the chicken they want order at dinner: where it comes from, what it ate, and whether or not it “pal-ed around” with other chickens. “Over,” another one of the show’s best early sketches, depicts the cycle of people attempting to be cool before slumping back into the comfortable arms of normie life, posturing in a delicate dance based on who likes what. It’s the perfect target for a show that also had a difficult time holding a static opinion on pretty much anything.

When Portlandia debuted, it was largely praised as a light-hearted, ultimately gentle spoof of Portlanders’ lifestyles. New York Times TV critic James Poniewozik, then at TIME, called Portlandia an “eccentric, surprising little microbrew of a show.” Noting that the series aired on IFC—the network associated with the film center and theater—he wrote that it was “a comedy for people who watch IFC, about people who would watch IFC (if they owned televisions), on IFC.” Much of the praise relied on the authenticity and goodwill Portlandia had bought with Brownstein’s genuine Pacific Northwest credentials. In 2011, Katie Carter, co-director of In Other Words, the bookstore used as a filming location for Women and Women First, said, “I think we were expecting some negative feedback, but there have only been a few comments like, ‘Why would you let them make fun of feminism?’ But Carrie Brownstein’s a feminist, and it’s meant to be tongue-in-cheek.”

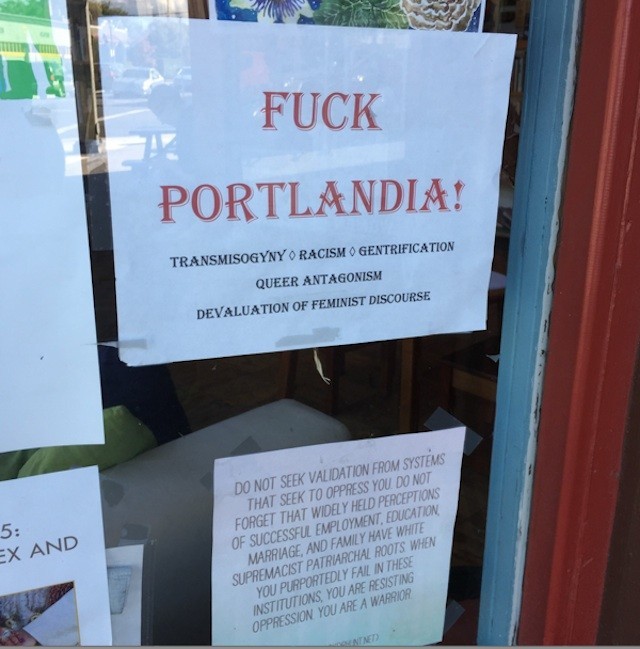

But in 2016, the store, now under new leadership, publicly ended its relationship with Portlandia, in a statement that criticized the show for being “trans-antagonistic” and “trans-misogynistic” due to Armisen’s penchant for putting on dresses to play female characters. They also criticized the production for asking the store to remove a sign in support of Black Lives Matter and blamed the series for speeding up gentrification in the city. The statement—and the sign in the window that prompted it—was titled simply, “Fuck Portlandia.” (Related: Part of the oddness of Portlandia’s final season is the specter of Armisen’s semi-public reputation as a dirtbag; watching the show since the emergence of visible consequences for powerful men in Hollywood who engage in sexual violence feels like waiting for the other shoe to drop.) To track this shift in the public reaction to Portlandia is to watch the very concept of ahistoricity itself become a target.

The sign posted outside of feminist bookstore In Other Words in 2016.

The sign posted outside of feminist bookstore In Other Words in 2016.

The most generous counterargument you could make in the face of In Other Words’ complaints—Armisen dressing up as a woman, Armisen and Brownstein playing at being Korean teen girls, a sketch where Armisen plays a “quirkily” neurotic stripper unaware of office etiquette—would rely heavily on the show’s commitment surrealism, its willingness to be completely absurd as a way of suspending any obligation to reality, one that generally contains a cultural sensitivity clause. But even if that were justifiable for a moment, seven years ago, it isn’t anymore. And many of Portlandia’s riffs on an alleged counterculture have by now been totally assimilated by the mainstream.

The intentionally out of touch style of the women in the background of “Dream of the ’90s” video is almost identical to the “adorkable” Zooey Deschanel on New Girl—a show that premiered the same year as Portlandia, and was aimed at a much larger, broader audience, without the flattering injoke quality. By 2014, McDonald’s had become the kind of place Peter and Nance might feel comfortable eating when the chain announced its commitment to “Our food. Your questions.” (Unfortunately, none of the questions were about the names of the cows.) It’s the nature of subcultures to eat themselves, and eventually be subsumed in a form that is palatable to the boring and powerful. Jerry Seinfeld thinks Portlandia is one of the best comedies of all time.

The first four episodes of Portlandia’s eighth season are prime evidence of the way the show, and its viewpoint, have become curiously out of sync. One sketch in the season’s first episode follows a team of people making Forgotten America, a prestige true-crime podcast produced in real-time, actively trying to manipulate police in order to present them as being uninterested in doing their jobs. The jokes about S-Town and the omnipresence of Blue Apron advertising are funny enough, but the episode glosses over the suggestion that the podcast is a replacement for the police officers’ body cameras. (Funny!) Another sketch finds a couple who see a van for sale and imagine the possibility of abandoning their lives to “chase light,” only for the fantasy to inevitably collapse into rage, roadside peeing, and the eventual dissolution of their marriage. They decide to get a condo instead.

Carrie Brownstein and Fred Armisen in Portlandia‘s “Forgotten America” Sketch

Carrie Brownstein and Fred Armisen in Portlandia‘s “Forgotten America” Sketch

Like the prototypical “hipster,” itself a term that used to carry cultural force before being strip-mined of coherence, the characters on Portlandia have largely “grown up”—by closing off the possibility of really changing their lives or anyone else’s. (The police are the protagonists of the Forgotten America sketch.) The premiere’s throughline tracks a band of aging men played by Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic, Fugazi drummer Brendan Canty, and Black Flag vocalist, voice actor, and generally loveable obnoxious human Henry Rollins—Brownstein’s contemporaries—who have all gotten real jobs and accepted their limited ability to make the world a better place. To watch Portlandia in its eighth season is to watch a show that’s come to the conclusion that this absorption process is not only inevitable, it’s actually good.

It’s bitterly funny that Portlandia begins with a dream of what was possible in the 1990s, and ends when so many of the its cultural debates have reared their heads again. In just the last few weeks, provocateurs like Katie Roiphe and Andrew Sullivan have loudly re-emerged into the public sphere, like lumbering monsters you thought had been defeated at the end of an old film. Affirmative consent seems like a novel concept that some people are happy to debate in the public sphere, but it was originally raised as a goal in the ’90s. Will & Grace, Roseanne, and Full House, are back on the air, with Mad About You, Charmed, and Murphy Brown soon to follow. The dream of the ’90s may be alive in Portland, but the nightmare of the ’90s is alive everywhere—and the dream of 2011 is, for all intents and purposes, long dead.

Eric Thurm

Eric Thurm is a writer in Brooklyn whose work currently appears in The Guardian, The New Republic, GQ, and Esquire. He is the creator and host of the event series Drunk Education (formerly known as Drunk TED Talks).