I flew economy on an MD-88 to Panama City in the rainy season. In this season, in the crooked intercontinental arm of Central America, the rain doesn’t have an On and Off switch but only gradations of soft and brutal. Green is the dominion color here: the city is surrounded on all sides by stalled sea and jungle. And the real green, of course, is the reason for the nation’s existence: the swamp-green money, collected and counted and flowing all hours through the world’s most famous shortcut. The Canal passes through the city like a knife through a ghost. It seemed, after a few post-collegiate years struggling in the nonprofit sector, a good place to start a career in business.

My father arranged the assistant’s job at the Panama headquarters of Kitterin Inc., but there was no special treatment for the vice president’s son besides that solitary penny-loafer in the door. I was given a cubicle in a windowless office in one of the dust-green high-rises of the New City. My boss was an efficient, chinless executive who preferred to speak to me in English although I responded in Spanish to bolster my conversational skills. Her only individualizing traits were the two Harvard diplomas hanging in her office and the ritual reading of her horoscope in the mornings before the numbers came in from the factory. My job was specific and deadening: check the daily manufacture totals of 2.5 oz., 4 oz., and 6 oz. baby-food jars in its various flavors and varieties; oversee the weekly export shipping docket to North, Central, and South American suppliers; “liaise” via e-mail with jar, label, and package wholesalers (the jars were imported from Venezuela, and for that first month the parent company shifted almost daily from private to national ownership, wreaking havoc on the export price of glass). All of these responsibilities were actually conducted by corporate higher-ups; I was merely a second or third set of eyes, scanning for irregularities. When I missed aberrational spikes and dips, a computer program caught them and I was given a human-oversight warning. For the first month that I worked at Kitterin I never touched a single jar of baby food. However, the office was decorated with giant headshots of white, chubby babies, their lips twisted in digestive satisfaction and their eyes staring hungrily into your heart. Even the bathrooms with their automatic-flush urinals and automatic hand dryers weren’t safe from these ravening eyes and ecstatic mouths. I had a joke—“baby brother is watching”—but I had no one to tell it to.

“Kitterin Baby Food®, made from the finest natural ingredients, organic and nutritious, tested on tiny taste buds, mom approved.” It was a billion-dollar conglomerate. It fed the diapered future. The Spanish commercial showed a mom piloting a spoon of goop onto the pink landing strip of an infant’s mouth.

I stayed in an eerily nondescript long-lease motel called the Royal Decameron Arms. It was located in the New City five blocks from the Kitterin offices and it shared a parking lot with a KFC. The room’s walls were mint, its curtains sage, its heavy-breathing air conditioner the only new amenity. On my first day, the elderly American who ran the establishment gave me a map of the city with parts of the southern half x-ed out in red. “Red is for red zone,” he informed me. “That means if you so much as walk those streets you’re liable to be shot on sight.” They were gang-owned, drug- and poverty-ridden, and rumor had it morgue vans cleared dead bodies off the streets with more regularity than garbage pickup.

“I thought the country was stable and prospering,” I said to the landlord, who wore a hunter-green u.s. army T-shirt.

“It is stable, and it is prospering, because it leaves the gangs alone. The last time the government interceded, Noriega became the leading drug trafficker in the Western Hemisphere. The day the government disperses the gangs is the day corruption starts. Don’t worry. The rest of the city is as safe as a retirement home.”

I kept to the un-x-ed areas of his map, wandering the rainy streets and admiring the sad Spanish haciendas with gated gardens pruned by teams of laborers. Catholic churches sang on Sunday with their wooden doors ajar. Occasionally I taxied out to the ruins of old forts and pirate prisons, the moss invading the stones as the jungle tried to reclaim its stolen ground. Every time I took a cab in Panama City, the first question the driver asked me was “when are you leaving?” The drivers would strike their palms together and let the top palm glide away like a plane. I knew they wanted the fare to the airport, but it became a constant chorus. When are you leaving? What time is your flight? When will you go?

At night I usually stayed in my room, masturbating to my computer. It’s odd to travel so far to perform the same whipping ritual alone in a rented room—porn sites become as familiar as family photo albums. There she is again, that girl, as memorable now as a distant cousin, with the black bob and shamrock tattoo; she’s switched private schools again, her pleated jumper plaid instead of navy; same manicurist though, French tips. Those were the most fulfilling ten seconds of my day, my body seizing, my mouth a volcano, my fist slowing in the aquatic glow of the monitor. Once a week I’d eat dinner with my father’s only Panamanian friends at their mansion in the posh San Francisco district. They owned the national airline and told stories of the night in December 1989 when the United States invaded, how the American soldiers appeared at their gates in the fog of dawn, and how the couple brought food and drinks out for them. The soldiers only accepted cans of soda, as they were forbidden to consume anything unsealed. “In case we might be poisoning them,” the wife told me. “I took down their names and phone numbers and called their families for them back in the States. We all cried that morning, me for my country and those parents for their sons.”

I had the sense that real events were still taking place in Panama, just not in the parts that I knew. It was the same feeling that must befall those curious pockets of the United States that don’t observe daylight savings—time moving peculiarly all around them, jumping forward and back, shifting and reacclimating, while their own clocks ticked on, dull and untouched. I had no plans to continue my career in food manufacturing, no intention of remaining at Kitterin longer than the minimum six months I’d pledged my father. I was lonelier in my cubicle than I was jacking off at night or drinking rum in an American ex-pat bar located next to the national airline’s travel agency. My few sexual encounters—a shipping inspector from Gothenburg; a Texas grad student documenting the migration of surfers along the western isthmus— ended on my sage bedsheets with me repeating the taxi refrain. When are you leaving? What time is your flight?

Never underestimate the catalytic power of boredom. We put so much faith in the role of chance—the barely caught subway on which one’s future wife sat reading last week’s New Yorker; the yellow light, which resulted in a family of five crushed in the intersection. But boredom is the archangel of afternoon suicides and Craigslist affairs. Boredom places our heads in ovens, pushes us between stranger’s legs, makes hobbies out of pharmacy aisles, and, if left untreated, turns solid floors into swamps of quicksand. Chance exonerates us, but boredom reveals us—the little flaws flower, urges itch.

Marisela Nuñez appeared one Monday morning in the cubicle bank of Kitterin like a Goth babysitter determined to stick to an un-desirable job. She was an intern in our department and a fourth-year economics student at the university. Her hair was dyed fuchsia—an eccentricity that would have deterred me in New York—and her eye-lids were so wide she looked permanently frightened. I explained spreadsheet procedures and invited her out to lunch. We sat under the rain-beaten umbrella of an outdoor KFC table, picking at deep-fried animal bones. “I thought you’d like food from your home country,” she said. I decided our affair wouldn’t extend beyond Panamanian borders. With twenty minutes remaining in our lunch break, we crossed the parking lot and had what I still consider one of the best sexual experiences of my life. Marisela single-handedly rendered my cherished porn sites irrelevant. Her breasts were wobbly teapots with long, impractical stems. My body was also a discovery for her. “I’ve never seen orange there before,” she said, pointing to my pubic hair. We had sex standing, against two mint walls. After that first encounter, Marisela returned to the office first, me following five minutes behind, and the weekly shipping dockets took on a magical allure.

After three dates, I went with her to visit her family. Marisela said she was “middle class,” but that term didn’t carry the same over-broad designation that it does in the States nor the same promise of dependable comforts. She drove twenty minutes out of the city, into the muddy, humid outskirts where dogs and naked children ran across diarrhea-brown roads. Palm trees waved their fronds in stranded roadside emergency. Her tan Honda lacked the ordinary luxury of shock absorbers. “There are two classes of untouchables in Panama,” she told me. “The poor and the rich. You never touch either if you live by honest means.” There was a strangled sense in this visit of a lesson being taught. She pulled up in front of a single-story house painted the same color as her hair. It had fresh aluminum siding, indigo stained-glass windows, a covered above-ground pool, and a vegetable garden teeming with an exploded war chest of children’s toys. Inside were many tidy linoleum-tiled rooms with plastic-wrapped sofas and plastic nosegays. If there was a lesson, it was one sweetened with kindness. I met her father—a moist, gentle hugger and the owner of a nearby mechanic shop—and her three younger brothers (her mother was away in the north visiting her sister). We ate goat stew and drank beer and I watched her brothers in the backyard perform endless choreographed dances. The rain abated for the afternoon, and neighbors drifted over, adding their radios and trays of ice to the picnic table. I was neither a curiosity nor an intruder, just another set of hands clapping to her eldest brother’s impressive somersaults.

Marisela observed my enjoyment. “This must be different from what you’re used to,” she said.

“Yes,” I said. “We don’t have anything like this in New York.” “Like this,” she repeated sarcastically and began to clear the dishes with vicious efficiency. I had passed her test by failing it, and while the Nuñez family seemed like the warm cultural entente I had been seeking in Panama, I decided right then to discontinue my daily post-KFC fuck-fests with their daughter on our lunch breaks.

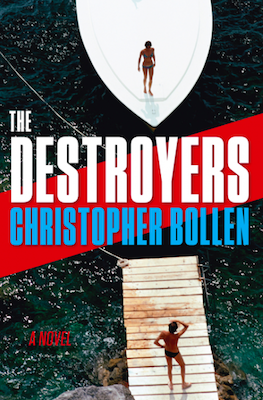

From The Destroyers. Used with permission of Harper. Copyright © 2017 by Christopher Bollen.