The Brutal Murder of Mary Grace, Peacock

Love and Death on Flannery’s Farm

The peacocks of Andalusia have had a brutal year. At the beginning of 2015 the aviary at the Milledgeville, Georgia dairy farm where Flannery O’Connor wrote and lived out the end of her short life, the aviary on the side of Andalusia sheltered three shimmering birds, all named after characters in O’Connor’s short stories from a public poll. Manley Pointer, the lone male of the ostentation, was christened after the villainous fake Bible salesman in “Good Country People.” The two female birds were Joy/Hulga, named after the woman whose wooden leg Pointer steals, and Mary Grace, the hostile teenager in “Revelation.” Now, only Joy/Hulga remains.

“When I came on board, we started seeing Manley fail,” said Andalusia Farm’s executive director, Elizabeth Wylie. She started at Andalusia in fall last year as the successor to Andalusia’s longtime director Craig Amason. In late December, she noticed Manley Pointer was ailing. “He was sluggish and not eating. He’s a peacock, so we’re used to seeing him strutting around, and we noticed he was sitting down a lot.” On January 8, April Moon Carlson, the operations and visitors service manager, arrived in the morning to see Manley struggling. As a friend drove them to the vet, Manley Pointer died in her arms. He was 6 years old.

Andalusia held a sunset funeral to honor Manley Pointer. They buried the bird on the grounds of the farm as mourners read from Flannery O’Connor’s work. The Bitter Southerner sent retired Atlanta Journal-Constitution obituary writer Kay Powell to cover the event. “Tail feathers shed after his last mating season were collected into a huge bouquet,” Powell wrote. “A freshly washed feather was presented to each mourner, and one was laid on the grave.”

When Flannery O’Connor brought the first peacocks and peahens to Andalusia farm in 1952, mail-ordered from the Florida Market Bulletin at $65, she had never seen or heard a peacock. She had returned to Georgia from Connecticut after being diagnosed with lupus, the hereditary autoimmune disease that would ultimately end her life at age 39, forced to relinquish a promising academic career up North. The peafowl were a way to cheer herself up, and a signal that she intended to settle there for good. O’Connor had always been entranced by birds. In Savannah, where O’Connor was born and lived with her family until age 13, she kept chicken in the backyard as pets. As a five-year-old, she attracted the attention of British newsreel company Pathe after she taught a chicken to walk backwards. She sewed tiny wardrobes for her feathered pets, insisting on bringing a chicken named Aloysius, outfitted in a bow tie and jacket, to her Girl Scout meetings.

“When I first uncrated these birds, in my frenzy I said ‘I want so many of them that every time I go out the door, I’ll run into one,’” O’Connor wrote in her essay “The King of Birds.” It was not long before she got her wish. Andalusia, then a working dairy farm crowded by cattle and farmhands, was soon dotted by dozens of peacocks. They nested in the trees and wrought havoc with the shrubberies, destroying the roses and figs and emitting their startling caws at great volume. At their peak, there were around 40 peafowl strutting around the red Georgia clay.

“I have tried imagining that the single peacock I see before me is the only one I have, but then one comes to join him; another flies off the roof; four or five crash out of the crepe-myrtle hedge; from the pond one screams and from the barn I hear the dairyman denouncing another that has got into the cow-feed,” O’Connor wrote. “My kin are given to such phrases as ‘let’s face it.’”

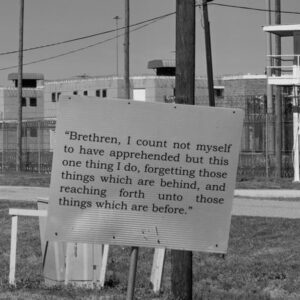

The peacocks ran wild on the property until O’Connor’s death in 1964. They became a recurring theme in O’Connor’s work and somewhat symbolic of the author herself: her ability to find the oddity in beauty, the beauty in the odd. In “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” O’Connor describes Lucynell Carter, a deaf girl pawned off by her elderly mother to a handyman, as having “long, pink-gold hair and eyes as blue as a peacock’s neck.” The birds represented that mixture of the glorious and the grotesque that so appealed to O’Connor. Famously, O’Connor’s guiding principles for writing were to “make your vision apparent by shock—to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large and startling figures.” The peafowl at Andalusia, both large and startling, seemed a concrete reminder of that approach.

O’Connor’s mother Regina gave away many of the peacocks, donating the ostentation to a monastery, a state park, and a nearby hospice. For a time, Andalusia was abandoned. The farmhouse laid empty, the pasture emptied of cows and dairy equipment. It wasn’t uncommon for local teenagers and literary pilgrims to sneak past the “No Trespassing” gate to take a look at the grounds. When Mississippi police found the body of Confederacy of Dunces novelist John Kennedy Toole after his suicide, they found evidence that one of his last stops had been to Milledgeville to see Andalusia. Alice Walker, who had grown up in nearby Eatonton, wrote about visiting the grounds with her mother and discussing the peacocks. “Those things will sure eat up your flowers,” Walker quoted her mother saying. “Yes,” she replied. “But they’re a lot prettier than they’d be if any human had made them, which is why this lady liked them.”

Andalusia opened as a museum in 2003. Peacocks returned to the property in 2009, a gift from Col. Charles Ennis of Milledgeville. They lived in the aviary to protect from predators, and served as a major attraction to visitors and the children of Milledgeville. “Unfailingly they’re just a big attraction,” said Andalusia’ director Elizabeth Wylie. “Families and kids come to see them. The peacock is so identified with Flannery. Quite often, April and I would lock the gate [to the front drive] and got back and watch the peacocks. It’s calming to watch them.”

But the aviary did not serve as much protection for Mary Grace, the second of Andalusia’s peacocks to die this year. One morning, Wylie noted, the peacocks’ caretaker came in to see an unusual number of feathers scattered all over the pen, and a hole in the wiring. “Mary Grace had been savagely murdered,” Wylie said. “I saw ‘murdered’ because the creature, we think a weasel, didn’t eat her. There were body parts all over. The creature ate her face. That’s one of the characteristics of a weasel, is it eats the face. ”

The lone remaining peacock, Joy/Hulga, escaped with her life but not, Wylie suspects, without some trauma. “Of course, she must have witnessed all that.” Wylie said. “I just can’t imagine. It does have a Flannery flair to it.”

It’s not the only recent event that seems to have a tinge of O’Connor’s love of the macabre. “There’s rumors here that there’s a ghost donkey on the property,” Wylie said. The O’Connor’s beloved donkey, Flossie, had died several years ago. But hunters on the property say they hear an old donkey braying. “One guy who told me that, his eyes got as big as saucers,” Wylie said. But perhaps the atmosphere of the house itself has something to do with it. “He sits in those hunter’s blinds and read Flannery on his Kindle,” Wylie added.

Wylie and Carlson are now searching for new birds to replace Manley Pointer and Mary Grace, but are rethinking Andalusia’s strategy for sheltering them. Ideally, peacocks would have much more space than the aviary affords them. “There are different issues that arise if you have a caged bird, not to be so metaphorical,” Wylie said. “This is a lesson in having a living collection. We’re a museum, so we have the non-living collection—Flannery’s bed and her crucifix, all the farm tools and implements. But there’s also a living collection, all the flora and fauna on the property. We have deer and foxes and turkey. We’ve seen bobcat tracks. I think the cautionary tale is for nonprofits and museums who take on the task of caring for live animals.”

Still, the wildness of Andalusia—more than 500 acres preserved in the middle of Milledgeville’s car dealerships and big box stores—is very much part of its charm. Classes from the Georgia State College and University come not just for the site’s literary heritage, but for its sampling of Georgia’s native plants and animals. Under her tenure, Wylie has worked to make the farm attractive to people with a vast array of interests. There’s currently an exhibit on O’Connor’s fashion on display, and a bluegrass festival planned for the grounds in early October. The artist Tim Youd is re-typing one of O’Connor’s works on the grounds as part of his project to type out one hundred classic novels at places connected with the author’s life. In 2016, Andalusia will host a bird festival, something that seems very much in accordance with O’Connor’s interests.

In the meantime, Wylie hopes to bring at least one other peacock to the farm to fill out the aviary. And when they find him, she’s already settled on a name. “We’ll call him Manley Pointer II,” she laughed.

Margaret Eby

Margaret Eby has written for the New York Times, The New Yorker, the Paris Review Daily, Bookforum, Salon, Slate, and the Los Angeles Times. Originally from Birmingham, Alabama, she now lives in New York City.