The American Artist Who's Been Drawing Interwar Berlin for 23 Years

Comics Creator Jason Lutes on a Project That's Spanned Half his Life

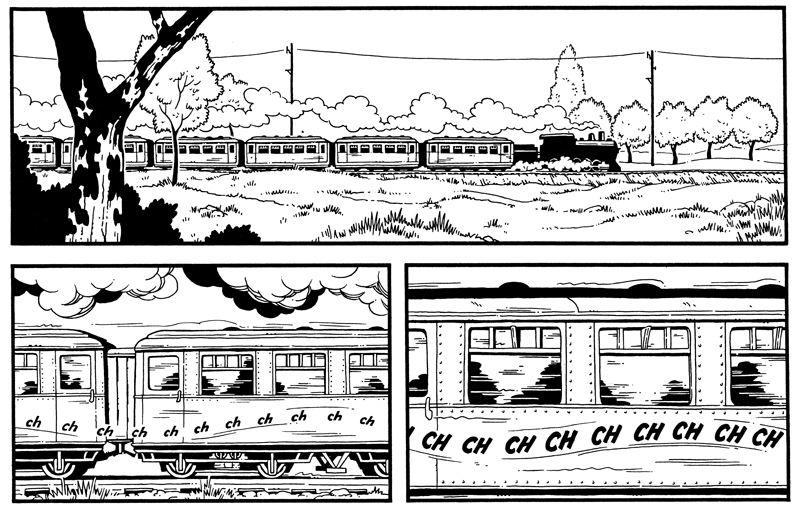

The first time Jason Lutes visited Berlin, in 2000, he expected to see crowded tenements and gray cobblestone streets. Instead, through the windows of a speeding train, he saw green trees, brown spires, and blue skies. “My first thought was, oh my god, it’s in color,” he says. “In all the photographs I’d ever looked at, it was in black and white.”

Lutes was drawing a series of comic books called Berlin, about daily life during the rise of fascism. He’d assembled thousands of reference images: rooftops and railroad tracks, soldiers and shopkeepers, spectacles and streetcars. But until that day, he had never seen Berlin up close. “Here it was, in the light of the sunset,” Lutes says. “I had never imagined that the city that I’d studied for so long would actually strike me as beautiful.”

This year, almost a quarter-century after Lutes started the series, he will send the final chapter to his publisher. What began as an esoteric obsession, a fictional journey into the annals of history, suddenly seems timely. Berlin taught Lutes what fascism looks like—and although he knew he’d find it in old books and black-and-white photographs, he didn’t expect to see anything like it in his own country.

Berlin owes its existence to an advertisement in The Nation. In the mid-90s, Lutes was flipping through the magazine and spotted a paragraph about a book of photographs of Germany between the wars. “In that moment of just reading the ad copy, I decided that my next comic book was going to be about Berlin in the 20s and 30s,” says Lutes, who now teaches comics at the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont. “And it was going to be 600 pages long.”

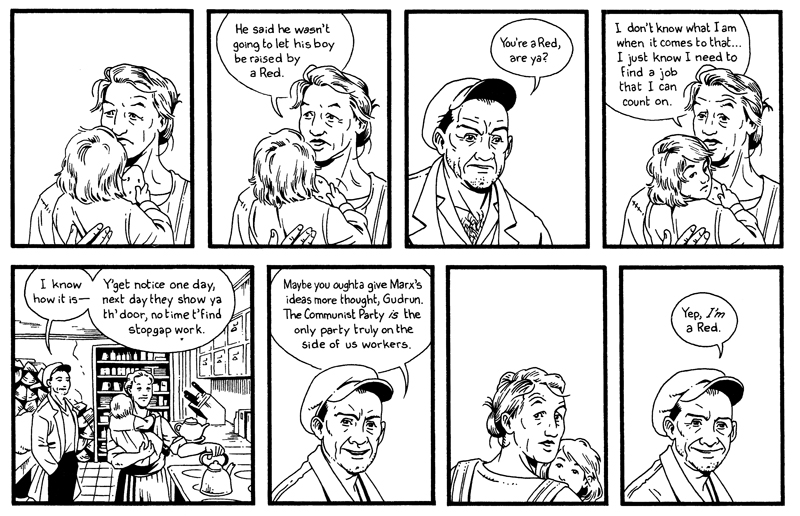

Lutes spent two years collecting photographs and reading German history before he began to draw. In the opening volume of Berlin, set in 1928, a cynical journalist named Kurt Severing meets a young art student named Marthe Müller. He writes, she draws: together they embody the elements of comics. Soon the cast of characters grows. A working-class mother joins the Communist Party, a young man enlists in the Hitler Youth, a Jewish family sells antiques and struggles to stay safe. They inhabit a huge, humming city—a metropolis on the cutting-edge of science and art, but also on the crumbling foundations of a weak democracy.

From Berlin: Book One by Jason Lutes, via Drawn & Quarterly

From Berlin: Book One by Jason Lutes, via Drawn & Quarterly

Daily life is too loud, in these early chapters, for the characters to make out the martial beat of fascism. We follow Marthe through crowded city squares and smoky jazz clubs. Gudrun, the working-class mother, joins huge worker protests. There is still room for hope in each character’s future.

At the end of the third chapter, Kurt sits in front of his typewriter, imagining the millions of words that pile up in Berlin’s dozens of newspapers. “It makes me think of drowning, but I want to be able to see it another way,” he thinks. “Instead, human history as a great river, finding its course along the lowest points in the landscape, and each page as a stone.” He can see the city out his window.

“If each stone is placed carefully and with purpose, perhaps something can be built,” he continues. “Not to dam the current, but to divert its course.”

*

Lutes, who is 49, wears glasses and a zip-up hoodie. He works out of his basement in rural Vermont, and while he talks about his childhood, his young son and daughter—both of whom like to draw comics—run around upstairs.

He spent the first decade of his life in the mountains of western Montana, in a house that he describes as “on the edge of the civilized world.” As a kid, Lutes found four-panel newspaper comics boring, but a tobacco shop in Missoula fed his love for superheroes and westerns. He would look up at shelves of comic books, wondering which to spend his allowance on. “It was like being in a candy shop,” he says. “This cornucopia of visuals.”

Drawing came quickly to Lutes, though his obsession with Berlin did not. He learned to draw before he could write. “I would literally just copy entire pages out of various comic books I had lying around,” he says. His mother helped: “She would write in the words for me.” At the time, Lutes knew little about World War II—only what he glimpsed on TV.

That changed when, in a high school history class, he watched a video about concentration camps. “The main image I retained from it was a bulldozer pushing piles of bodies, piles of emaciated corpses, into trenches,” Lutes says. He remembers feeling horrified, then asking himself: “What was that?” Though he’d heard about the Holocaust before, seeing it struck him in a different way. “I think in the time since then, I’ve been trying to make sense of that,” Lutes says.

At first, Lutes pushed the video out of his mind. But more than a decade later, after he started drawing Berlin, he realized that it had driven his obsession with the city: He wanted to understand what comes before calamity. “It’s the period before story that generates the storm,” he says. “What’s it like before this horrible thing happens? Before all hell breaks loose and the world goes south?”

From Berlin: Book One by Jason Lutes, via Drawn & Quarterly

From Berlin: Book One by Jason Lutes, via Drawn & Quarterly

Answering that question was difficult, as history tends to record calamity rather than calm. In the 90s, before the ubiquity of Google Images, Lutes was able to track down images of Berlin’s famous churches and wartime ruins, but he struggled to find images of factory workers, university students, train conductors. “Usually, when we’re looking at the past visually, the pictures we get are the postcard pictures of famous landmarks and famous people.”

Lutes decided to avoid postcard pictures whenever he could. Instead, he adopted an eccentric research method: he restricted himself to sources contemporary to the period he was interested in, staying away from books and photographs that came after the Nazi Party took power in 1933. “To imagine what life was like for people at the time, I wanted to really limit my understanding of what came later,” Lutes says. He skipped Charlie Chaplin’s landmark film The Great Dictator and avoided Downfall, a famously dark film about Hitler’s last days. He was trying to turn his lack of knowledge into an advantage, by refusing to look at Berlin in hindsight, through the dark haze thrown up by a decade of totalitarianism. He asks the same of his readers, by omitting charged symbols like the swastika for most of the series.

Years of staring at old photos trained his eye. In his basement studio in Vermont, where an old map of Berlin hangs on the wall, Lutes pulls out a photograph titled Kohlenträger, or “coal-carrier,” taken by August Sander in 1929. It shows a man in a shabby three-piece suit, carrying a wicker basket of coal. Lutes points out a thin piece of cloth that the man has knotted and slung over his shoulder, to help him bear the weight. “When you draw something, you’re learning about it,” he says.

Lutes shows off his keen eye in the structure of his drawings. When a character dies, we see the world from ground level, fading in each frame until only a gaping white hole remains. When someone closes a door in the bottom-right frame, the next page opens on a new room. “The page is a door,” he says.

*

For all his painstaking research, the distance between Lutes and his subject can leave him vulnerable to critique. He speaks no German, spent his childhood far from cities and even farther from Europe, and grew up sheltered from war. For years, he drew Berlin from afar—until a German publisher finally invited him to visit.

“I became terrified,” Lutes says of that first trip. He worried that his work of historical fiction would, in Germany, seem like mere fiction. He imagined German readers asking: “Who is this American kid from the suburbs who’s going to tell us our history?”

He worried, too, that his imagination would buckle under the weight of the real Berlin. “Every cartoonist is a control freak, to one degree or another, because what we do is put words and pictures into little boxes all day,” he says. “I felt like if I went there, the reality of it I would find paralyzing.”

Berlin did astonish Lutes, but it did not paralyze him. Some German readers pointed out factual errors, like street signs copied incorrectly. He was asked, politely, why he felt he could bring to life a story he had not lived. On the other hand, several younger Germans thanked him for illustrating an era often shrouded in silence.

“The Berlin that Lutes designs is certainly an artistic construction, culturally and temporally distant from its subject,” wrote Ekkehard Knörer, in a mostly warm review for the Berlin newspaper Tageszeitung. “However, the Berlin of the late 20s and early 30s is also a foreign world for its present inhabitants. Lutes deliberately chooses the precise point when the city is transformed from a laboratory of modernity to a laboratory of catastrophe.” The comic Berlin is a laboratory, too. Its chapters are an experiment in historical memory—proof, perhaps, that characters who never lived can bring a real city to life.

At moments when his imagination failed him, Lutes looked for echoes of the past in the world around him. In 1999, he was living in Seattle, struggling to draw labor protests that, in 1930, had left several Berliners dead. But then, tens of thousands of demonstrators began to gather in downtown Seattle in protest of the World Trade Organization. Lutes realized that these protesters were a modern equivalent of the anti-capitalist movement in Berlin.

“At home in my drawing studio, I was working on my book, and imagining the lives of these people,” Lutes said. “And I could actually ride my bike downtown and be one of them.” One day, protesters dressed in black walked through downtown, breaking windows, while a group of peaceful protesters begged them to stop. Lutes was watching a social movement start to splinter, just as leftist movements had splintered in Nazi Germany.

This year, Lutes believes, the parallels have grown much stronger. When Donald Trump called for a ban on Muslim immigrants to the US and blamed Mexican immigrants for crime and unemployment, it reminded Lutes of the way Nazis scapegoated Jews in the thirties. “Here’s basically somebody who’s positing himself as a strong man who will bring us all together—spouting a lot of the same rhetoric that any strong man throughout history has spouted, including Hitler,” Lutes says. In Berlin, nationalists attack a family of German Jews and vandalize their store.In recent months, swastikas have been found on American churches and subways. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, hate crimes have increased since Trump’s election, and Americans from Washington to Oregon to Kansas have targeted immigrants with vitriol and violence.

At the same time, Lutes felt that after spending 23 years on the project, he couldn’t give in to the temptation to turn his comic into an allegory for the Trump era. “I still plan to stay true to the characters and their context, without letting current events color things in any overt way,” he says of the final chapters. For all the similarities between Berlin and the United States today, the present can seem in some ways unprecedented. “We’re in a place where reality feels like speculative fiction, which makes historical fiction like my book seem quaint.”

From Berlin: Book One by Jason Lutes, via Drawn & Quarterly

From Berlin: Book One by Jason Lutes, via Drawn & Quarterly

Lutes has been working on Berlin for almost half his life, and virtually all of his working life. Visually, the style of the series has changed little. But Lutes said that as the years passed, some of his loftier aims—like crafting a grand story about love, loss, and the power of comics—fell away. He learned to simply follow the characters he had created. “My original plan was to get the whole thing done by the time I turned 40,” he said; he turns 50 in December. Though he often gave in to restlessness and exhaustion by distracting himself with other projects, Lutes rarely let himself quit. “As long as it takes me to pursue that thread, I will continue to unravel it until I get to the end of it,” he said.

Berlin looks back at the past, but its characters look forward, toward the future. The first scene takes place in a train compartment. In one corner, a young nationalist snoozes in uniform; his time will come later. For now, Marthe, the artist, meets Kurt, the journalist, and together they gaze out at passing spires and smokestacks. They arrive in a city of possibility, a city where the future hasn’t happened yet. “I am anxious and excited as we emerge from the station,” Marthe writes in her diary. “Into the flow of it as into a river.”

Daniel A. Gross

Daniel A. Gross is a writer and public radio producer. He's written for The Washington Post, The Guardian, and the website of the New Yorker. His radio stories have aired on NPR's All Things Considered, Radiotopia's Criminal, and the BBC World Service. He tweets @readwriteradio.