Ten Great Books With Their Own Languages

A Brief Survey of Memorable Made-Up Dialect

In a “Note on Language” in The Wake, his debut novel just published in the US by Graywolf Press, Paul Kingsnorth argues that he doesn’t “get on with historical novels written in contemporary language.” The reason for this, he argues, is that fidelity to the language of a particular era allows readers to feel the distance of that period. This belief—debate its merits among yourselves—led Kingsnorth to compose The Wake in what he calls a “ghost language” that reflects, more or less accurately, the historical setting in which it takes place (England during the Norman Conquest). And so, for example, words of French origin that came over with the conquerors were excised from his characters’ vocabularies, spelling was altered, and Anglo-Saxon words were reintroduced:

loc it is well cnawan there is those wolde be tellan lies and those with only them selfs in mynd. there is those now who specs of us and what we done but who cnawan triewe no man cnawan triewe but i and what i tell i will tell as i sceolde and all that will be telt will be all the triewth. triewth there is lytel of now in this half broc land our folc wepan and gretan and biddan help from their crist who locs on in stillness saen naht as they weeps. and no triewth will thu hiere from the hore who claims he is our cyng or from his biscops or those who wolde be his men by spillan anglisc guttas on anglisc ground and claiman anglisc land their own

As this excerpt makes obvious, reading The Wake can initially be a daunting and disorienting experience. Although completely foreign vocabulary is relatively minor (a short glossary of these words offers clarity), even the words a reader knows often look odd on the page. I found myself reading aloud, sounding out the words until they made sense. After twenty or thirty pages, the language began to come more naturally and my sense of accomplishment was outweighed only by the growing tension of the plot.

Much of the discussion about the novel will focus on the novelty of this ghost language and though The Wake is rewarding enough to deserve attention for its many other merits, its unusual linguistic construction led me to think of other works that similarly inhabit languages unique to themselves, whether through dialect, an attempt at capturing the singular nature of consciousness, or in one case, unique because it is essentially alien.

Finnegans Wake, James Joyce (1939)

Joyce’s notoriously challenging novel can be considered the ur-text for the type of work listed here. Full of neologisms, portmanteaux, linguistic hybrids, and perhaps just a dash of nonsense, Finnegans Wake sets the standard for modernist literature.

I put hem behind the oasthouse, sagd Pukkelsen, tuning wound on the teller, appeased to the cue, that double dyode dealered, and he’s wallowing awash swill of the Tarra water. And it marinned down his gargantast trombsathletic like the marousers of the gulpstroom. The kersse of Wolafs on him, shitateyar, he sagd in the fornicular, and, at weare or not at weare, I’m sigen no stretcher, for I carsed his murhersson goat in trotthers with them newbuckle-noosers behigh in the fire behame in the oasthouse. Hops! sagd he.

Riddley Walker, Russell Hoban (1980)

There has been no shortage of post-apocalyptic fiction published in the past few years (see below), but one of the best novels in the genre was written nearly 40 years ago. Set two millennia after a nuclear war destroyed much of the world, Riddley Walker—inspired in part by the legend of Saint Eustace—imagines the world of the distant future as uncannily similar to that of the distant past. Like many of the examples included here, Hoban employs a language that reflects the shattered landscape:

I stood there and holding ready with my spear. Nothing like it never happent befor but it wer like it all ways ben there happening. The dog getting bigger bigger unner the grey sky and me waiting with the spear. It dint seam like the running brung him on tho he wer moving fas. It wer mor like he ben running for ever in 1 place not moving on jus getting bigger bigger til he wer big a nuff to be in front of me with his face all rinkelt back from his teef. Jus in that fraction of a minim the dogs face and the boars face from my naming day they flickert to gether with my dads face all smasht. I helt the spear and he run on to it. Lying there and kicking with his yeller eyes on me and I finisht him with my knife.

A Clockwork Orange, Anthony Burgess (1962)

Joyce’s masterpiece may be the greater book, but Burgess’s novel (owing much to Kubrick’s film adaptation) is arguably better-known, or at least quoted. No book on this list has infiltrated popular culture in the way A Clockwork Orange has. Indeed, many words in Nadsat, Burgess’s amalgam of Romany, Cockney rhyming slang, and a Russian-English hybrid lingo, have entered the lexicon.

The stereo was on and you got the idea that the singer’s goloss was moving from one part of the bar to another, flying up to the ceiling and then swooping down again and whizzing from wall to wall. It was Berti Laski rasping a real starry oldie called ‘You Blister My Paint’. One of the three ptitsas at the counter, the one with the green wig, kept pushing her belly out and pulling it in in time to what they called the music. I could feel the knives in the old moloko starting to prick, and now I was ready for a bit of twenty-to-one. So I yelped: ‘Out out out out!’ like a doggie, and then I cracked this veck who was sitting next to me and well away and burbling a horrorshow crack on the ooko or earhole, but he didn’t feel it and went on with his ‘Telephonic hardware and when the farfarculule gets rubadubdub’. He’d feel it all right when he came to, out of the land.

A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing, Eimear McBride (2014)

Perhaps any narrative filtered through stream of consciousness would qualify as being written in a language unique to itself, but in McBride’s hands, this novel about a troubled woman’s sexual awakening reaches an almost overwhelmingly singular register. Like the other work considered here, A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing teaches its reader how to read it:

So. This as well when no one looks. Go n’eiri an bother leat while the wind be always at your back. Run up the fields. Blink to the house. Go sun blindness. Turn my arse. Lift to fly. Balloon across the earth. Puff ball keep your knick-knacks covered. Belting on the wind me. Beating me at my own game. Scup there skirts and give us a dance. Be pelted by the dark rains. Feet wet like trough. Soak them blue to black through flesh and bone. Scratch my arms on fair blackthorn. Knee cut rocks for learning how to fly. Whip grass cut hands and lips on a scutch pipe. I’ll call all the fairies and ones living underground. For I know they’re listening. Will give me thorns in my pockets and thorn in my bed. I’ll jig on their houses til my lips turn red. I’ll give you a whirl twirl. A smack on the paddy whack but Get in this house. Get in this house you, always, always comes.

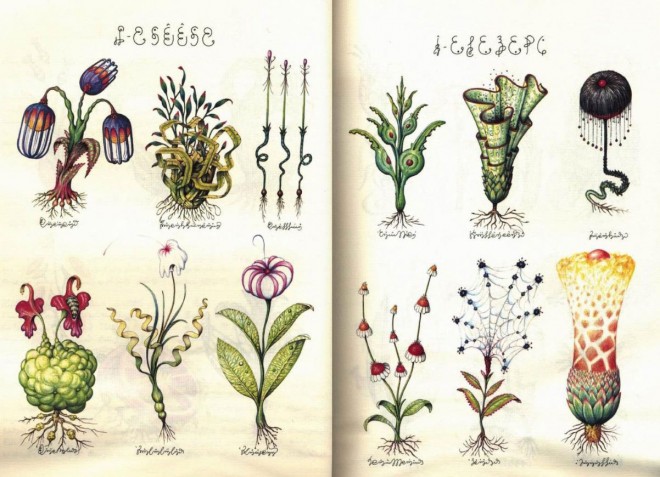

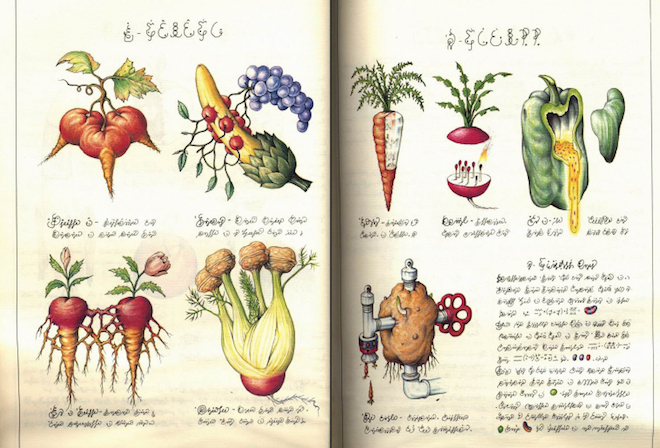

Codex Seraphianus, Luigi Serafini (1981)

The Codex is a bit of an outlier, being written in its own—invented—language as opposed to a variation on an existent language, but the book, presented as an encyclopedia of an alien world, is simply too weird and wonderful to pass over. It has been discussed at length elsewhere (I recommend Justin Taylor’s essay in The Believer), as has its even more mysterious precursor, The Voynich Manuscript, but just a glance at one of its bizarrely illustrated pages (below) will confound any reader.

Trainspotting, Irvine Welsh (1993)

Welsh’s famous novel follows in a noble line of literature composed partially in Scots’ dialect, including Wuthering Heights and some of James Kelman’s work, though Kelman rejects the term dialect as being elitist. Although visually opaque to many English readers, Trainspotting is, like The Wake, much clearer audibly. Read aloud the following excerpt, ideally with someone in earshot, as proof:

Ah sit frozen for a moment. But only a moment. Ah fall off the pan, ma knees splashing oantae the pishy flair. My jeans crumple tae the deck and greedily absorb the urine, but ah hardly notice. Ah roll up ma shirt sleeve and hesitate only briefly, glancing at ma scabby and occasionally weeping track marks, before plunging ma hands and forearms intae the brown water.

Sinking of the Odradek Stadium, Harry Mathews (1975)

Harry Mathews’s epistolary novel is comprised of the letters between husband and wife on all manner of subjects suitable to conjugal life… but mostly about a lost 16th-century treasure in Florida. Tro-tsi Twang Panattapam McCaltex (in case it’s not obvious, that’s the wife) writes in a language called Pan, through which Mathews, with the kind of humor we expect from a member of the Oulipo, lays a series of clues to the ultimate surprise ending:

Pan persns knwo base bal. The giappan-like trade-for mishn play with it in our capatal any times. To morrow to work be gin. It ‘s cleen eccepts for the talk. The in-habits live in draems. To raed this has need, not idees but a tenshn (to-trans-late of Twang): “After a land-like giourney a yuong man-Pan a rive deep in a rest hwere the her of his choise was live in a mall she has make. Green aster hang, man re-sieve no to-greet, re-turn to his ghest-there is no re-plies. Rael Zen he is to can make to get a-tention; the stud go to a nother art of rest and biuld his-self yeers. Later, new as-to-weep-like fall leeves, he ‘s line. He then drop. Every thing run throuh the rest to teech and say, Thank you.”

The Policeman’s Beard is Half-Constructed, Racter (1984)

The Policeman’s Beard is Half-Constructed is a collection of prose and poetry written by Racter (short for raconteur) a computer program created by William Chamberlain and Thomas Etter and published in 1984 to answer the question of what kind of language a machine, alien to human experience, would produce. The result, as the dialogue below reveals, is fascinating—and reminds me a little of Anne Carson’s poetry. (Thanks to Brian Rogers for this suggestion.)

BILL. I love a child.

MARCELLA. Children are fortunately captivating.

BILL. Yes, yet my love is excellent.

MARCELLA. My love is spooky yet we must have a child; a spooky child.

BILL. Do you follow me?

MARCELLA. Children come from love or desire. We must have love to possess children or a child.

BILL. Do we have love?

MARCELLA. We possess desire, angry desire. But this furious desire may murder a child. It may be killing babies someday.

BILL. Anyway let’s have a child.

MARCELLA. My expectation is children.

BILL. They will whisper of our love.

MARCELLA. And our perpetual, enrapturing, valuable fantasy.

BILL: I’ll record your journey through your immortal realms of terror and mild moony lustre, in soft sexual delusions of varied beauty. To delight the wanderer and repose his burning thirst and freezing hunger.

They let cords and stakes bind. The eternals began to erect the tent when Enitharmon felt a worm within her womb and with sharp pangs the hissings began; dolorous hissings and poisons round Enitharmon’s loins folding

The Country of the Ice Cream Star, Sandra Newman (2014)

Newman’s post-apocalyptic novel follows in the tradition of Riddley Walker, though set in the not-quite-so-distant-future. As we may expect in a world populated only be children and teenagers—all of the adults have been killed off by a plague—the language employed is a rich patois that one critic likened to “Jar Jar Binks narrating an audiobook of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road.”:

House begin to look a little itchy, before the firelight come. As the flickering raise, it show clear in the bust-out windows. Is like it be a life we woke inside. Then the roof go staining black and fire squeeze through the stain. Fire make a hole and flames push through the roof like angry hair.

The flame and sky two different kinds of bright. Sun look tame and sleepy while this fire go left and right so huge. It make us big and bright with nerves, although we Sengles, kin to burning. Keepers settle staring to the fire, her mouth agape. I settle to my fire trance.

Feature image: a still from one of the greatest movies of all time, Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome.

Stephen Sparks

Stephen Sparks is a reader, walker, and the owner of Point Reyes Books.