Speaking Truth to Power is as American as Apple Pie

America’s First Revolutionary Abolitionist Deserves a Statue in the Middle of Town

The debate about the suitability of Confederate generals as national heroes invites us to search the past for figures who better exemplify our declared ideals of democracy and equality.

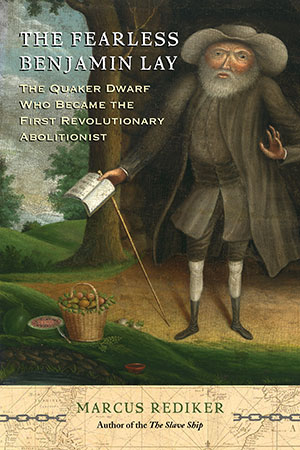

A little-known radical abolitionist from the 18th century, Benjamin Lay, deserves our consideration. Two generations before the emergence of an anti-slavery movement, Lay, a Quaker and a dwarf, endured persecution and ridicule as he fiercely attacked slavery and imagined a new, more humane way of life. Lay was born of humble origins in England in 1682, labored on the high seas, sailed to Barbados where he first witnessed the horrors of slavery, and then settled in Philadelphia—where he utilized dramatic guerilla theater in his fight against prominent Quaker (and other) slave owners. His long, lonely fight against bondage was nothing short of heroic. He deserves to be remembered and honored.

Lay staged public protests against wealthy Quakers to shock the Friends of Philadelphia into awareness of their own moral failings about slavery. Conscious of the hard, exploited labor that went into making seemingly benign commodities such as tobacco and sugar, Lay showed up at a Quaker yearly meeting with “three large tobacco pipes stuck in his bosom.” He sat between the galleries of men and women elders and ministers. As the meeting ended, he rose in indignant silence and “dashed one pipe among the men ministers, one among the women ministers, and the third among the congregation assembled.” With each smashing blow Lay protested slave labor, luxury, and the poor health caused by smoking the stinking sotweed. He sought to awaken his brothers and sisters to the politics of the smallest, seemingly most insignificant choices.

When winter rolled in, Lay used a deep recent snowfall to make a point to Quaker slave owners. He stood on a Sunday morning at a gateway to the Quaker meetinghouse, knowing all Friends would pass his way. He left “his right leg and foot entirely uncovered” and placed them in the snow. Like the ancient philosopher Diogenes, who also walked barefoot in snow, he again sought to shock his contemporaries into awareness.

One Quaker after another took notice and expressed concern, urging Lay not to expose himself to the freezing cold. He would surely get sick. Lay listened carefully to their words, then replied, “Ah, you pretend compassion for me but you do not feel for the poor slaves in your fields, who go all winter half clad.” He made two points: First, anyone without proper clothing in cold weather deserved compassion. Second, Quakers were not practicing a maxim central to their faith, drawn from Matthew 7:12, “Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them: for this is the law and the prophets.” So saith Lay the prophet.

On another occasion, Lay called one morning on an unnamed gentleman “of considerable note,” who politely invited him to sit down to breakfast with his family. As Lay began to take his place at the table he saw a man of African descent appear at the door of the dining room to serve the meal. Lay turned somberly to his acquaintance and asked, “Dost thou keep any Negro slaves in thy family?” When the gentleman answered yes, he did indeed keep slaves, Lay pushed back and stood up from the table. He announced, “Then I will not partake with thee, of the fruits of thy unrighteousness.” Lay would have no intercourse with those who owned slaves. He walked out.

Lay also began to disrupt Quaker meetings in and around Philadelphia. The 19th-century radical Quaker Isaac Hopper relayed the following story, which he had apparently heard as a child, to fellow abolitionist Lydia Maria Child:

At the Monthly meeting of Friends [Lay] was a diligent attendant.

At that time, many members of the society were slaveholders. Benjamin gave no peace to anyone of that description. As sure as any character attempted to speak to the business of the meeting, he would start to his feet and cry out, “There’s another negro-master!”

Never afraid to point the finger of shame, Lay insisted that slave holding and Quakerism were utterly incompatible. “No justice, no peace” was his message.

Lay carried his guerrilla theater across the city, visiting a variety of churches and ranting at ministers he disliked, just as he had done in London and Colchester. According to Roberts Vaux, he “attended all places of public worship, without regard to the religious professions of their congregations,” sometimes in sackcloth to emphasize his humility before God. He listened to the sermons and judged them, usually harshly. His responses “were sometimes so long and vehement as to require his removal from the house; an act to which he always submitted without opposition.” When an ungodly minister owned slaves, as was not uncommon in Philadelphia, Lay doubled his wrath.

These rants sometimes went awry. Ministers did not as a rule welcome a stranger’s harangue, least of all in the presence of their congregation. When a Philadelphia preacher announced during a sermon that he heard “a voice from Heaven,” Lay blurted out that “from thy life, and preaching, I question whether thou ever heardst a voice from heaven in thy life, and if thou didst, I am sure thou hast not obeyed it.” Outraged, the clergyman seized a bullwhip and chased his critic from the church. Yet, not all congregants took Lay’s interventions so seriously. On another occasion, Lay went to (Anglican) Christ Church in Philadelphia to hear the Reverend Robert Jenney preach about Judgment Day. As the congregation filed out of the church Lay stood at the door and asked person after person, “How can you, by such preaching as you have been hearing, distinguish the sheep from the goats?” A gentleman grabbed Lay’s bushy beard, gave it a hard tug, and said merrily, “By their beards, Benjamin, by their beards.”

These spectacular prophetic performances repeatedly dramatized what was wrong in both the Society of Friends and the world at large. For a quarter century, Lay railed against slavery in one Quaker meeting after another, in and around Philadelphia, confronting slave owners and slave traders with a savage, most un-Quaker-like fury. Whenever he performed guerrilla theater, his fellow Quakers removed him by physical force as a “trouble-maker” or “disorderly person.” He did not struggle against eviction, but back he came, again and again, undeterred, or rather more determined than ever.

He began to stage his theater of apocalyptic outrage in public venues, including city streets and markets. He refused to be cowed by the rich and powerful as he freely spoke his mind. He practiced what the ancient Greeks called parrhesia—free, fearless speech, which required courage in the face of danger. He insisted on the utter depravity and sinfulness of “Man-stealers,” who were, in his view, the literal spawn of Satan. He considered it his Godly duty to expose and drive them out. His confrontational methods made people talk: about him, his ideas, the nature of Quakerism and Christianity, and, most of all, slavery. His first biographer, Benjamin Rush—physician, reformer, abolitionist, and signer of the Declaration of Independence—noted that “there was a time when the name of this celebrated Christian Philosopher. . . was familiar to every man, woman, and to nearly every child, in Pennsylvania.” For or against, everyone told stories about Benjamin Lay.

The zealot carried his activism into print, publishing in 1738 one of the world’s first books to demand the abolition of slavery: All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates. All enslaved people were innocent, Lay believed, so he called for all to be emancipated, immediately and unconditionally, with no compensation to slave owners. Slave keepers had transgressed the core beliefs of Quakerism in particular and Christianity in general: they should be cast out of the church. Lay wrote his book at a time when slavery seemed to many people around the world as natural and unchangeable as the sun, the moon, and the stars in the heavens. No one had ever taken such a militant, uncompromising, universal stand against slavery in print or in action. Lay demanded freedom now.

Perhaps because he had little education, Lay ignored the rules of convention in writing his book. It made for odd reading, then and since, but it is a veritable treasure trove for a historian: a mixture of autobiography; prophetic Biblical polemic against slavery; a commonplace book into which he dropped writings by others as well as his own thoughts on a variety of subjects: haunting, surreal descriptions of slavery in Barbados; an annotated bibliography of what he read; and a vivid, scathing account of his own struggles against slave owners within the Quaker community. It is a founding text of Atlantic antislavery.

Lay knew that the wealthy Quakers who vetted all publications would never approve his book. Most of them owned slaves. So he went directly to his friend, the printer Benjamin Franklin, and asked him to publish it. When Franklin saw a confused jumble of pages in a box he expressed puzzlement about how to proceed. Lay answered, “Print any part thou pleaseth first”—assemble the materials in any order you like. As one exasperated reader later noted of the different parts of the book, “the head might serve for the tail, and the tail for the body, and the body for the head, either end for the middle, and the middle for either end; nay, if you could turn them inside out, like a glove, they would be no worse for the operation.” (Lay was one of the world’s first postmodernists.) Franklin agreed to publish the ringing rant against slavery, knowing full well that the weighty Quakers assailed in it would howl in protest. He quietly left the printer’s name off the title page.

*

Part of Lay’s guerrilla theater was his distinctive appearance. He was a dwarf or “little person,” standing a little over four feet tall. He was also called a “hunchback,” meaning that he suffered from over-curvature of the thoracic vertebrae, a medical condition called kyphosis. According to a fellow Quaker,

His head was large in proportion to his body; the features of his face were remarkable, and boldly delineated, and his countenance was grave and benignant. He was hunch-backed, with a projecting chest, below which his body became much contracted. His legs were so slender, as to appear almost unequal to the purpose of supporting him, diminutive as his frame was, in comparison with the ordinary size of the human stature. A habit he had contracted, of standing in a twisted position, with one hand resting upon his left hip, added to the effect produced by a large white beard, that for many years had not been shaved, contributed to make his figure perfectly unique.

Lay’s wife, Sarah, was also a “little person,” which caused the enslaved Africans of Barbados to remark in delighted wonder, “That little backarar [white] man go all over world see for [to look for] that backarar woman for himself.” Yet Sarah was more than a help-meet; she was a principled abolitionist in her own right. Lay was by some definition “disabled,” or handicapped, but I have found no evidence that he thought himself in any way diminished, nor that his body kept him from doing anything he wanted to do. He called himself “little Benjamin” but he also likened himself to “little David” who slew Goliath. He did not lack confidence in himself or his ideas.

Lay’s prophecy speaks to our time. He predicted that for Quakers and for America, slave keeping would be a long, destructive burden. It “will be as the poison of Dragons, and the cruel Venom of Asps, in the end, or I am mistaken.” As it happens, the poison and the venom have had long lives indeed. We still live with the consequences of slavery: prejudice, poverty, deep structural inequality, and premature death. Just as tellingly, Lay counseled his readers to beware rich men who “poison the World for Gain.” It may have taken more than two and half centuries, but it seems that the world is finally beginning to catch up with the prophet’s radical, far-reaching ideas through a growing, if far from universal, environmental consciousness.

It is time to make a prominent place for Benjamin Lay in American history. We live in a time when some of those once regarded as national heroes are being removed from their pedestals. Lay embodies a set of higher ideals and is a more suitable hero for a society that claims democracy and equality as its core historical values.

__________________________________

From The Fearless Benjamin Lay: The Quaker Dwarf Who Became the First Revolutionary Abolitionist, by Marcus Rediker. Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Marcus Rediker

Marcus Rediker is Distinguished Professor of Atlantic History at the University of Pittsburgh and Senior Research Fellow at the Collège d’études mondiales in Paris. His books have won numerous awards and been translated into fourteen languages. He lives in Pittsburgh.