Six Tales About Fathers and Sons That Do Not Feature Fathers and Sons

Adam Ehrlich Sachs on VAST, FATHOMLESS, and MULTIFARIOUS conceptual Fathers

If you decide to write a book about fathers and sons after Abraham and Isaac, and after Icarus and Daedalus, and after Odysseus and Telemachus, and after Oedipus and Laius, and after Hamlet and King Hamlet, and after Gregor and Mr. Samsa, and after Turgenev and Freud and Harold Bloom and Bellow and Roth and Edward St. Aubyn, you’ll likely find, as I did, that the Western tradition of father-son literature becomes at some point a second subject of your book, a second father, a father perhaps slightly less corporeal and a little more conceptual than your own father but who is every bit as imposing, inspiring, intimidating, insurmountable yet somehow easily surpassable, periodically embarrassing, lodged in your head in a way you don’t fully comprehend, surprisingly strong for its age, all of a sudden alarmingly weak, schmaltzy, stoical (just at the moment you’d like to see a little emotion!), central and irrelevant, one million times smarter than you and a million times stupider, infinitely complex and yet possible to encapsulate perfectly and pin down permanently with a single well-chosen adjective, albeit, of course, an adjective that forever eludes you. The Western tradition of father-son literature will not play catch with you, it will not build model rockets with you, it won’t take you bowling, and it will not pay for grad school, but it will, like your biological father, appear to stand in your book’s way while in fact being the very thing that makes it possible at all.

Later, when you’ve written the book, and you have to promote it, and you decide to write a reading list of books about fathers and sons, the Western tradition of father-son literature will suddenly loom up before you once again. “I AM VAST AND FATHOMLESS AND MULTIFARIOUS,” it will cry, just as your actual father has cried on so many (hurtful) occasions. “HOW CAN YOU POSSIBLY CHOOSE FROM AMONG ME?” And so, since your book, you tell yourself in your slightly affected way, was really about conceptual fathers more than any particular flesh-and-blood father, you introduce a constraint: here are six tales about fathers and sons that do not feature fathers and sons.

“A Message from the Emperor” by Franz Kafka

The father: The Emperor, on his deathbed, trying to deliver a message to you

The son: You, sitting at your window, dreaming up that message as evening falls

Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, The Judgment, and his Letter to His Father (which he sent, with characteristic Kafka logic, to his mother) may constitute, alongside Freud’s writing, the ur-text of modern father-son literature, but this tiny parable achieves in under a page maximal father-son poignancy and the utmost in father-son paradoxicality. The Emperor is on his deathbed, one of Kafka’s favorite places to put his patriarchs, for a deathbed is the perfect place to be nearly all-powerful while being nearly dead. (Recall the father in The Judgment, shivering in soiled undergarments under blankets in a room that’s almost pitch-black on a sunny day—yet “even if I’m at the end of my strength, it’s still enough for you, more than enough for you.”) The Emperor is likewise God-like and pathetically weak, capable only of whispering his final message to a kneeling messenger. And as for you—you are at once his “most contemptible subject” and the only person worthy of his last message. (Kafka has squeezed two filial-theological paradoxes into the first four lines, a superb rate of half a filial-theological paradox per line.) The messenger does his best to reach you with the Emperor’s message, to let some sort of communication transpire between you at the last possible moment, but he makes almost no headway, the obstacles standing between you and the dying old man are infinite, so all you can do is dream up the message for yourself, and, I imagine, write down this parable.

The Verificationist by Donald Antrim

The father: Richard Bernhardt, psychoanalyst

The son: Tom, psychoanalyst

On page 26 of The Verificationist, Richard Bernhardt of the Krakower Institute wraps Tom—his colleague, our narrator—in a multivalent bear hug that lasts for the rest of the novel. A few pages later this already very problematic hug, which Tom considers a kind of “metaphoric patriarchal rape,” becomes even more dire when the two colleagues start floating toward the ceiling of the Pancake House & Bar in which the Institute has gathered for its biannual meeting, an experience that Tom explains in his usual psychoanalytic terms: “I loved this awful man, and he was deeply in love with me. In order to bear this knowledge, and the attendant physical violation, our embrace, I had no recourse but escape into a transient psychotic breakdown…” Over the next hundred and fifty pages this Oedipal archetype hovering at the ceiling of the Pancake House performs various permutations of the father-son relationship: Tom begs Bernhardt not to drop him; Bernhardt promises Tom he won’t; Tom feels loved by Bernhardt; Tom feels crushed by Bernhardt; Tom feels Bernhardt’s erection against the small of his back; Bernhardt rocks Tom gently in his arms and finally, at the end, lets him go. It is impossible throughout to distinguish reality from the unremitting psychoanalytic blather, since the events of the novel are basically that blather concretized.

Weimar Culture: The Outsider as Insider by Peter Gay

The father: Monarchists, militarists, industrialists, Romantic irrationalists, and Nazis

The son: Liberals, socialists, Expressionists, the architects of the Bauhaus, and Jews

Peter Gay, who would later produce a magisterial if tendentious biography of Freud, attempting to rehabilitate him as a respectable scientific empiricist, here sees the rise and fall of Weimar Germany in blunt Freudian terms: the Revolution of 1918-19 that ended the Empire and ushered in the Weimar Republic was simply a “Revolt of the Son” (Jews, socialists, liberals, internationalists, avant-garde artists, etc.) against a tyrannical authoritarian father (imperialists, old conservative jurists, spiritual Rilke-reading youth in search of purity and wholeness and renewal, Heidegger, Hitler, etc.) And the downfall of the Weimar Republic—starting in 1925 with the election of the “sturdy paternal” Hindenburg and culminating later with the Nazis—is therefore, of course, the corresponding “Revenge of the Father.” (Kafka’s tales of anxious sons and autocratic fathers are, from this perspective, less a reflection of his infinitely subtle inner life than a sign of his times—Kafka tapping into the zeitgeist, the zeitgeist tapping into Kafka.) It is a neat little story of Oedipal conflict, tidy, dramatic, and symmetric, though Gay seems to equivocate on just how literally we’re supposed to take it.

“Babel in California” from The Possessed by Elif Batuman

The father: Isaac Babel

The son: Isaac Babel scholars

Like you at your window in “A Message from the Emperor,” the Babel scholars in Elif Batuman’s very sad and very funny farewell to academia long for a message from their patriarch, the autumnal bespectacled Babel, executed in the Lubyanka Prison in January 1940, and, like Kafka’s emperor, infinitely far away from them at their Palo Alto Babel conference. Batuman’s catalog of academic foibles and methods doubles as a catalog of all the ways we try and fail to know another person, particularly someone from the past, particularly someone who was probably not all that easy to know even in life. You visit the places he visited (“Lemberg was indeed a beautiful city,” concludes one such scholar), you bend his words to your own purposes (“There are not so many differences between Jews and Chinese,” explains a Chinese filmmaker preparing to shoot a Chinese Red Cavalry), you ponder the things he left behind (shaving cream, suspenders, sandals), and, above all, you interrogate those who knew him, in this case Babel’s difficult elderly daughters, who are supposed to be the stars of the conference before it becomes obvious that they’ll bring the scholars no closer to understanding their father. After a particularly inane and irrelevant story told by one of the daughters, Batuman feels “a strange feeling, close to panic. What if that was it, the thing that only she could tell us?”

“On The Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life” from Untimely Meditations by Friedrich Nietzsche

The father: History

The son: Life

In this early installment of Nietzsche’s lifelong crusade against filial piety, he argues that by treating our fathers and forefathers too gently—paying them too much respect and too much attention, remembering them too well—we destroy both them and us. (I also choose to read this essay as a helpful screed against historical verisimilitude in historical fiction. Whenever Nietzsche says that history should be employed only in the service of life, I mutter, much less impressively, “and only in the service of historical fiction.” In general I like to neuter Nietzsche’s grand fearsome pronouncements on life by applying them only to fiction, where they don’t matter at all. I turn all of Nietzsche’s pronouncements into tinny little craft tips, and dress up the philosopher of the death of God as an MFA instructor. This Nietzsche-neutering is actually in the spirit of his own essay.)

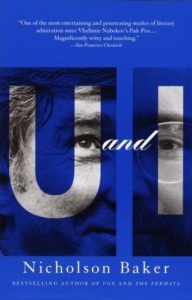

U and I by Nicholson Baker

The father: John Updike

The son: Nicholson Baker

Something similar to Nietzsche’s exaltation of ignorance and forgetting over knowledge and memory seems to animate Nicholson Baker’s decision not to reread any Updike—or to read any of the Updike he had not yet read—before embarking on this reckoning with his literary progenitor: rather than embalm the actual Updike with artificial erudition, he wants to portray the warped but living Bakerian Updike that occupies his, Baker’s, head, inspiring and intimidating him, spurring and silencing him, proscribing certain images (drizzle on a window screen) and words (“consort”) from Baker’s fiction because Updike got them down first. (The fathers in my book likewise have less to do with my father than with an intangible conceptual adaptation of my father whom I actually fathered myself, in my own head, and who now lives in my own head, and with whom I spend a great deal of time.) Baker’s entertaining analyses of various anxieties of influence include an entertaining analysis of his anxiety about the influence of Bloom’s Anxiety of Influence, which, he admits, he has also not read. (Incidentally, Baker’s confessions of what he has not read are infectious, and there’s nothing I like more now than confessing that I haven’t read something, with the exception perhaps of quietly admitting that I have read something.) Recently, J.C. Hallman transformed Baker’s account of literary anxiety into a source of literary anxiety, forcibly maturing Baker from literary son into literary father in his book B & Me (which I haven’t read), thus conjuring the hellish image of an infinite chain of anxious alphabetically-titled literary-paternal reckonings, each one inadvertently spawning the next, and so on until the end of the world.

Adam Ehrlich Sachs

Adam Ehrlich Sachs studied atmospheric science at Harvard, where he wrote for the Harvard Lampoon. His fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, n+1, and Harper's, among other places. He lives with his wife in Somerville, Massachusetts. His book Inherited Disorders is out now.