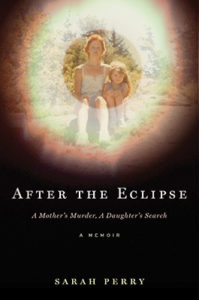

Searching for My Mother, 16 Years After Her Murder

Sarah Perry Travels Back to the Scenes of a Crime

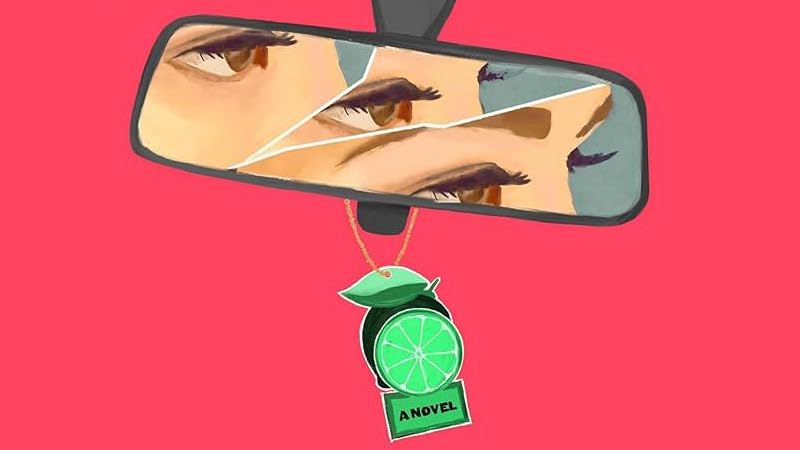

One cold March, just a few years ago, I rented a flawlessly clean silver car and drove up to Maine from my home in Brooklyn. I’d made it just north of Boston when the trees started to press in close, and as the network of pavement thinned down to I-95, I began hours of sitting in the dark, following that one road ever north. I held my left hand steady on the wheel at six o’clock, sifted through pop songs and ad spots with my right. I missed my early twenties, when I still had my own car and still smoked, moodily exhaling into the night on my semiannual trips up and down the East Coast, from college to home and back again. Once I entered Maine, I tuned in to WBLM, the classic rock station, one of the few clear signals that holds on through the mountains. ’BLM had been our station, the one Mom and I listened to on countless Sunday drives through tunnels of sunlit trees. I listened to David Bowie and Aerosmith and Fleetwood Mac and Heart, and Mom was alive again, then newly dead again, then long gone and faded away. I still knew all the words.

About an hour into Maine, I finally turned off the highway, winding farther north until I reached my Aunt Carol’s house. It was midnight, and I shivered as I got out of the car, unprepared for the crystalline cold that had been waiting for me. Carol and her husband had been asleep for hours, but through a front window I could see they had left the yellow light on over the stairway to my old bedroom. The car door made a sharp sound when I pushed it shut, the trees replying with a softened echo. I stood outside for a minute, head swiveled up to the crowded stars, until something rustled in the ditch along the road, and I remembered where I was, and the fear moved back into me, running along my veins, racing up and down my limbs, warming me and settling in.

The fear waits for me still, always worse when it is dark or cold. But it’s the half hour of transition from day to night that’s hardest, watching the light seep from the landscape, taking with it its illusion of safety. On the rare days when I’m here in winter, when dusk starts sliding over this valley at four o’clock or even earlier, I have to fight against panic. I turn away from the windows, stir my aunt’s soup, sit with my silent uncle watching race cars hypnotically circle an endless oval track. Once it is truly dark out, I feel a bit better: there may be hours of nervousness to get through, but now I’m in them. I’ve been here before, and no matter how bad things get, some part of me always remembers that I’ll come out the other side.

So it’s good that I drove as the darkness came down, listening to the old soundtrack. It all makes sense. It’s more important that this trip be true than easy.

*

I get up early the next morning and have coffee and cereal with Carol. She is cheerful and I am cheerful and we do not mention why I am visiting. I don’t visit often.

I get into the car and make my way to the Maine State Police barracks in the town of Gray. It’s a two-hour drive, and I retrace much of last night’s ground, this time in cheerful daylight. I stop at Dunkin’ Donuts and everything tastes like high school.

Twenty minutes later, I turn into the barracks parking lot, sand and salt crunching under my tires, and park in front of a long, low building covered in sky-blue clapboard. This is not the imposing cement-and-glass fortress I’d imagined. There’s a little portico above the entrance, held up by thin blue columns. The windows are small. It looks like a nursing home, or a motel in a deserted oceanside town. There are about ten spots in the parking lot, only two of them filled by cruisers.

A flagpole rises from a closely shorn strip of dull winter grass, and a police officer is raising the flag. He’s the only person in sight: dark gray buzz-cut hair, torso bulky with muscle beneath his neat blue uniform, pulling a flimsy chain, hand over hand. He turns toward me and I pause before getting out. It’s Walt, the detective I know best. I know it’s him, but at the same time I’m unsure; at this distance, cops all look the same. He gives me a broad smile as I step out of the car and walk closer.

Walt greets me with fatherly effusiveness, and I feel guilty for my hesitation. He’s a kind man who has seen the worst of human behavior, with a carefully restrained sense of humor and a broad accent; a north woods version of the classic gumshoe. He’s now commander of the Maine State Police field troop unit in southern Maine, but he spent many of his years in the division devoted to major crimes. A few detectives led Mom’s case over the years, but Walt was the one in charge the longest; he knows so much about my early life, more than anyone. More than my aunts and uncles. More, in fact, than me.

Walt ushers me to a conference room that’s been reserved for the next few days. Susie, a witness advocate from the attorney general’s office, is waiting; she greets me with a warm hug. I haven’t seen her or Walt since the trial four years ago, and this reunion gives me comfort: there is so much I don’t need to explain to them.

Susie is chatty as I settle in and scan the room. This is more like what I had expected: laminated wood conference table, big projector screen, American flag hanging limp in the corner. Susie asks about my apartment, my work, what it’s like in the city. I answer her questions while trying to remember what I know about her. I ask about her fiancé, her teenage niece.

Soon Walt excuses himself to go down the hall to his office, says he’ll be around all day if I need him. Susie and I turn to the boxes and binders on the conference table. There are about ten four-inch binders, each crammed with paper, plus three cardboard file boxes. Susie lifts the tops off them one by one—they, too, are full of paper.

“So . . . there’s a lot here,” she says. “I’m not sure what you’re lookin’ for, but you can have anything you want.”

We agree that I’ll sit down and sort through everything, and that as I identify things I’d like to take with me, I’ll hand them to her and she’ll make copies. I am embarrassed by her generosity; I had expected to do all the work myself, but she assures me she’s happy to help. She’s set aside three whole days. As I start sifting through handwritten police notes, transcripts of interviews, and forensic documents, it becomes clear that I want nearly everything. I don’t know yet what will be helpful; I need to get it all home with me so I can really look at it. Hold it close. Think. So many other people have seen this material, and now I want it for myself. The prosecution kept the story necessarily simple: here’s the man who killed her; this is how he did it. But a violent act is an epicenter; it shakes everyone within reach and creates other stories, cracks open the earth and reveals buried secrets. I want those stories, those secrets.

My mother’s killer had twelve years of freedom before he was identified. In all those years, the state police and the cops in my hometown kept searching, kept interviewing, adding to this huge file. When asked why he and his colleagues remained so actively involved in this particular case, Walt said there were two reasons. The most obvious was that they had a huge amount of evidence; the case was tantalizingly solvable. But there was a more personal reason, too. They were angered and saddened by the fallout: the only child of a single mother, left alone.

Susie warns me, right away, about photos. She thinks she pulled them all out, but the files are disorganized, having passed through so many hands over the years. I agree to give her any photos I find without looking at them, if possible. I saw them at the trial four years ago; I don’t need to see them again.

About an hour later, I pull a sheet of paper off a pile and beneath it is a photo, facedown, thick smooth paper with the brand name printed diagonally in ghostly blue. Susie’s down the hall, and because she’s not standing right here, my hand turns it over before I can stop. I watch this hand move of its own accord, and as the photo flips, I think, I can take it. It’ll be fine. But it’s the worst one, a horrifying picture of my mother’s body. A close-up. And I am instantly angry with myself. I am tired of this impulse to wound myself so that I can prove that I’ll heal. When Susie comes back, I say only, “I found a photo,” and hand it to her. She sighs, makes a clucking noise with her tongue, apologizes. I hold my face perfectly still. If I worry her, she might put a stop to this. And if there are more file boxes somewhere, I don’t want her holding them back.

__________________________________

From After the Eclipse. Used with permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Copyright © 2017 by Sarah Perry.