Retracing Willa Cather's Steps in the South of France

Marcia DeSanctis Looks for Traces of Cather in Le Lavandou

A few years ago, while researching my book on France, I immersed myself in the country’s rich travel writing canon, and decided to retrace the voyages (or parts of them) of many of my literary idols. In Nîmes, I imagined Colette dancing in the Jardins de la Fontaine; I conjured the ghost of a bored Henry James by the Rhône River in Arles; and in Chamonix, I pictured 16 year-old Mary Godwin unwittingly gathering inspiration for Frankenstein while hoofing it across the Alps with her future husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley. With her 1908 road trip classic A Motor Flight Through France always stuffed into my bag, Edith Wharton was my frequent guru and guide. But no one lit my path brighter than Willa Cather, who I have read and admired for as long as I can remember.

The collection of essays, Willa Cather in Europe: Her Own Story of the First Journey, is a series of dispatches she filed for the Nebraska State Journal in Lincoln to help pay for her voyage. It was 1902, and Cather was accompanied by her friend Isabelle McClung. The book contains, to my mind, some of the most evocative travel writing in the English language. The stories bear all the elements—personal reflection, descriptive detail, observational insight, and cultural depth—we strive for when writing about place, and in perfect proportion.

At the time of her trip, Cather was teaching English and Latin at a Pittsburgh high school, while editing and writing for several local publications. She was not yet 30 when she went to Europe, but she was electrically trying her hand at everything: poetry, short stories, drama criticism, and taking in every cultural input she could. “She was drinking from a firehose,” says Cather scholar Robert Thacker of St. Lawrence University, due, not in small part, to her remarkable focus and drive.

She was not blue-blooded Edith Wharton, who had grown up in the first-class section of European trains, with servants unpacking her trunks. Willa Cather was of the American prairie, where her father ran a farm loan business, and she developed her love and deep scholarly knowledge of French literature at University of Nebraska, where she also studied Classics. When she finally went to France, she visited the graves of writers she long admired and in the case of Chateau d’If—the island fortress near Marseille where the Count of Monte Cristo was held prisoner—the settings of great literary dramas.

In 1902, she was on the cusp of her brilliant career. It is with this in mind—the writer on the verge of greatness, taking the voyage of a lifetime that would also inspire much of her fiction—that I went to Le Lavandou, a village in the Var department of the south of France, where Cather penned the most beautiful dispatch of all. The nine page-essay is so powerful that it moved me to follow her tracks: to breathe the same piney air, look out at the same blue Mediterranean bay, and attempt to channel, or at least understand, the tranquility and bliss she described that week in September. “Out of every wandering in which people and places come and go in long successions, there is always one place remembered above the rest because the external or internal conditions were such that they most nearly produced happiness,” she writes. “I am sure that for me that one place will always be Lavandou.”

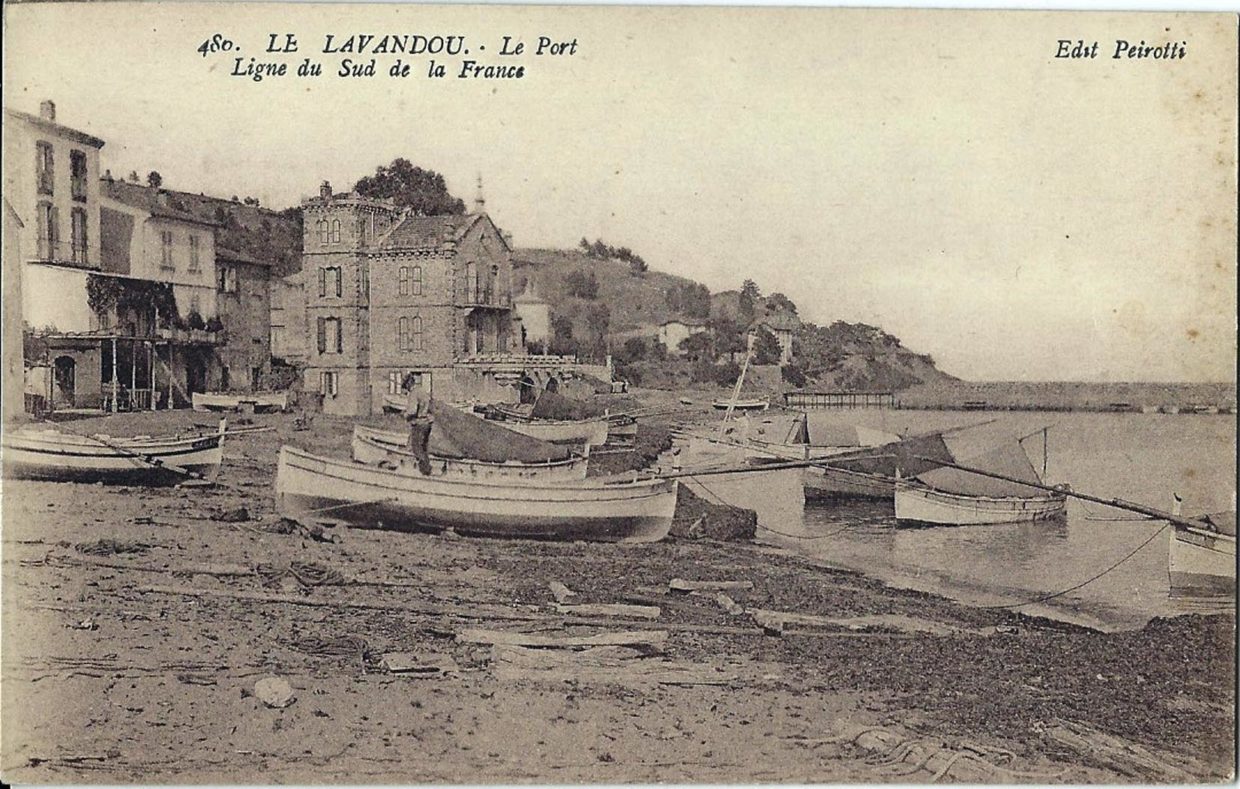

Via Service Culturel du Lavandou

Via Service Culturel du Lavandou

Cather had begun in London, gone through Paris and the papal city of Avignon, and found herself in this small fishing village just east of Toulon and south of what we now call Saint Tropez. She arrived by the tiny train—the one whose arrival she would anticipate daily for its delivery of ice. Like Father Latour in Death Comes for the Archbishop and Thea Kronberg in Song of the Lark, all her senses were firing as she took in her revelatory new surroundings in a remote place that, though long inhabited, was barely on the map. She ate peaches, langoustes and excellent fish. The air was scented with dried lavender; the landscape was of pine, green fir and sea “reaching like a wide blue road into the sky.” Cather described a primitive place, a “principality of pines,” where the soil was too sandy to grow anything but olives, grapes and figs, and the people so poor, she was uncertain how they survived.

Naturally, much has changed in the intervening century, as I saw when I arrived one September morning. There is still a station there, where the bus from Hyères dropped me off, but the train that once carried Cather is long gone. There are few humble fishermen, and the barefoot sailors are now coming off their 40-foot catamarans into a massive and quite posh marina. Some of the stores sell essentials for the sailboat crowd, like rain slickers and rope. In Cather’s time, there was one café. Now there are dozens, and all are packed until late at night. The square remains lined with sycamore trees, above which a Ferris wheel now spins dreamily. But the sky is still eternally blue, the air is fragrant with summer, and the village sits in soft, shadowless sunshine.

Photos by Marcia DeSanctis

Photos by Marcia DeSanctis

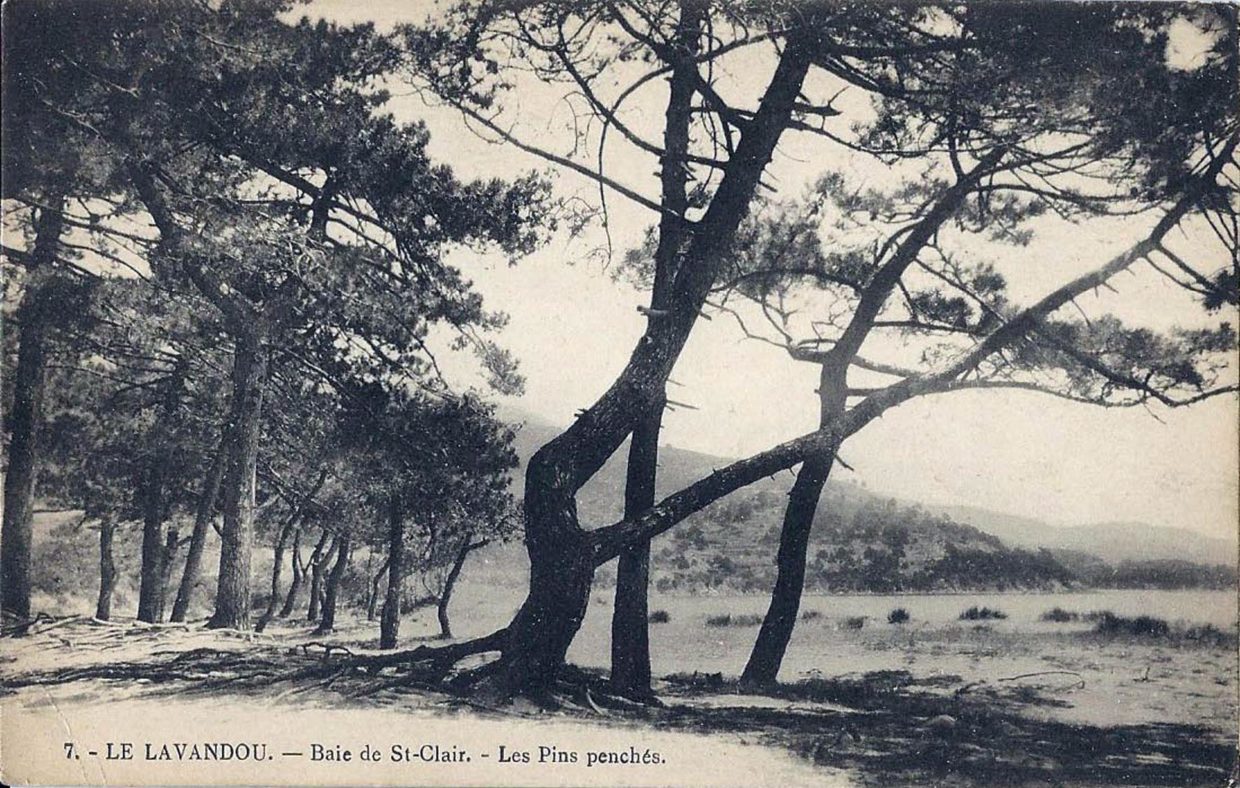

Cather and McClung stayed at the bare-bones winter home of a painter who was away in Paris. Some scholars believe it was Henri-Edmond Cross, who lived at Saint-Clair, just up the shore from Lavandou, but Raphaël Dupouy, the town’s cultural attaché, believes it was probably a somewhat lesser known figure. Many artists lived and worked in this remote idyll, most notably Theo van Rysseberghe. Both he and Cross famously painted the vistas at Saint-Clair. The town has created the Painter’s Trail along and behind the coastal promenade, so the visitor can experience the vivid light and color that drew the neo-impressionists to this impoverished backwater. Cross’s home no longer exists, at least in any discernable way, but even if it was not where she and McClung stayed, it was still difficult for me to place their location precisely, especially since the dusty paths that led to the cottages above the beach are certainly long gone.

The pair spent hours on the porch of the shabby villa; Cather wrote that it was “good for one’s soul,” to “do nothing but stare at this great water that seems to trail its delft-blue mantle across the world.” I imagined the writer so removed now from the high culture she had immersed herself in throughout Europe, where she connected so closely with the great minds that helped form her. What a balm in must have been to turn down the pressure and lower expectations for a spell. Bathed in the breeze, with pine needles dropping on her reposing body, she writes of almost perfect peace, much as her Song of the Lark protagonist Thea Kronberg would do when she was sheltered by Panther Canyon.

VIA Service Culturel du Lavandou

VIA Service Culturel du Lavandou

Cather also describes a plateau on the flat top of a cliff extending out to the sea, on which stood a lone pine on the tip of a promontory. I walked the long, narrow trail cut into the rocks from Lavandou to Saint-Clair, six times in all, hoping to see what mesmerized her for days. I never found the promontory, but when the light faded my first afternoon, I pretended I did. Sure, I thought, looking at the craggy formations that sliced into the bay. Waves slung over the outcrops and I watched them for hours without distraction.

She and McClung ate dinners at the Hotel Méditeranée, a grand old place that is no more, where back then a lonely Parisian was the only guest. There is now another structure of the same name, a lovely modern hotel, where I might stay if I return one day. There are shiny villas, low-slung apartment buildings, and buzzing cafés built into what was, in Cather’s time, dense vegetation. But the pines still grow mightily over this once-barren landscape, fill the air with their scent and provide cool refuge. The trees are massive and bent from the constant wind, and it is soothing to look up into the canopy and imagine that my eyes see what Willa Cather saw. The view skyward is not much different from any other shaded spot along the Côte d’Azur, but here, I was transported all the same. I had not managed exactly to retrace her steps, but the mission had put some pieces together for me. Words connect us all—the dead, the living, the great, the ungreat, but so can that which never changes: the rare stillness under a pine tree, the sound of the sea.

Photos by Marcia DeSanctis

Photos by Marcia DeSanctis

“No books have ever been written about Lavandou, no music or pictures ever came from here, but I know well enough that I shall yearn for it long after I have forgotten London and Paris,” she writes. “One cannot divine nor forecast the conditions that will make happiness; one only stumbles upon them by chance, in a lucky hour, at the world’s end somewhere, and holds fast to the days, as if to fortune and fame.”

In Le Lavandou, Cather ate, walked, pondered and gathered. She drank brackish wine, bought figs, chatted with passing fishermen, collected blossoms. She observed. She rested, before moving on for the “glare and blaze of Nice and Monte Carlo.” She was firing sparks and making mental connections. She found a little place with much she valued and that gave her tranquility. She took a breath and leaned up against it, as if preparing for something. “She knew she was going to be Willa Cather, and the people around her knew it too,” says Robert Thacker. Her first book, April Twilights, a collection of poems, would be published the following year.

Marcia DeSanctis

Marcia DeSanctis is a former television news producer who has worked for Barbara Walters, ABC, CBS, and NBC News. She contributes to Vogue and Town & Country magazines about health, wellness, and beauty. Her essays, articles, and stories have appeared in numerous publications including The New York Times, Marie Claire, Tin House, Creative Nonfiction, The Coachella Review, The Christian Science Monitor, Roads and Kingdoms, The Sunday Telegraph, Architectural Digest, O the Oprah Magazine, National Geographic Traveler, More, BBC Travel, Yahoo Travel, Entropy, Off Assignment, and many others. Her travel essays have been widely anthologized, including five consecutive years in The Best Women's Travel Writing and four in The Best Travel Writing. She is the recipient of five Lowell Thomas Awards for excellence in travel journalism, including Travel Journalist of the Year for her essays from Rwanda, Morocco, Russia, Haiti, and France, and a Solas Award for Best Travel Writing. She holds a degree from Princeton University in Slavic Languages and Literature as well as a Masters in International Relations from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. She lived and worked for several years in Paris and travels as much as possible to France.