On Taiwan and Refusing to Stay Silent

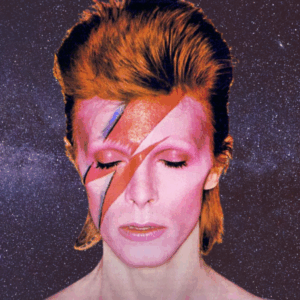

"If I cut my tongue free, I may find I like the taste of blood"

The artist comes next She waits for

the listeners too What if they’re all dead or

deafened by grief or in prison Then

there’s no way out of it She will listen

It’s her work She will be the listener

in the story of the stories

–Grace Paley, “A Poem about Storytelling”

“A dumbness—a shame—still cracks my voice in two, even when I want to say ‘hello’ casually, or ask an easy question in front of the check-out counter, or ask directions of a bus driver.”

–Maxine Hong Kingston, Woman Warrior

*

I recall to you the words of Apollonius of Tyana, speaking of fable-master Aesop: “But he by announcing a story which everyone knows not to be true, told the truth by the very fact that he did not claim to be relating real events.”

*

Once upon a time, an island formed. Thousands of years passed in which grass grew, died, grew; water flowed, froze, melted; animals were born, mated, birthed, died.

However, some argue, the place did not really exist until people arrived, scattered across its plains, settled in mountains, and called the island by a dozen-and-a-half names.

Some argue the island did not exist until it was made useful in the 1500s when the Chinese, in junks, crossed the strait and built an outpost away from the iron fist of the Emperor and called the place Taiwan and sometimes Greater Loochoo.

Others argue the island did not exist until the name was recorded in the salty, damp logs of Portuguese ships by men who glimpsed it through spyglasses and, dazed by the garlands of soft fog around the lush jade peaks, murmured Ihla Formosa, Beautiful Island.

Then came the Spanish, and then the Dutch, hoping to expand the Dutch East Indies north. Between the Europeans and the Chinese, there were two islands, Formosa and Taiwan, setting a precedent—the island would never be a place of single, fixed appellation.

*

After Trump’s call with the president of Taiwan last month, I feel a frustration that keeps me up at night tweeting (and then deleting) sarcastic and outraged comments about the mainstream media accounts that persist in misrepresenting Taiwan’s history. Though I am glad for some attention on Taiwan, I worry that Trump had stumbled onto territory that would put the country in danger. I worry that Taiwan, where half my family lives, would be treated as nothing more than a pawn in America’s dance with China. And I am exasperated by the language the western media uses to talk about Taiwan—language so clearly vested in China’s version of Taiwan’s history.

I had just returned home from Taiwan the week before. My first visit in a year-and-a-half, and I am in love with Taiwan all over again. Clean and efficient subways. Fresh hot soy milk every morning. Convenience stores where every conceivable need could be fulfilled. The chaos of 2.7 million people packed into the 104 square miles of Taipei. This country where my mother was born, and then raised in a ramshackle house with moldering walls and a leaking roof. I am supposed to be teaching my last classes of the semester—on Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese for my American Lit class—but I can barely concentrate on Yang’s graphic novel. Instead, I am thinking of Audre Lorde, whom I taught earlier the semester. I am thinking of her statement that anger can be used for growth, and I am thinking of how long I have feared my anger.

I have been trained well. I have stifled my anger with the desire to be a good filial daughter: say nothing, be obedient, smile and bite my leashed tongue. When I am talked over or down to, I just sigh and relent, unable to muster the will to fight my way into a conversation. On a panel, a male colleague verbally manspreads until there’s just space enough for me to make a two-sentence comment. It is rude to interrupt. I smile, and even invite him to grab a drink later, although I’m seething. I direct my anger at myself. On book tour, I share space with a man who is to be the host, but who goes on for long stretches about his own book, standing up and shaking it at the crowd, then leaving our table to wander the room when it’s my turn to speak. And still I smile. I write a kind inscription in his book.

I am polite and inoffensive.

I fear that I have turned myself into a stereotype.

*

In Woman Warrior, Maxine Hong Kingston’s narrator’s frenum is cut by her mother in attempt to free her to speak: “I cut it so that you would not be tongue-tied. Your tongue would be able to move in any language. You’ll be able to speak languages that are completely different from one another. You’ll be able to pronounce anything. Your frenum looked too tight to do those things, so I cut it.”

My mother never cut my tongue.

*

When Trump calls Taiwan and I watch a flood of misinformation about the country wash over the newspapers, I’m angry for the woman I met in Taipei who told me how her whole career had been driven by the search for the truth behind her grandfather’s death years ago, and how the documents the government finally released to her had his killers’ names redacted to “protect their privacy.” I’m angry for the retired professor who silently hands me a slim volume he has written about the murder of his father during Taiwan’s White Terror. For the daughter who receives an unsent letter from her imprisoned father 60 years after his execution. For the high school student who asks how he and his generation can know the hidden history of their country if it isn’t taught to them.

For the erasures of life and history by all-knowing white men who claim to be authorities on an island they haven’t even bothered to find out the history of.

*

In fiction, I can cut my frenum and free my tongue. My characters can be angry, critical, impolite in the ways I can’t bring myself to be.

*

I look through old drafts of my novel, versions of the book that I discarded. I’m surprised at how unencumbered they are. In one version, I narrate Taiwan’s history through the goddess Mazu who inhabits various characters—including a fly that feasts on the corpse of Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Chinese Nationalists, ally of the United States, and dictator of Taiwan:

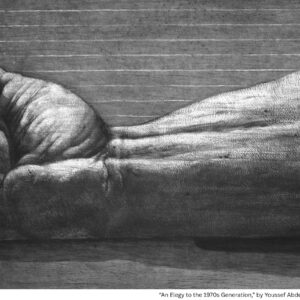

My friends, in the end, it is the Generalissimo’s heart that kills him, near midnight on April Fifth, 1975. He is 87 years old.

His kidneys fail and then his heart. The catheter bag flat as his urine dribbles to nothing and the fluid accumulates inside him, his body and organs swollen with dropsy, skin waxy. His heart seizes and stops. Everything loosens and the sheets, already damp with his death sweat, are now stained. His mouth falls open.

Before the screaming machines can alert the nurses and doctors (and even then, what point is there in revival? Nothing left to do but read the charts and note the time), I make my move. I go to his still-warm tongue and probe the soft, moist tissue. A fly’s dream.

Don’t worry—I will relieve you of the details. What is delectable to me is to you terror: the frozen face of your most terrible nightmare: your inevitable future.

The fly describes the taste of a dictator: the mix of power, desire, and “the bitter finish, the lingering vinegar. Perhaps this is the girding of all power—sweeping through me, knowledge that every decision has been tainted by fear.”

*

I am fascinated by Taiwan’s invisibility, about the willful silence from nearly every government (save 21) in the world, averting their eyes, pursing their lips like some patrician lady who has detected a foul smell and is too polite to comment.

Does Taiwan exist? Is it a country? What makes a country? As if 23 million people with their own land, history, passport, and constitution can be erased by saying so—or by silence.

As if enough people consenting to a fiction can make it truth.

*

In the 17th century, as the Manchu Tartars took over China, one of the palaces they besieged housed a Japanese woman who killed herself rather than surrendering. Her grieving son vowed revenge. He, like the island to which he eventually retreated, hoping to regroup his forces to retake China from the Tartars, went by many names: Cheng Gong, Tei-seiko, Koxinga.

The pirate-warrior Koxinga, with 25,000 soldiers, claimed Taiwan as his kingdom and demanded that the Red Hairs, as they called the Dutch, leave. Fort Provintia surrendered while Fort Zeelandia resisted, and Koxinga began his blockade, intending on drawing thirsty, starving Dutch from the fort. Meanwhile, those unlucky enough to be caught outside the fort, in the villages they had inhabited for years and years, were beheaded or crucified—nailed through wrist, ankle, and torso on crosses in the pirate-warrior’s response to these Christian colonialists. The Dutch eventually yielded, the Dutch East India Company left, and Koxinga and his heirs reigned for 20 years.

For almost 200 years, the island was Taiwan to one half of the world and Formosa to the other. Foreigners knew it on one hand as a barbaric island with treacherous shores where ships were wrecked and survivors beheaded or enslaved and, on the other hand, as a critical link in a trading network—the Americans nursed colonial hopes until the Civil War drew their attentions away, and the British and French made liberal use of Formosa’s treaty ports. As it was between the Qing Dynasty and Japan in 1895 in the Treaty of Shimonoseki, it was a game chip to be traded at the whim of others.

People should have become suspicious as early as 1904 when the Japanese colonizers began dismantling the Taipei city wall, turning 30,000 Mt. Beishihu stones into prisons and drainage ditches. This was no ordinary city wall—this was the last city wall built in the last planned city construction of the last Chinese dynasty. The un-building of the city was, by all appearances, practical, but I don’t need to explain to you the symbolism of the act.

*

“I did not speak and felt bad each time that I did not speak,” Kingston’s narrator says.

At what point does silence shift to a burden, cracking the shoulders and bending the back? I am bearing that weight, I realize, in my polite, closed-mouth smile. I seek the knife to unleash my tongue.

*

Because Taiwan was Japan’s “Crown Jewel” colony in their 1912 Colonial Exposition, what happened in 1937 surely was not a surprise. The Sino-Japanese War had broken out and the Empire made a frantic attempt to finally assimilate the subjects they had kept at bay for over 40 years. They initiated the “Japanization” movement, quite cunningly placing the burden of becoming Japanese on the colony itself—insinuating that it was a matter of desire. Japan stood at the finish line, urging their pets toward them with strings of sausages and the promise that these panting dogs could themselves become men if they trod the correct path. Being was not being, but performance. Walk on two legs and eat at the table and we will call you “brother.”

To further encourage assimilation, the Japanese outlawed the burning of paper money offerings to ancestors and deities, and new rules regulated home altars under the guise of “thrift.” Temples were demolished and statues of gods and goddesses were incinerated. Without offerings, immortals and ancestors starved. Heaven was thick with hungry ghosts.

Not only goddesses were excised—tongues too. Reward heaped upon reward—the family that assumed Japanese names and spoke Japanese would receive a plaque on the door: National Language Family. And the helpmeet to reward—punishment—was on hand with rolled shirtsleeves and paddle for those who spoke Taiwanese in public.

If there was one moment when the island felt the most entwined in the fate of the Japanese Empire, one morning when terror alerted them to the fact that, yes, they were indeed now part of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, it had to be May 31, 1945.

Fires—seething, spitting, roaring—burned in random pockets as far as one could see. Dogs sat down in the middle of the streets and howled. Rickshaw men raced to and fro carrying the injured while ambulances stuttered down streets, only to be blocked by piles of rubble. People ran into the streets, some wearing nothing but a sheath of charred skin.

The city burned for three days.

The Americans had dropped 3,800 bombs, for which some might have been grateful, because it is when the Americans come bearing only a single bomb that one should be very scared, as they did a little over two months later in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, turning sand into glass and people to ash.

*

After the Japanese left their colony in the defeat of World War II, the island was, for a brief, uncertain moment, again Formosa, and then the Kuomintang, losing the Chinese Civil War and reasoning that the Communists had no navy, fled to the island and it became the new home of the Republic of China.

Yet it wasn’t enough for the West, locked into its own Cold War, to distinguish between the ROC (Republic of China) and the PRC (People’s Republic of China)—China had been one monolithic place for 5,000 continuous years, as the story went, so how could it suddenly be two?—and ROC and PRC were clarified into Free China and Red China and any red-blooded American knew immediately which China to love, even though the closest thing to a panda that Taiwan could boast was a moon bear.

*

Humans are fickle. As the 20th century went on, the West came to love Red China as much as Red China loved the red bottles of cola sent by their new admirers, renminbi twinkling in their eyes, and Red China received the privilege of being just China. Since there could be only one China, the little sweet-potato-shaped island was left an orphan, nose pressed to the bakery shop window.

Though an orphan may remake and rename herself, the truth of her birth usually lies on a yellowing slip of paper in some drawer that sticks at the corners. It is always at the denouement that the maid runs into the room waving this piece of paper. So too with this island, a volcanic little Cinderella country which could come to the few world events to which it was invited bearing only a name decided by others: Chinese Taipei.

I don’t have to tell you how the name—not even a country but an adjective describing a city!—burned upon the breast, borne with a clenched smile while the stomach roiled.

*

I’ve written a novel about Taiwan nearly 400 pages and 14 years in the making. After Trump’s call, in an opinion piece for a major newspaper, I make the simple and completely reasonable argument that Taiwan is a country with its own history, that it’s more than just some invention created to keep things interesting between America and China. The piece is reposted here and there. In comments across the internet, I am called ignorant, a privileged American, white-washed. I am even called a whore.

I wonder when it became no longer the morally correct stance to defend a country’s right to self-determination against a larger authoritarian power.

*

If I cut my tongue free, I may find I like the taste of blood. I may find that I can negotiate around the words that have eluded me.

I may find that I can turn my anger into strength and state, loudly and firmly: Listen. We are here too. Listen.

Shawna Yang Ryan

Shawna Yang Ryan teaches in the Creative Writing Program at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa. She is the author of Water Ghosts and Green Island, a novel set in martial law era Taiwan. In 2015, she was the recipient of the Elliot Cades Emerging Writer Award from the Hawai'i Literary Arts Council.