On Falling Out of Love with Punk (and in Love with Books)

Mariah Stovall Definitely Prefers Alice Munro's Earlier Albums

“Lyrical” is the word I hear most often when I offer up my writing for critique. I’m not a songwriter or a poet but for seven years, music was the only thing that mattered to me. So it’s no surprise that my first attempt at creative writing ended up with its own soundtrack—a novel with each chapter named for a song, with its respective lyrics written in the margins. That wasn’t the plan but I couldn’t think of a better way to get those songs out of my head.

I cannot write without music, even when pressing my fingerprints onto plastic keys is the only sound in the room. I cannot quote any books or poems, but there is a library in my head. It’s slowly, sadly fading, not nearly as robust or insistent as it was when I was younger, but there are still so many songs suspended in my memory. I can conjure them or they can come out at will. Those lyrics slip and tangle on the page in sly references and stolen phrases, bubbling like inside jokes or the tender embrace of a childhood friend—long lost and irreplaceable. (Can you tell which part of that sentence I lifted from the name of a song?)

Peppering my writing with quiet shout-outs is an inversion of the uncanny feeling of stumbling across things in books that I once thought were the work of beloved bands. Seeing Bukowski’s Hot Water Music on a shelf drums up more for me than most of his readers, because I also adore the band who took their name from the short story collection. In high school, I underlined the “A boot stomping a human face forever” in my public library’s copy of 1984. I wrote Bad Religion’s name next to it, thrilled to find a familiar song title in the classic text. I hope someone read what I wrote and gave them a listen.

I once bought a Nelson Algren book after Dillinger Four dropped his name in a song. I began a ninth grade essay on Romeo and Juliet with an epigraph by The Lawrence Arms. Assigned The Tempest the next year, I chose my stalwart Bad Religion. It was the Crass album, not The Bible, that taught me the meaning of the feeding of the 5,000.

In college, I was self-righteous after serendipitously rereading Lolita on the heels of the new album by The Menzingers, my then-favorite band. The less-obvious Nabokov references on On the Impossible Past (like its title) playfully slapped me in the face. The next time I saw them in concert, in the back room of a Middle Eastern restaurant on the edge of LA, I screamed along to their versions of his words and tried not to drown in the crowd. I smiled. I was one of the lucky ones, in on the secret.

Like punk rock, literature is a kind of subculture. Most people can’t be bothered to dive in. Hopefuls can be dissuaded when a longtime member’s protective passion reads as exclusivity. But ask anyone who’s fallen hard for one and they’ll tell you—becoming part of an art scene will change your life (that’s not to say it won’t ruin it later). The communities spawned in these spaces are self-sustaining and addictive, inviting and demanding of intertextual references, nods to peers, and acknowledgements of their own history. All so you can fall in love again and again. If you love Martin Amis, then you have to read Zadie Smith. If you love Built to Spill, then you have to hear Forth Wanderers. Knowing every journal that originally published Alice Munro’s short stories is akin to being able to rattle off every band Mikey Erg plays in. Bonus points if you can name which record labels house those bands.

I fell for punk in an instant, hard and hungry like only a 13-year-old could. But I didn’t like to write, at least not at first. Starting stings until I find my rhythm. The only way I know how to approach deadlines and make word counts is by listening to the same album for hours on end. The revolution of a record stuck on an endless loop is in the way it blurs and emphasizes the passage of time. It pushes it forward and lets it stand still, always moving, if only in a circle.

In 2016, I read 110 books, including a handful of unpublished manuscripts (my own, a friend’s, and submissions to the publishing house where I work). Completing my English degree two years ago meant liberation from required reading. I envisioned a return to my childhood, spent behind stacks of books growing taller than me; we pushed up against the public library’s per-person limit while my mother (a writer, a reader) and older brother (a writer only) took out texts in my name.

But at 21, I could not, in good faith, return to my adolescent ways of reactive, short-sighted identity-making through the cultural products I favored. I had been a deliberately antiquated teenager, hell-bent on acquiring a classically discerning taste. Great, “serious” literature was the standard I imposed on myself. I was a black girl who thought myself revolutionary for reading canonically. I worshipped the agreed-upon greats. I wanted more men, more white men. I endeavored to consume them before they could consume me. Now David Mitchell and Jonathan Franzen can wait. Kaitlyn Greenidge and Han Kang are at the top of my list.

Growing up also meant losing my sixth sense, discovering that my capacity for and interest in merely feeling were not in fact bottomless. I grew exhausted from all the loving I’d done. In 2016, I went to one show. At every turn, I have been hyper aware of the decline in my concert attendance, in my failure to listen to every new album, form an opinion of every new band, dig my heels further into the space I carved out for myself on the front lines.

I barely believe it when I tell myself I am myself, with or without my music. Imagine biting down to find that you no longer love pizza. The loss of a purely instinctual sensory pleasure, once transcendent in the grace of its reliable simplicity. Cheese, sauce, bread. Three chords and the truth. Imagine disillusionment in the crust. Even worse is admitting that it isn’t the end of the world.

It isn’t just that I aged. Something else must have happened. I won’t blame my boyfriend, but in the face of his reciprocal version, I started weaning myself off the unrequited love I was addicted to. What was I thinking? My one-sided admiration of the songs themselves, if not the men making them, had been so safe. It was unreturnable, rejection impossible, and I wallowed in the glamour of all that tragedy. I had no interest in being loved back, in music having agency beyond that which I assigned to it. All music is like that, no matter how many face-to-face interactions musicians share with fans. We take the music and lyrics we are given and make them into the soundtracks of our own lives. We appropriate music like no other art.

I fell out of love with punk, slowly and steadily, eyes closed, head shaking in denial then basking in relief, like only an adult could. The routine erred towards boring, overshadowing the comfort it afforded me. I knew everything about it, but no matter how much I loved every little thing, I feared there would never be anything new. We were together for seven years. I still know its number; sometimes I call just to hear its voice. I hope at the end of all this we can still be friends. No other genre will ever tempt me the way it did, and for that, I am grateful. There is only so much room in my heart.

I didn’t have to choose between reading and listening to music, but I did. I read during my commute and my lunch hour, 120 minutes a day. That’s enough time for three or four albums.

I write rarely, at home with headphones on. I’m self-conscious in the quiet, where I can hear rejection looming and the throbbing footsteps of writer’s block approach. Like fear, my own writing is an instinct I’m reluctant to honor. But with music on, I can manage a delicate dance of listening to myself and someone else at the same time—even if the song is instrumental. With someone else making noise I can hide what I have to say until it’s perfectly polished and I’m ready to speak up.

Being a music fan (geek) clued me into another way of thinking. In the time I spent studying literature, songs kept bumping up against the pages. The discord reminded me how many ways there are to tell a story. Sometimes it even turned to harmony. I will always be jealous of musicians, wondering why I got stuck writing—just words, not music—instead. Why I’ve been condemned to reading while they get to play. But I’m learning to make the best of it. I think I found my own way to sing.

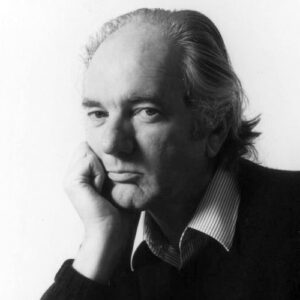

Mariah Stovall

Mariah Stovall has written fiction for the anthology Black Punk Now, and for Ninth Letter, Vol 1. Brooklyn, Hobart, the Minola Review, and Joyland; and nonfiction for The Los Angeles Review of Books, Full Stop, Hanif Abdurraqib’s 68to05, The Paris Review, Poets & Writers, and LitHub. I Love You So Much It’s Killing Us Both is her first novel and 24 Hour Revenge Therapy is her favorite Jawbreaker album. She lives in New Jersey.