All right then, a mother concedes, and grants her third and youngest son—he is five or six years old—permission to stay up to see the New Year in and to go out into the street with the grown-ups shortly after midnight to set off the New Year’s fireworks. These are the words that the child’s been working towards for months.

This child is me.

Apart from a few evenings with my grandfather—a very quiet man with huge hands that always smelled a little of bread and cigarettes—and my first day of school, which have stayed with similar clarity in my memory, I remember very little else from this time. It must have been New Year’s Eve 1970. My brothers had already been allowed to take part in the New Year’s festivities in years gone by and their stories had awakened great expectations in me, which would obviously be surpassed. I was told to take a nap. From nine to half past eleven I lay wide awake in my bed and heard the loud goings-on in the living room. My parents had invited some friends and relatives over to the new redbrick, three-story house situated at the end of a row of houses. Twenty or thirty meters behind the turning bay at the end of the cul-de-sac, behind what appeared to be abandoned garden plots edged by an unkempt hedge, the Bergisch Gladbach connection to inner-city Cologne swept by every twenty minutes.

When my mother came to wake me, I was already standing in the middle of the room putting on my trousers in the dark. She turned on the light, got me the checked shirt I’d been wearing during the day, went to the wardrobe, smiling, and pulled out the thickest sweater she could find. I stretched my arms up into the air, she pulled the sweater over my head, then stroked the hair from my forehead.

I ran downstairs to the living room. My brothers were already collecting the empty wine bottles set down all around the room, carrying them outside and positioning them in a row at the edge of the pavement. I followed after them. Stefan ran back into the house and soon reappeared with a bag of New Year’s rockets that my father had bought a few days before, maybe even before Christmas, at a shop called Kaiser Kaffee. My brother let me take a look in the red-and-white bag, pointed to each individual rocket and told me its special properties.

* * * *

It’s remarkable how clearly I remember this night; it’s my first childhood memory that fuses into a story, into a whole. All earlier memories survive only as individual images, individual words or smells, perhaps a look or a touch.

All at once the images begin to move.

I remember nothing of the actual, exact coming in of the New Year, of the good wishes and embraces of the adults, of the clink of champagne glasses. The moment is overlaid with the later repetitions of this sequence that took place over many years following the same pattern, with the same participants. My brothers and I must have run back out into the street immediately afterwards. I see my father stepping out of the house with some of the male guests—they all wore hats, some of them had put up their collars—taking the rockets from my brother and sticking them in the bottles standing ready. There would be, as I found out later on, enough rockets to fill the row of bottles five, maybe six times over. A short while later, when everything stood ready, my mother came outside with the other women. The first rockets were lit on the adjoining plot of land. The sound of laughter and the judder of the last train reached over to us.

My mother wore a short, light-colored musk beaver coat, and her midlength blond hair peeked out from under an electric blue hat she’d knitted herself. My brothers were fighting over the lighter that my father had given them. Both of them wanted to be the first to light a rocket. My mother saw that they wouldn’t reach a compromise, also saw that I stood by more or less helplessly. She pulled out her own lighter and a pack of Kim cigarettes from her coat pocket, a white pack with a red, orange and yellow wavy strip under the logo that was supposed to represent a trail of smoke. I knew the brand, of course; my mother smoked ten or fifteen of these cigarettes a day at the time. Later, with mounting depression, her cigarette consumption also rose, and she changed brands.

She pulled out a cigarette, lit up and held it out to me like a treat being offered through the cage bars of a snappy animal. With a slight raise of her chin and without saying a word, she invited me to take the burning cigarette and light a rocket with it. It wasn’t the first time I’d held a cigarette in my hand. The chocolate cigarettes were especially prized by children of my generation because they were vital (and certainly more important than pistols or hats) for acting out scenes from Westerns. In addition, I’d frequently pull out a cigarette from the cup decorated with an iridescent green velour brocade that was always well stocked on the living room table. I’d stick the cigarette between my lips and suck, sort of aping Aunt Anna, who would pay me to play cards with her whenever she was visiting us in Cologne. Although I’ve never smoked “cold” in adulthood, not even put a cigarette in my mouth on a moving train or exiting a university building in anticipation, I can still remember to this day the herbal-ethereal flavor of the cold tobacco reaching my mouth through the filter. But it was the first time I’d ever held a lit cigarette in my hand.

I accepted it with a reverence that was felt perhaps more truly and deeply than the humble spirit required of me a few years later at my first Communion. I held the cigarette at the very end of the (white) filter, turned around and walked the few steps to the bottles, keeping my eyes fixed on the tiny ember already hooded by white ash. When my father gave a military gesture to signal the launch, I squatted sideways in front of a bottle, half averting my face, and guided the spark with an outstretched arm and squinting eyes towards a fuse. I was so fascinated by the cigarette and its possibilities, I was so amazed by the fact that something could be set alight by such a weak glow, that I didn’t even pick the biggest, most beautiful, most colorful rocket. I was shaking. I poked the spark at the strangely stiff fuse only a few centimeters from the neck of the bottle. The ash flaked from the cigarette, and I tried again and again, after my mother encouraged me with a nod, until finally, finally the fuse flashed with a crackle, and my father pulled me away from the bottle by holding me tightly under my arms and lifting me a little into the air.

I forgot to watch the rocket and looked at the cigarette that I still held between my fingers like something dangerous and magical. The spark had all but gone out from poking it at the fuse. You have to take a drag on it, my mother said out of the half darkness, otherwise it’ll go out. Of course, I have to take a drag on it. I’d seen the adults—who practically all smoked—do it often enough. My father still smoked at this point too. He worked in his study cut off on the ground floor of the house, and while he worked thick smoke would roll out from under his door and rise into the other levels of the house. When I was three or four, I seem to remember thinking for a while that smoking was his actual job.

My beautiful, taciturn mother stood on the pavement in the cold night with her hands in the sleeves of her fur coat and gave me a half-sad, half-amused look. You have to pull on it, she said again. I pulled. What else could I have done? I took a drag on the cigarette and felt the smoke, which I had imagined to be warmer, fill my mouth, rise into my nose and lie burning on my eyes, which I had to close, while I snorted out the smoke in shock. But before I’d completely released it, I had to breathe in, and so I started coughing on the pavement with burning, running eyes until my mother banged me on the back. My reaction unleashed a wave of merriment among the drunk adults. But on hearing the expelled laughter, I became, in the strictest sense of the word, myself again. Maybe, as I believe today, I became myself for the very first time. My first thought was that the cigarette could have fallen out of my hand during the coughing fit, and I registered with conscious pride that this hadn’t happened. Then I noticed a tingly, acidic, unfamiliar feeling in my stomach. I felt dizzy, but it was as if the mild nausea that I’d detected with an almost scientific interest hadn’t seized me, but rather a living entity within me; something—and I have to take great care not to speak of it too favorably—that I could claim as part of myself. I believe that in this moment I perceived myself for the first time and that the inversion of perspective, this first stepping out from myself, shook me up and fascinated me at the same time. And I believe that this first feeling of well-being triggered by nicotine—my first head rush—was forevermore entwined with this fascination.

I was confused, stunned, happy, thrilled. Blood pulsed at my temples. There wasn’t any time to take in any impressions or glory in the new—perhaps not even yet understood as new—feelings I’d just experienced due to the pressures of brotherly rivalry and my own childish greed for experiences. I quickly pulled myself together. I surveyed the situation, saw that my brothers for their part were loudly and agitatedly begging for cigarettes. So we can light the rockets. My mother once again pulled out her Kims from her pocket, lit two cigarettes at the same time and handed them out to them without a word. I don’t know how my brothers fared; I didn’t ask them afterwards and haven’t to this day. I didn’t know for a long time whether my brother Stefan, who was ten years old and who was considered a difficult child, had already smoked or whether this cigarette constituted just as an intense, wholly new experience for him as it had for me. When I sent him a short email asking him to confirm some dates for the book concerning our great-aunt, when she got her pension and when she took her world trip, he wrote without being prompted that his first cigarette was a Lux that our grandfather had given him on a camping trip in the Bienhorn Valley near Coblenz. I had always dreamt—as I already mentioned—of smoking a cigarette with my grandfather, and my brother, I now read, apparently did precisely that. And not just any cigarette: he smoked his first with him, the first, the most important cigarette of his life! Our grandfather Karl, whom we called Chattering Karl due to his taciturnity, gave him this Lux. Presented to him, I think, as if it was the greatest gift that a person can give someone. Presented wordlessly. And it was long before my mother drew her pack of ladies’ cigarettes from her musk coat. The most casually made gestures are also always the most beguiling.

I took another drag on my Kim. Now that the initial dizziness had subsided, my awareness took on a new, never before recognized clarity; it was as if a curtain had been pulled back to let in a breeze, a fog bank had been blown away. Before me lay a wide, sharp landscape all the way to the horizon. It was my inner world—my feelings and thoughts—that had taken on distinctive contours in a constellation that I found beautiful. I felt a mental tingling, a delirium, and I remember that my brothers and the adults present, even my parents, appeared strange to me. Triggered by the nicotine penetrating the mucous membranes in my mouth and nose, entering my bloodstream and within a few seconds shooting into my young, malleable brain, I felt and saw, perhaps for the first time, a great experiential context. Life was no longer composed of individual moments, of wishes and disappointments, that pass by indiscriminately and in quick succession; I not only saw images, not only heard single words or sentences, but also experienced an inner world. In this manner, I was offered for the very first time an experience that was narratable. This is precisely why I can remember this night with such completeness, precisely why I can write it in this form.

A rhythm, a cyclical time pattern that accompanies me to this day must have also begun to overlay all my experiences after those first drags. The chemical impulse initiates a phase of raised consciousness that makes way for a period of exhausted contentment. Immediately after the first drags an almost unshakable focus on what’s essential, on what’s cohesive and relatable, sets in. I often have the impression that I can easily link together mental reactions to my environment that serendipitously arise from one and the same place in the cortical tissue during this phase. This results in associative and synesthetic effects that help me to remember, along with the dreamlike logic that is the basis of my creativity.

Even though I’ve not smoked for a long time, I still think and work in a constantly repeated rhythm of around half an hour. This consists of an inner impulse, a still physical but now also an endogenous stimulus, and a phase of many-stranded consciousness that levels out in a motion that seems elemental and natural and always at precisely the right time when my body and my spirit can’t go on—like a wave smoothly rolling onto a beach. To be more precise, I should really let go of the conjunction, dispel with the old dichotomy and write my body, my spirit, as if they were two words for the same thing, as they are inseparable in moments such as these. I experience the mental processes under the influence of nicotine as something decidedly corporeal—they are powerful or weak, sleek or angular, cold or warm, light or heavy—whereas I experience the body as a mental phenomenon, as something to be understood, learned and remembered.

At the end of this awareness phase, a quick half hour, I feel the incoming (initially only impending) withdrawal phase that I’m not prepared to enter. I defeat the renewed impulse, as I no longer smoke, from my own willpower, from an inner, undoubtedly exhaustible reserve. A smoker would now reach for the next cigarette. Sometimes I just lean back in my chair and turn my attention to the inner processes as set out above. I consider them and wait until what my therapist describes as cravings and what in my Lower Rhenish youth was called Schmacht—profound hunger—have passed. It lasts no longer than two minutes.

* * * *

I took a few more drags on my cigarette that New Year’s Eve and lit rockets with increasing assurance. I’d soon learnt to close up the epiglottis in my mouth when pulling in the smoke, protecting me from more coughing fits and the derision of the adults. In the years that followed, we children were given one or two cigarettes every New Year’s Eve (depending on how much money my father had spent on fireworks), and it wasn’t long before my thrill of anticipation for the cigarettes far outstripped my anticipation for the fireworks. When I see a firework, I still get the taste of this long, thin Kim on my tongue and remember with great warmth the sad-beautiful eyes of my mother, who handed me cigarettes as if they were something sacrosanct.

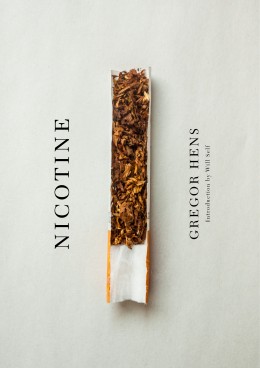

From NICOTINE. Used with permission of Other Press. Copyright © 2017 by Gregor Hens.