Naked Ladies and Weird, Invisible Men

What Carina Chocano Learned from her Grandfather's Playboy Collection

I learned about sex from Where Did I Come From? but I learned about sexiness from my grandfather’s Playboys and Bugs Bunny in drag. I gathered, from the book, that sex was an awkward thing that happened when a lumpy man was feeling “very loving” toward a lumpy lady and wanted to “get as close to her as possible.” From Playboy, I learned that sexiness was naked ladies and weird, invisible men.

My grandparents’ house was built in the mid-1950s and looked like the set of a Pink Panther movie. The den, in particular, showcased the kind of rakish, cosmopolitan masculinity that was cool at the time. Perhaps there was a time when my grandfather hosted regular poker games with other guayabera-wearing, Brylcreemed, sun-damaged men in white socks with sandals gathered around the green-felted card table, but by the time I came along, he was down to one. Tío César was a retired navy admiral whose gentle mien, bulbous nose, and severe vision impairment recalled a beatific Mr. Magoo. Another interesting thing about him was that he had lost his vocal cords to cancer and relearned to speak by gulping down air and burping out words. (It’s called esophageal speech. He taught us to do it.) By the time I came along, the den was not a social space so much as a shrine to the persona my grandfather had created for himself, with Playboy as his guide.

My grandfather collected Playboy magazines. I don’t mean he saved every issue; I mean he saved every issue, had them bound by the dozen into leather-bound annuals with gold-embossed spines, and arrayed them on a low shelf behind the poker table like a set of handsome encyclopedias. They imparted a pervy yet learned vibe to the room that offset the lowbrow ribaldry of the framed cartoons by the mirror-backed bar, featuring scenes of sexy nurses and sexy secretaries being sexually harassed. There was also—my former favorite—a cartoon of a man flushing himself down the toilet over a caption that read, “Goodbye, cruel world.” The nurses and doctors in the framed cartoons in my grandfather’s den looked like creatures from two different planets (Toad Mars and Bimbo Venus), but it was the pink, chubby, bald, and frizzy-haired illustrated couple in Where Did I Come From?, slotted together like a hippie yinyang with little red hearts floating up from their naked embrace, that struck us kids as strange and unfamiliar; a little too fraternally similar for comfort.

“The Playboy collection was a museum of girls, a taxonomy of girls. The pictures fascinated me and filled me with ontological terror at the same time.”

This is how, in elementary school, I came to be sentimental about my grandfather’s nudie magazines. Ribbon pigtails (like mine!), had a strangely static and hermetic quality that made the girls’ nakedness look somehow artificial. They made me think of the taxidermied animals at the natural-history museums in Chicago and New York. It was like they were specimens, more lifelike than alive. That they were stripped of their clothes didn’t bother me as much as that they were stripped of all context. They were isolated and frozen in time. Even the outdoor shots seemed to be taken behind glass. The girls’ accompanying biographical squibs only added to this impression, resembling the plaques next to museum dioramas detailing an extinct animal’s name, geographic provenance, “statistics” (height, weight, bust, waist, and hip measurements), and dietary patterns and mating behaviors, or “turn-ons” and “turn-offs.” The Playboy collection was a museum of girls, a taxonomy of girls. The pictures fascinated me and filled me with ontological terror at the same time. I knew, because everybody knew, that only girls were “sexy,” that “sexiness” was girls—it was exclusively female. This confused me, so I kept going back to the magazines, trying to figure it out. It made me uncomfortable in ways I couldn’t begin to express.

The models’ aura of stuffed-bunny obliviousness, by the way, was precisely the vibe Playboy was going for. In 1967, Hugh Hefner told the Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci that he’d called the models Bunnies because the rabbit, the bunny, in America has a sexual meaning; and I chose it because it’s a fresh animal, shy, vivacious, jumping—sexy. First it smells you, then it escapes, then it comes back, and you feel like caressing it, playing with it. A girl resembles a bunny. Joyful, joking. Consider the kind of girl we made popular: the Playmate of the Month. She is never sophisticated, a girl you cannot really have. She is a young, healthy, simple girl—the girl next door . . . We are not not interested in the mysterious, difficult woman, the femme fatale who wears elegant underwear, with lace, and she is sad, and somehow mentally filthy. The Playboy girl has no lace, no underwear, she is naked, well-washed with soap and water, and she is happy.

I didn’t read this as a kid, of course, but I still think the message got across. Playboy’s “idea of woman” was a naked fairy-tale princess: a young, dumb, defenseless, trusting, easily manipulated woodland creature. She gave herself entirely because she was too inexperienced to know any better. She was a fresh animal, well washed with soap and water. She could not learn, grow, or change. She could not really exist in a temporal sense. All she could do was to try to preserve and display herself. Experience made her difficult. It got her banished to her witchy cottage in the forest. She had to remain a dumb bunny, an unconscious body, frozen in time and preserved in amber, for as long as she could in order to survive. The “sexy lady” is the only kind of lady that openly exists in the sunshine of the symbolic realm. She is the only kind of lady that warrants being looked at, paid attention to, or acknowledged. In order to be listened to, a lady should be nice to look at. There should be no doubt as to her sexual desirability, but this will undermine her argument, no matter how sophisticated. We are not interested in sadness, sophistication, or experience. We secretly believe that female subjectivity is filth.

When you are a kid—when I was a kid, anyway—you believe in superlatives and data, and find a great deal of comfort in this orderly vision of the universe. So you set out to rank and rate and sort and classify everything you can. When I was in first and second grade, I thought that the Miss America, Miss World, and Miss Universe pageants were actual statistical rankings of the prettiest women in the country, the world, the universe. (I wasn’t sure how Miss Universe could claim the title without competing against aliens from other planets, but I was willing to suspend my disbelief.) I understood that being pretty wasn’t the most important thing, as no doubt some adult had dutifully informed me at some point, but it was obviously the only thing that anybody cared about where girls were concerned. You surmised this just by existing. Being the prettiest was the pinnacle of womanly achievement. It ranked you, if you were pretty enough, as the number one girl in the universe. Yet if prettiness made you visible, it also made you strangely invisible. It made you recede into an undifferentiated, standardized mass.

“Playboy’s ‘idea of woman’ was a naked fairy-tale princess: a young, dumb, defenseless, trusting, easily manipulated woodland creature.”

Before Hugh Hefner came along, porn was furtive and hidden. After Hefner, it was everywhere; mainstream, pop, classy, cool. Hefner considered that his big innovation was realizing that Playboy wasn’t actual porn so much as lifestyle porn. He wasn’t selling pictures of girls, he was selling a particular male identity via consumption of girls as consumer objects. This identity was similar in many ways to the identity being sold to ladies in ladies’ magazines, only with naked ladies themselves as the expendable products whose constant consumption would bring happiness. This is why Hefner reportedly worried less about competitors like Penthouse and Hustler than he did about “lad mags” like Maxim and FHM.

For all their surface differences, the Playmates didn’t suggest individuality so much as variety, an endless cornucopia of consumer choices. As a second-grader, I could fully grasp the orgiastic appeal of beholding something like this. The pleasure of positioning oneself in front of a new 64-color crayon set, complete with built-in sharpener, was impossible to overstate. Like casting a proprietary eye over the display at Baskin-Robbins, it was a heady feeling that quickly gave way to entitlement. I felt nothing short of outrage when the number of flavors fell short of the promised 31. That I always chose the same flavor anyway, and wore out the same-color crayons while barely touching some of the others, was not the point. The possibility of infinite choice was the point. The too-muchness was the point. Knowing the Burnt Sienna was there at your fingertips. Empowering you was the point.

Of course, looking at naked girls in Playboy didn’t make me feel powerful. On the contrary, it made me feel like I was getting a glimpse into a parallel universe where I was at once invisible and excruciatingly visible, negated and exposed. There was no inverse equivalent. I was unaware that just around that time, an academic named Laura Mulvey was coining the phrase “the male gaze.” That language would remain unavailable to me for another two decades. At the time, all I had to help me make sense of it were things like the Frog and Toad story “Dragons and Giants,” the one where Toad gets separated from Frog and runs into a giant snake at the mouth of a dark cave, and the snake sees him and says, “Hello, lunch.”

__________________________________

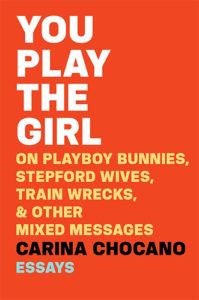

Excerpted from YOU PLAY THE GIRL: On Playboy Bunnies, Stepford Wives, Train Wrecks, & Other Mixed Messages by Carina Chocano to be published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in August 2017. Copyright © 2017 by Carina Chocano. Used by permission.

Carina Chocano

Carina Chocano's work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New York Times, New York, Elle, Vogue, Rolling Stone, The California Sunday Magazine, Bust, The Washington Post, Vulture, The Cut, GOOD magazine, Texas Monthly, Wired, The New Yorker, The New Republic, and many others. She has been a film and TV critic at The Los Angeles Times, Entertainment Weekly, and Salon.com. Her book You Play the Girl will be published by Houghton-Mifflin Harcourt in August 2017. She lives in Los Angeles.