More, More, More: Why We Love Author Documentaries

Jonathan Russell Clark Considers New Docs on Joyce Carol Oates, Stephen King, and Tom Wolfe

Writers are elusive creatures. For all the thousands and thousands of words they publish—describing, at length, what they see in the world—we readers can’t seem to leave well enough alone. We gulp down interviews and profiles, attend readings and talks, and watch documentaries and biopics—we always want more.

Why do writers fascinate us? What more do we truly want from them? And if we are in fact given intimate access to them, what can we learn? And do the things we learn add to our understanding of the author?

A recent spate of documentaries on writers serves as an excellent way of diving into these questions, especially because the three films under consideration here—Joyce Carol Oates: A Body in the Service of Mind, King on Screen, and Radical Wolfe—each take a different approach to their subjects. The Joyce Carol Oates documentary is a portrait, one in which Oates herself takes part—her participation is, indeed, the only reason it exists. King on Screen, on the other hand, focuses on the cinematic adaptations of Stephen King’s many novels and stories, but King did not participate, so it’s the filmmakers behind the movies who collectively create a mosaic-like celebration of King’s formidable oeuvre. As for Radical Wolfe, well, its subject, Tom Wolfe, died in 2018, so it’s much more of a retrospective assessment, in this case from the point of view of Michael Lewis, on whose 2015 Vanity Fair article the film is based.

Each approach has its own limitations, but there are also moments of genuine insight and an all-around love for literature that is wonderfully infectious.

*

Joyce Carol Oates: A Body in the Service of Mind

Stig Björkman, the filmmaker behind A Body in the Service of Mind, clearly adores his subject as a fan and a friend. He admits to asking Oates to do the film for many years before she finally acquiesced. As in his previous career-spanning interview-profiles of Woody Allen and Ingrid Bergman, Björkman only wants to portray Oates in the most glowing light. His aim, ultimately, is canonization, which he attempts to accomplish by connecting Oates’s novels to historical events (the Detroit riots in 1967 leading to 1969’s Them, for example) and extrapolating from each title the big American themes all great novelists are supposed to undertake (race, gender, class, etc.). While these aspects of the film waver in their efficacy, what works best is the contrast between the Oates being interviewed with the many versions of herself shown in archival footage from throughout her 60-year career. Seeing Oates in the 1960s and 1970s—looking young and elegant, sure, but also demure and deferential—reminds us just how many eras she has lived through and written about.

Oates has probably published too many books, which has diluted her reputation as a great American writer. Literary legacies often benefit from scarcity, as it’s much easier to rally around a single work than it is to extol consistency across 200 books. We want our greatness collapsed into something manageable, something we can point to and say, Yes, that’s greatness. But Oates has produced such a vast catalogue that the sheer size of it overwhelms.

Moreover, Oates’s use of social media has also put a damper on her reputation; she’s viewed now as an ornery coot with hilariously misguided takes. It’s too bad. I remember reading her 2017 novel A Book of American Martyrs and wondering why its arrival wasn’t a bigger deal—it’s a brilliant and ambitious novel that captures much about America’s complex history with abortion. But consider: the same year as A Book of American Martyrs, Oates also released a collection of stories; the year before, she published a story collection, a novel, and an essay collection; the year after, she brought out two story collections and yet another novel. It’s no shock, then, that a 700-page masterpiece on a hot-button American subject could slip through the cracks of Oates’s prodigious prolificacy. I hope, at the very least, Björkman’s loving tribute to Oates will rekindle people’s interest in her writing and show that she is much more than a crammed bookshelf or a goofy tweet.

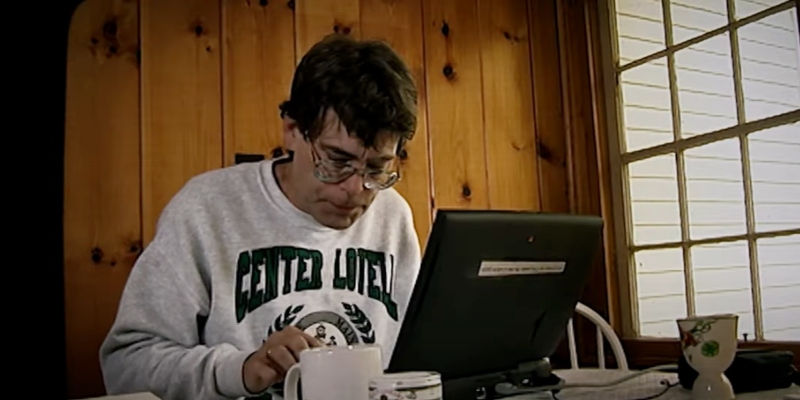

King on Screen

Speaking of prolific, Stephen King is one of the few American authors whose output nearly matches Oates’s, and as time passes I think the sheer volume of King’s work will have a similar effect on his legacy. But while King doesn’t have a singular masterpiece to point to, his reputation is undergirded by Hollywood’s rampant ransacking of his fiction. King on Screen, directed by Daphné Baiwir, intends to celebrate the many cinematic adaptations of King’s work, most notably by interviewing the very filmmakers responsible for those movies: Frank Darabont (The Shawshank Redemption, The Green Mile, The Mist), Mick Garris (The Stand, Sleepwalkers, Ride the Bullet), Taylor Hackford (Dolores Claibourne), Mike Flanagan (Doctor Sleep, Gerald’s Game), and others discuss their love for King’s stories and their experiences translating them onto the screen.

But a funny thing happens in King on Screen: it becomes a little confusing just what is being celebrated. At times, King’s novels get conflated with the movies based on those novels, so when the interviewees are discussing, say, Brian De Palma’s 1976 adaptation of Carrie, King’s first novel, all of their commentary is visually supported by clips from the movie, as you would expect—but oftentimes Flanagan or Darabont will interchange talking about the novel and the film. After all, De Palma’s film, though fairly faithful to the novel, was written by Lawrence D. Cohen, who isn’t mentioned at all. I understand that the premise of the documentary is filmmakers explaining what makes King’s work so adaptable, but at times the distinction blurs, and the intended exploration gets muddied.

The film’s structure is already a bit amorphous, moving around in time and tone in a not wholly comprehensible way, and it goes on just a little too long. Also, some major figures in the King Cinematic Universe are notably absent from the cast: Rob Reiner, who made two of the greatest King adaptations in Misery and Stand by Me; Tommy Lee Wallace, director of the classic miniseries It, which features, in Pennywise the Dancing Clown, King’s most iconic creation, and in Tim Curry’s performance, the most terrifying villain in made-for-TV history; John Carpenter, who made Christine; and De Palma. George Romero, Tobe Hooper, and Stanley Kubrick all have the excellent excuse of being dead.

What makes King on Screen a worthwhile watch, though, is hearing these talented artists rhapsodize about the impact King’s work has had on them. Frank Darabont, for instance, agreed to make The Green Mile before King had even finished writing it (the novel was published in short installments). Mike Flanagan provides keen insight when talking about why he kept on reading King’s It as a young boy even though it scared the hell out of him:

But I cared so much about the Losers Club, I cared so much about these beautifully rendered characters that I had to keep reading. By the end of it, I realized that he had created an opportunity for me to learn how to be braver in very small increments. Just to finish a chapter, or eventually to finish the book. And that became a muscle I tried to exercise as I got older, and what I think really horror is all about: it’s exercise for courage. In the same way that we go to the gym to try to get stronger physically, horror movies and horror stories can help us practice being brave for a very short amount of time in a completely safe space.

Horror stories as “exercise for courage” is a beautiful notion, and it makes King’s reign as America’s most popular author seem sensible, as much of American life anymore resembles the kinds of stories that King—and his coterie of sycophantic directors—tell.

Radical Wolfe

When Tom Wolfe died in 2018, he was a man out of time. Once the most celebrated writer in the country—a truly famous figure—Wolfe was, in those final years, a relic of a bygone era. But he was an important writer who had one of the most distinct styles of his generation. Of any generation, really.

I happen to be a Tom Wolfe junkie, so I was very much looking forward to Richard Dewey’s exploration of this fascinating person. Radical Wolfe does indeed cover most of Wolfe’s career—the hits, at least—and touches all the things you’d most likely cover. Moreover, it doesn’t shy away from the problematic elements of Wolfe’s creative enterprise—namely, his seeming disregard for the feelings of his subjects, his reductive and racist treatment of non-white characters, etc. But at barely 75 minutes, Radical Wolfe doesn’t fully do justice to a monumental force in American letters. Then again, maybe it’s an impossible task. At any rate, I wanted—as we always do with writers—more, more, more…

For whatever reason, the film is based on the aforementioned Vanity Fair article by Michael Lewis, the bestselling author of The Blind Side, The Big Short, and Moneyball, who essentially navigates the direction of the documentary. I don’t have anything against Lewis, but his constant presence inevitably prompts the question: why should I care what Lewis thinks of Wolfe? Gay Talese, Gail Sheehy, Lynn Nesbit, Christopher Buckley, and Jamal Joseph—all of whom are featured—these are the people I want to hear from! I can’t get enough of Talese describing the Wolfe he knew over their six-decade-long friendship, or Jamal Joseph explaining how the Black Panthers reacted to Radical Chic when it was published (“The broad reaction in the Panther party,” he says, “was that, you know, this dude is trippin’”).

The novelist John Irving provides the biggest laugh of the film, when, in an interview from the time when Wolfe’s novel A Man in Full was published, he complains about how much he hates Wolfe’s writing: “If we had a copy of any Tom Wolfe book here, I could read you a sentence that will make me gag. I don’t know what it’d do to you, but it would make me gag. If I were teaching fucking freshmen English, I couldn’t read that sentence and not just carve it all up.” I wish there had been more time spent with these characters and less with Lewis, whose centrality feels arbitrary.

My absolute favorite moment, though, is when Junior Johnson, the stockcar racer who Wolfe mythologized in one of the early features that made him famous, is reunited with an aging Wolfe after so many years. “The Last American Hero,” tracing Johnson’s rise from whiskey runner to legendary racer, appears in Wolfe’s first book, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, and to see the two of them together—once brash young men of daring abandon—now smiling old geezers. How impossible their younger versions would find such an image! Not vibrant, vital, eternally youthful me hunched over with wrinkly skin and white hair! Not me saying, “As I live and breathe” and meaning it!

Obviously, as a result of writing this piece, I’ve reread some classic Wolfe, and his infectious style charged its way into my prose.

But perhaps this is the optimal result for documentaries about writers: that for all their pontificating about what makes Oates or King or Wolfe great, the best—and only—way to learn about the mysterious alchemy of literary brilliance is to go back to their books and accrue, word by glorious word, the answers you’re looking for.

Jonathan Russell Clark

Jonathan Russell Clark is the author of Skateboard and An Oasis of Horror in a Desert of Boredom. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, L.A. Times, Boston Globe, and Esquire. He's also a columnist for Tasteful Rude.