Mitchell Jackson on John Edgar Wideman and the Beginning of Black Lives Matter

In Conversation with Lorraine Berry on the Legacy of the Till Family

On August 24, 1955, Emmett Till, a 14-year-old Chicago boy who was visiting his relatives in Mississippi, went into a small grocery store to buy bubble gum. Three days later, his brutalized body would be pulled from the Natchez River. Till, who was black, had allegedly “flirted” with the white woman who owned the store and a mob of white men destroyed his body as payback.

Till’s mother, Mamie, insisted that Emmett’s body be displayed in an open casket so the world could see what the men in Mississippi had done to her boy. She wanted the world to know what racism did to children, how hatred based on skin color could lead to a child’s face being mutilated so horrifically that he was unrecognizable.

Emmett was identified by the ring he was wearing. The ring had belonged to his father, Louis Till, who had also suffered an unjust fate at the hands of white men. In 1945, Louis Till was hanged by the US military, having been convicted of raping a white woman in Italy.

John Edgar Wideman’s latest work, Writing to Save a Life: The Louis Till File is an exploration of the life of Emmett Till’s father. Wideman studied Till’s military file and trial transcript for years, and journeyed to the scene of the alleged crime in Italy and also to the senior Till’s burial place in France, in order to give Louis Till back the life that the army took from him.

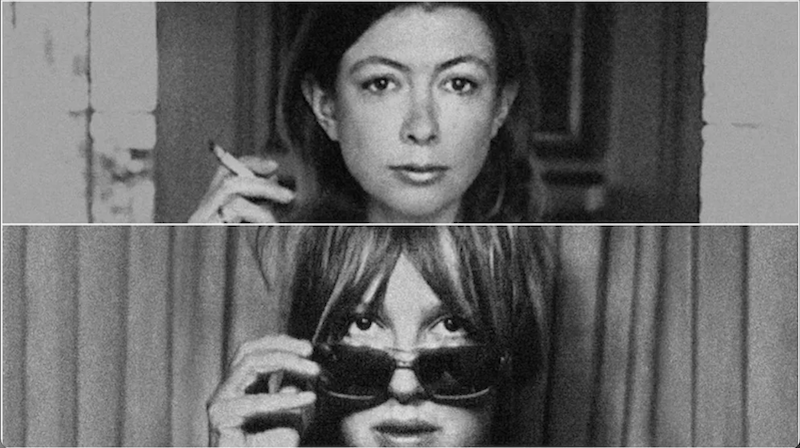

In a recent conversation, LitHub contributor Lorraine Berry and author of The Residue Years Mitchell Jackson discuss the book. Both read the work before and after the election, and found that after the election, many of Wideman’s points about how nonfiction writers can find moments to re-claim the truth felt even more relevant given the dawn of a presidency that has already defined itself by its “post-truth” belief system.

Lorraine Berry: One thing I’ve noticed since the election is that I’m finding it difficult to put words and thoughts together. Were you as surprised as I was by the election?

Mitchell Jackson: Did you see the SNL sketch with Chris Rock and Dave Chappelle? Where the white guys are watching the election returns and they keep saying that it will turn around? That was me on election night. I stayed up until 3 am. I even watched Donald Trump’s acceptance speech. It was like someone said to me last week: “I went to bed when it was 2016, and when I woke up, it was 1953.” And I told him that it had been 1953 when he went to bed, and 1953 when he woke up, he just hadn’t realized it. But those feelings about race had always been there.

Race is built into the bedrock of America. The election results proved that. We’ve known for a hundred years that race is a social construct, that it’s an irrational thing to cling to whiteness, and yet women voted for whiteness over their gender. People chose their color over rational things when they voted for Trump.

LB: Do you think that John Edgar Wideman believes in Louis Till’s innocence?

MJ: It isn’t clear whether Louis Till is guilty when you read the book, but what is clear is that he didn’t get a fair trial. They hanged him for something that if he had committed it in the United States, he wouldn’t have been executed for. It was as if they were creating a punishment they thought was enough for the crime in Italy.

LB: Emmett Till’s father is a difficult character to relate to.

MJ: It’s one of the achievements of the work. John Edgar Wideman does a tremendous job of giving Louis Till’s life a narrative. He makes him empathetic, and Mamie empathetic. He shows us Louis’s life with his mother, and when his father leaves. And it doesn’t excuse Louis for beating Mamie, but it shows us that Louis was a flawed person when he did it.

When I was serving on a panel last week talking about prisons, we were talking about rehabilitation, and one of my fellow panel members said that it is troublesome to think of prisons in terms of rehabilitating someone because many people who go to prisons were not “habilitated” to start with. Louis Till had nothing. He didn’t have a father figure or anyone to show him right from wrong. He didn’t want to go into the military. John Edgar Wideman shows us these things about Louis Till.

LB: We are now dealing with a President-elect who has a very elastic version of the word “truth.”

MJ: Wideman talks about truth in the book when he says that “truth is what power is willing to accept.”

LB: Yes. There’s a sense of the truth that runs through the book that the truth of the narrative is dependent upon who is in charge of the narrative. It reminded me very much of my experiences in the archives, when I realized how many layers there were between me and the person being questioned in a trial. But Wideman does this interesting thing, especially when he’s talking about the questioning of Junior Thomas, who testified against Louis Till. He actually decides what happens when they were speaking to Thomas, when they convinced Thomas to tell them “what happened.” He writes:

I was not in the CID lieutenant’s office. Nor anywhere else in the DTC. I’m reporting imagination as fact. Unscrupulous as any army investigator. Worse because I claim to know better. Want my fictions to be fair and honest. As if that desire exempts me from telling truth and only truth. The United States Army’s not exempt either, even if the army’s duty to win a war and keep peace after war a more credible excuse than mine for bending facts, inventing truth.

How do we as nonfiction writers and writers respond to this now that we are increasingly called upon to oppose these untruths by authorities? How do we fight these untruths from these corrupt authorities?

MJ: Yesterday, I saw a clip of Denzel Washington speaking about the media. He said, “If you don’t read the news, you’re uninformed. If you do read the news, you’re misinformed.” And then he charged the journalists: “Your job is to tell the truth. Not to be first. Not to report the most sensational information. Not to do the due diligence in vetting the information. You need to report the truthful information as you understand it.”

I think that is the charge of being a nonfiction writer. I think Wideman’s imagination is to fill in blanks so that he can get at the deeper truth even if it’s him having to imagine being in that room, or imagining why the investigators might have fabricated parts of the story. I see him using imagination to uncover a deeper truth rather than to obscure a truth. And I think that maybe some of the more sensational or more biased reporting from the election was meant to obscure facts rather than to present them in a way that gives us an opportunity to consider our world in a way that doesn’t feel coerced.

I see his truth as being more moral than I would see the investigators’ truths who wanted to get a conviction fast.

LB: I’ve always heard that the job of the press is to “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable,” and I think the press lost their way. They’re doing a lot of punching down. I’ve been disturbed by the New York Times because it feels as if it’s trying to normalize fascism.

MJ: Except for Charles Blow…

LB: Absolutely. Who has been speaking truth to power.

I agree with you that Wideman is investigating these silences, and he is filling in these blanks. Do you think that Wideman is in a unique position to do this? Do you think there are other writers who could have looked at this material and done justice to Louis Till’s story?

MJ: I think there are other writers who could have done it. But I think Wideman is able to because he’s in the position of being the same age as (Emmett) Till and that’s the era of the story. I think one of the things that Wideman brings to it is unassailable credibility in the literary world. Even if another writer had thought it up, they’re starting from a deficit. They haven’t earned that kind of respect. You’re willing to give him the leeway to explore in a more creative way than you would someone else. You might lose patience with them. I think he has the ethos. We believe his motivation to begin with. He talks about how difficult the project was. He talks about how it failed in some ways, how he intended it to be something else. He’s honest about his early life. He mentions his son and his brothers, so I think all of those things help to build an ethos that is necessary to investigate this story.

LB: Wideman as a writer has this authority in the writing world that he’s able to claim in writing this book. One of the things that I noticed as I was reading is that when he’s looking at the white officers who are questioning these men who had been brought in front of them, he starts looking at gestures that pass among them—the winks, and the nods, the things that went unsaid—and it’s almost as if he’s performing this anthropological analysis of whiteness, all of these gestures that pass among these white men. When people like Clifford Geertz did this kind of thick description with indigenous peoples in other countries, they were seen as exerting this power over their subjects. Do you think that Wideman gets some kind of power over these white officers in being able to write this way?

MJ: I think he’s exerting power in the sense that all writers get to exert power over their subjects or the characters they create, so I do sense him doing that. But I think of it as more trying to get back to the truth: how does power communicate to power when it has to be tacit? And he’s using his imagination to arrive at a fuller truth then just “they had this investigation and here’s the verdict.”

One of the things I admire is that he will tell you when he’s imagining, especially when it’s something important like that. “I was not in the room, but here’s what I imagine these men were doing.” Because they had to have some kind of non-verbal communication. So I don’t know if he’s exerting power over whiteness or he’s just exerting power over the subjects that he’s writing about. I probably would argue for the latter.

LB: One of the things that I really admire about this book is that even as he’s filling in these blank spaces, Wideman maintains his discipline and still refrains from constructing a redemption narrative.

MJ: I think that goes back to “what is the truth?” The truth is there was no redemption in this story. So to claim it as a redemption story would be to manipulate the truth as it is and probably as he saw it. Where was the redemption in a father dies and a son’s murder? I appreciate that he doesn’t try to turn this into a happy ending.

LB: Americans love their redemption stories.

MJ: Louis Till had a tough life, and he was executed for a crime he probably didn’t commit. And then his son died a horrible death and there was no redemption in that.

And in the ending, not even giving a sense of a real closure. It’s not over. And I think you can see that when we talk about the election, and when we talk about Black Lives Matter. Sadly, this kind of suffering is evergreen.

LB: Let’s talk about Mamie Till.

MJ: For me, the Black Lives Matter movement begins with Mamie Till when she insisted on an open casket. She wanted people to look at her son, her boy, and to see that he was a child just like theirs. I think we lost track of the movement until Trayvon Martin’s and Eric Brown’s families came forward.

LB: Her gesture of saying, “Look what you did to my son. This isn’t some fetish object,” was so powerful. Is there a word for Mamie? I hate the word “dignified,” because it’s the word white folks use to describe black folks who they think are “acting white,” or whatever effed-up concept they have in their heads. Is it courage? There’s something so solid about her.

MJ: I would just call her a brave, brave mother. She’s protecting her son, not only in life, but in death. That’s a mother. They love their children before the challenges of the world and they stick with them. But I also think it was brave, especially at the time. Mississippi. Chicago. To do what she did took a vast amount of courage.

Even now, the activists of Black Lives Matter don’t really see their lives in danger, not while they’re being active. Maybe if they’re alone. But I don’t think there’s been an instance where a protester or an activist was murdered in the course of being an activist for Black Lives Matter, which was perfectly possible during the era of Mamie Till. Her courage is… it’s not fair to compare. But if you know that you can die—he talks about her getting death threats—those weren’t “threats,” they were real. I don’t know how I would comport myself if in order to vindicate my son’s integrity I had to face constant threats. Because at this point, it’s really philosophical, right? There’s nothing that she could do to bring him back, so she had to ask herself, Do I take this moral position or do I protect my life?

LB: What is the responsibility for writers for the next four years?

MJ: The thing that I’ve been working on, and thinking about how does it speak to what is happening with the coming Trump regime is that the writer’s job is to take the things that they are passionate about and to investigate them and then to write about that investigation.

I don’t think that a writer who isn’t passionate about Black Lives Matter that suddenly it’s their job to write about that issue, because then the writing suffers if the passion isn’t there. It’s still the job of the writer to pick things that they’re passionate about and then to present that story with the least imputation, bias, and subjectivity as they can.

If you’re not passionate about something, you’re more easily pushed off what you’re working on. It’s too easy to get discouraged.