Life Beyond Act One: Why We Need More Stories About Older Women

Mary Sharratt on Moving Beyond Coming of Age

We live in a youth-obsessed culture. The cosmetic industry pushes wrinkle creams and hair dye on us while celebrities resort to fillers and surgery to preserve an illusion of eternal girlhood. Advancing age, once a mark of honor, has become a source of shame. Popular fiction, literary classics, television, and movies celebrate young heroines, from Elizabeth Bennett to Katniss Everdeen. But where are the stories about older women and why do we all need to hear them?

We live longer than ever before. Women’s lives don’t play out in one act, even though our culture programs us to think that way. It almost seems a travesty to imagine an older Elizabeth Bennett grown bored of Darcy and yearning to reinvent herself and embrace some new adventure.

Old-school male authors were really big on killing off their young heroines so they couldn’t even dream about maturing into women with agency. Shakespeare merrily committed femicide on Juliet, Ophelia, and Desdemona, to name just a few of his hapless heroines.

Why have so many authors, past and present, refused to let their heroines age? Why this reluctance to write about seasoned female protagonists who have been around the block more than once? Perhaps because too many people, even today, consider experienced women threatening. Since the time of witch burnings and scold’s bridles, male-dominated culture has been petrified of older woman who seize their power. That’s why stories about young women with a certain cut-off date are much cozier and less threatening.

But coming-of-age stories can only take us so far. We need to imagine lives beyond Act One, beyond a vague glimmering on the horizon. We need signposts to help us navigate our long and unavoidably complicated modern lives. We live in an age of divorce, blended families, and many of us pursue several careers and many paths of discovery over the course of a single lifetime. Contrary to cultural expectations, women do have exciting, juicy lives after forty and beyond. Contemporary fiction should explore and celebrate this.

Yes, there have been break-out books about older women—Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge, and even literary classics, such as Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway—but these are the exceptions that prove the rule. In the publishing marketplace, stories about older women remain a hard sell. Which is bitterly ironic, considering that most fiction is purchased by women over the age of forty.

Yet it’s not just an older audience that needs to read about older heroines. I would argue that girls and young women are in even greater need of literary role models to guide them way beyond a self-limiting Act One.

As a teenager, I was hungry for such stories. Some proof that I had something to look forward to beyond the awfulness of high school (not the best years of my life). Like Holden Caulfield, I was caught in a web of angsty adolescent nihilism which cast everyone from the cheerleaders to the teachers as a chorus of fakes and phonies. I needed a gutsy female role model to pull me out of this miasma.

Contrary to cultural expectations, women do have exciting, juicy lives after forty and beyond. Contemporary fiction should explore and celebrate this.

Eventually I found my heroine, not in the pages of a novel, but in Blackberry Winter, Margaret Mead’s memoir. I was electrified by this strong woman who didn’t give a fuck about preening for the male gaze and yet still had an amazing love life. Born in 1901, in an era when women were programmed for domesticity, she became a pioneering anthropologist and feminist icon. Her memoir, subtitled “My Early Years,” is not cut off at Act One, but only ends when she becomes a grandmother. Well into old age, Mead remained a mesmerizing and magnetic presence for being authentically herself.

Mead’s memoir is a rare jewel of female self-confidence in an ocean of women’s self-censorship and self-effacement. In Writing a Woman’s Life, Carolyn G. Heilbrun observes how both biographers and autobiographers have suppressed the truth about lived female experience to force it to conform to society’s script of how a woman’s life should be.

Heilbrun then discusses the Mother of All Female Memoirs, the first to appear in the English language. The Book of Margery Kempe (c. 1436–38) reveals the escapades of a woman mystic who wasn’t enclosed in a cell, but was literally all over the map. Kempe’s call to adventure unfolded amid the bitter disillusionment of midlife. She was forty, a desperate housewife, a failed business woman, a mother of fourteen children, and trapped in an abusive marriage. Marital rape was her lived reality—a fifteenth child might have killed her.

Her story completely exploded my every stereotype of medieval womanhood. Her life choices seem absolutely radical by the standards of our time as well as hers.

Since divorce was not an option, she seized back control by setting off on the perilous pilgrim’s path to Rome, Jerusalem, and Santiago de Compostela. She literally walked away from her unhappy marriage and blazed her trail across Europe and the Near East in an age when very few women traveled, even in the company of their husbands.

Alas, Kempe’s independence and eccentricities drew suspicion. When she returned to England, she found herself on trial for heresy. A guilty verdict would have seen her burned at the stake, yet she kept her spirits high by regaling the Archbishop of York with a parable of a defecating bear and a priest.

Most significantly, the spiritual mentor who stood by Kempe as she made her unorthodox choices was a woman in her seventies, the anchoress Julian of Norwich. Before leaving on her monumental pilgrimage, Kempe sought Julian’s counsel. This was an exceedingly vulnerable time in Kempe’s life. In leaving her husband and children, she had broken all the rules and was filled with self-doubt and uncertainty. Julian’s advice to trust her inner calling and not worry too much about what other people thought seemed to have a profoundly empowering impact on her. While Julian had chosen to wall herself into a cell and live as a religious recluse, she gave Kempe her blessing to wander the wide world.

if we look past the patriarchal smokescreen, we see that youth and aging are mirrors reflecting one another. The maiden and the witch are not enemies.

Kempe’s story would have been lost to history if she hadn’t recorded it in her autobiography, a tremendous act of foresight and courage that made her a literary pioneer. She dictated her story to a priest, who copied it down for her and whose ecclesiastical authority gave gravitas to her narrative.

We are hard-wired to frame our experience in stories. Almost anything we endure, no matter how painful, can take on a deeper meaning if we see it as one chapter in an overarching narrative. Stories give coherence and meaning to our often fragmented and chaotic lives.

Margery Kempe’s story proves that even in the Middle Ages, women had the power to re-invent themselves in midlife and beyond. If Act One disappoints, time to dive feet first into Act Two. We can continually re-vision our own narrative.

Our culture likes to pit women against each other. Divide and conquer. Popular tropes cast young women and older women as rivals or even enemies. In fairy tales a young maiden’s coming of age involves going out into the wild forest to encounter the scary old witch who acts as a foil to the maiden’s youth and innocence.

But if we look past the patriarchal smokescreen, we see that youth and aging are mirrors reflecting one another. The maiden and the witch are not enemies. The true coming of age unfolds when the maiden seeks out the witch who ultimately empowers her. Who teaches her to be fierce and not suffer fools.

As we mature, we are gifted with the superpower of seeing through the false scripts that consumer society hands us. We can see just how absurd it is to kill ourselves to emulate airbrushed fashion models. We understand that the greatest lover in the world can’t fulfill us until we are at peace with ourselves. And so we can let ourselves go, whatever our age. Paint the pictures we’ve always longed to paint. Learn French and travel the world. Dance under the stars and see visions. Offer our own song to the vast symphony of life.

We need stories that honor the entire sweep of womanhood, not just Act One. What would our literary canon and popular culture look like if it truly reflected the depths and breadth of our authentic, lived experience as women and girls today?

___________________________________________

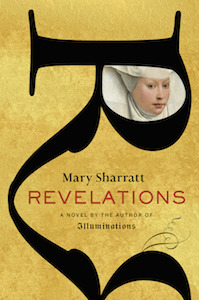

Mary Sharratt’s Revelations is available now via HMH Books.

Mary Sharratt

Mary Sharratt is on a mission to write strong women back into history. Her novels include Daughters of the Witching Hill, the Nautilus Award–winning Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen, The Dark Lady's Mask: A Novel of Shakespeare's Muse, and Ecstasy, about the life, loves, and music of Alma Mahler. Her latest novel, The Revelations, celebrates the adventures of her mature heroines Margery Kempe and Julian of Norwich. She is an American who lives in Lancashire, England. Visit her website: www.marysharratt.com