Leave Elena Ferrante Alone

David L. Ulin on the Baffling Impulse to Unmask a Beloved Writer

Claudio Gatti’s “Elena Ferrante: An Answer?” betrays its contradictions from the start. If we want an answer about Ferrante, after all, we only need to read her books. As most serious readers and writers recognize, it is not the creator who is important; it is the language, the sentences, the art. Ferrante, to be sure, is a famous recluse; the author of the Neapolitan Quartet, her name has long been known to be a pseudonym. In his investigation, however—published simultaneously on Sunday in Germany, France, Italy, and on the blog of the New York Review of Books—Gatti eschews literary theorizing, using real estate and financial records instead to argue that Ferrante is not who she appears to be.

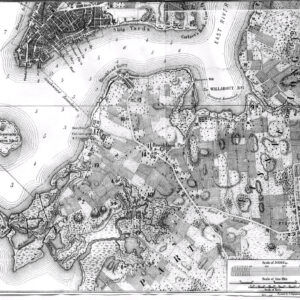

The first question to ask is why. Does anyone believe that knowing Ferrante’s secret identity will offer unexpected insights into her books? She’s not a superhero—or, for that matter, the presidential nominee of a major party who refuses to release his tax returns. And yet, I’m struck by Gatti’s assurance that money renders everything fair game, that we should treat a writer as we would a politician trying to avoid being found out. When did this become the way we think of literature? Does anyone care how much Ferrante earns or where she lives? Gatti follows a paper trail that begins with the purchase, in 2000, of “a seven-room apartment near Villa Torlonia, an expensive area of Rome,” and then, a year later, “a country home in Tuscany.” He tracks payments from her publisher, “obtained from an anonymous source.” Close your eyes and you can almost imagine he is writing about national security, that there is more than a writer’s privacy at stake.

Of course, in a world that treats politics as fiction (the Republican nominee is not a tax scofflaw, he’s a genius who won the first debate, or would have, had his microphone been working properly), it only makes sense that we’d wind up on the other side of the telescope. But as with much of the discourse in our culture, what’s most distressing about Gatti’s efforts is how beside the point they are. I don’t care about Ferrante’s real name, which is why I will not use it here—if, in fact, Gatti is correct. I don’t care what Thomas Pynchon looks like either, or whether J.D. Salinger left a pile of unpublished manuscripts behind. All of this is irrelevant to the work these writers have done, the way we know them, through their framing of the world, the stories and observations they share. Ferrante’s writing resonates not because of her name, or the property she owns, but because of who she is and how she translates that sensibility into language and narrative.

In part, I think, our fascination with the secret lives of writers has to do with the fact that we feel so close to them when we read. This is as it should be; reading and writing is exceedingly intimate. But that’s part of the trick of art, isn’t it?—that the artist is most fully themselves when in the process of working, that this is all we need to know? It’s why, as John Irving once suggested, the question of the autobiographical is irrelevant: “[A]n adult should … know,” he wrote, “that whether a novel is autobiographical or not is beside the point—unless the alleged adult is hopelessly inexperienced or totally innocent of the ways of fiction.”

This, I want to say, is also the case with Gatti, who mistakes (alleged) information for truth. He justifies his inquiry by quoting from a letter—soon to be published in the United States as part of a miscellany called Frantumaglia—in which Ferrante admits that “I don’t at all hate lies, in life I find them useful and I resort to them when necessary to shield my person, feelings, pressures.” For Gatti, “announcing that she would lie on occasion” means “Ferrante has in a way relinquished her right to disappear behind her books and let them live and grow while their author remained unknown.” But really, that’s just a lie of its own: at best, self-serving and at worst, a willful manipulation of Ferrante’s words.

What does it matter who Ferrante is? How does the question serve her—or us? I think of George Orwell (another pseudonym), who in 1936 published the essay “Shooting an Elephant,” about an incident in Burma, where as a colonial police officer, he killed a rogue elephant. “There’s no way of knowing,” George Packer writes in his introduction to Facing Unpleasant Facts, in which “Shooting an Elephant” appears, “whether the events in the essay ever happened. Orwell’s biographers haven’t been able to prove them either factual or false. … Would the essay be any less powerful if Orwell never actually shot an elephant? If you’re a literary sophisticate, the correct answer is obvious: of course not. All we have are Orwell’s words; they are what they are regardless of his life story, and only a naïve reader demands that they reflect the factual truth.”

A similar response applies to Ferrante—even moreso, since she has never claimed the mantle of essayist. Her work is fiction, so what difference does it make if she too is a creation, a construction, both on and off the page? “In an age in which fame and celebrity are desperately sought after,” Gatti argues, “the person behind Ferrante apparently didn’t want to be known. But her books’ sensational success made the search for her identity virtually inevitable.” Still, if this suggests some—or even all—of his motivation, it also tells us how little he understands about art and literature, and the subtle transference by which they work.

David L. Ulin

David L. Ulin is a contributing editor to Literary Hub. A 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, his books include Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles, shortlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay.