North American Coast, August – September 1786

White everywhere. Mist so thick it obliterates colors and edges. Up on the quarterdeck, our captain looks like an artist’s afterthought. He stands on the port side, gazing out toward the North American coastline. But it’s all one whiteness—sea, sky, and land. We can hear the flagship’s bell but cannot see her.

I climb partway up the steps and wait until he notices me.

“Monsieur Lavaux,” he says, inviting me up. When I reach him, I see his face, drawn and thin. François is right: the captain hasn’t been sleeping or eating.

Of course, all of us have lost sleep and weight since Alaska.

“How is your patient?” he says.

I shake my head. “It won’t be long.”

One year into the campaign, and I have but one patient. That’s never happened to me before. When I served under Admiral d’Orvilliers during the American War, the fleet lost almost a thousand men to dysentery and typhus. A thousand. In less than four months.

We’ve had no new sickness since leaving France. My current patient, a servant with one of our young lieutenants, was already ill when he joined the expedition. I still don’t know by what subterfuge the lieutenant managed to sneak him aboard. The servant will be our first death from disease. I might reasonably feel proud of this. But twenty-one men drowned three weeks ago—eleven from our ship, ten from the flagship. The calamity has made pride impossible.

“And the rest of the men?” the captain asks.

“Minor complaints—a sprained finger, one deeply lodged splinter, a few colds. Their spirits are still subdued, of course.”

The captain says nothing.

“Sir,” I finally venture. “May I offer you a sleeping draught?”

The captain turns to me, searches my face for a moment. “No, I thank you, Monsieur Lavaux,” he finally says. He turns back to studying the fog and its phantoms.

Below, I make my way to the cabin of our chaplain, Father Receveur. He’s waiting with François, who’s stooping awkwardly in a corner.

“Well?” the priest says.

“He looks exhausted,” I acknowledge. “But he refused my offer of a sleeping draught.”

The priest nods, unsurprised. “Look what else François brought,” he says, pointing to papers spread out over his cot.

He holds up a lantern for me as I look over the crumpled sheets, each containing just one or two lines of writing:

My Lord—

My Dear Lord—It is with great regret

My Dear Lord, it is with the greatest regret that I write to report

My Lord, it is with a heavy heart that I write to inform you of the death deaths death of your sons.

I draw back. “We shouldn’t be looking at this.” I turn to François. “Where did you get it?”

The boy tries to shrink back and hits his head on the shelf over the priest’s bed.

Father Receveur interjects. “It’s his job to sweep up the captain’s cabin,” he says. “These papers were strewn over the captain’s floor this morning.”

“Well, he obviously meant to discard them,” I say.

“He’s writing to the La Borde brothers’ father,” the priest says.

“I can see that.”

“The Marquis de la Borde—.”

“Yes.”

“—one of the richest, most powerful—.”

“I know who he is.”

“You know about the promise the captain made him?”

“I do.” I look back at the scraps. “A terrible letter to have to write. No wonder he hasn’t been sleeping.” I turn to François. “Has he finished it?”

The boy blushes before speaking. “He has some sealed letters on his desk,” he says. “I don’t know who they’re for.” He blushes again, and then I remember: The boy cannot read.

“What can we do?” I say.

“I don’t know,” the priest says.

It’s pleasing to hear the chaplain say for once that he does not know something.

In the morning I make my daily tour of the ship, greeting the men, looking and listening for signs of illness. On deck, I can’t help but regard the fog as a miasma that might infect us all. The officers murmur that we’ve advanced only sixteen leagues in three days and complain of the worthlessness of the Spanish charts on which they’re obliged to rely. Alas, I have no remedy for frustration. Mid-afternoon, a break in the mist allows them to get their bearings and observe the lay of the land as it spreads southward before us. But no sooner do we approach the shore then we’re surrounded again—clouds, rain, then a pallid, clinging mist in which we are becalmed for two days.

The only change is in my dying patient. He wakes in greater pain each morning, his breathing more labored, weeping to discover himself still alive. I administer laudanum—more and more each day—and try to ply him with spoonfuls of beef broth, which he ingests less and less of each day. He asks me to bleed him. In my experience, men who are bled die faster. Perhaps I should accede to his request.

The young lieutenant, his master, is busier now than ever, as he must make up for the loss of three officers in Alaska. But he spends a few hours each day by his servant’s side.

“I think he’s better today, Monsieur Lavaux,” he says, looking at me, eager for confirmation.

His servant lies insensible on the pallet, his feverish skin looking more like rain-beaded marble than the sheath of a living man. But I don’t disabuse the young lieutenant of his hope.

François is waiting for me outside of my cabin. “He’s still not sleeping or eating,” he says.

“Who?”

“The captain,” he says, eyebrows raised in impatience. “And I found more of these.” He offers me a fistful of wastepaper.

I uncrumple one. An ashy bootprint over the handwriting:

Please understand, My Lord, there was no wind that morning, nor a cloud in the sky. The water of the bay was like glass.

“You shouldn’t be showing these to anyone, François.”

“I’m not showing them to ‘anyone,’” he cries. “I’m showing them to you.” He bows his head, surprised and embarrassed by his own vehemence.

“What can I do?” I say.

He bites his lower lip. “I was wondering.” He clears his throat. “Could you give me the sleeping draught—just a little—and—and—I could put a few drops in his water at night.”

I stare at the boy, horrified and amused and impressed.

“He always drinks water at night,” he adds.

When he leaves, he ducks his head to clear the doorway. He’s grown tall in the year since we left France. Someone needs to teach him how to shave.

At last, a clear day with light, variable winds. I watch our captain and the young lieutenant work together to determine the sun’s altitude then check the ship’s chronometers. Father Receveur, who imagines himself a savant, joins them, but he spends more time looking at the captain than at the sky. Another officer is occupied draughting the contours and visible high points on land. The sailors take advantage of the sun to clean: Some swab the decks while others do laundry. Clothes flutter from the lines like comic signal flags. The flagship is in hailing distance off the starboard bow. Her outlines are so clear now it’s hard to imagine we couldn’t see her this time yesterday.

Father Receveur joins me on deck.

“How is he?” I say.

He nods. “Fine, I think,” he says. “Everyone looks happier today. Even the animals.” He indicates the three sheep we have left from our time in Chile.

“Spoken like a true Franciscan.”

He spreads his arms out before himself. “As you see,” he says, then adds: “I wonder if people recover from grief more quickly in warmer climes.”

“I was wondering the same.” In fact, I’d been enumerating in my mind the needed elements: light, warmth, visibility, colors.

“Our captain looks better rested too.”

“Mm. Yes,” I say. I do not confess to him my arrangement with François.

Just before nightfall, a strong wind from the west-northwest pushes before it a wall of white that overtakes the ships in minutes. We also encounter strong cross-currents suggestive of a nearby bay. I’ve sailed enough to know the risks: we may be driven ashore and run aground, or driven into a gulf and embayed. As expected, a hail from the flagship and a command shouted across to veer back out to sea. Before long we are pitching about in the relative safety of the open ocean.

The servant dies during the night. In the morning, I wake the young lieutenant, who cries out when I tell him. He’d still believed the man might recover. I used to believe that people suffered more over sudden, unexpected deaths than over long, protracted ones, but I no longer think so. Grief always lands heavily when it falls.

I make my way to the captain’s cabin. He calls “Come in!,” but his face falls when he sees me. “Is he dead?” he asks.

I ask when we might expect to make landfall for a burial. Not for a month, he tells me. Not till we reach Monterey. He absently places a hand on what looks like a stack of correspondence.

“I’m afraid it means another condolence letter, sir.”

He takes his hand back and looks up at me, eyes narrowed. “Not at all,” he says. “This man was not my responsibility.” It’s the young lieutenant, he says, who has the difficult letter to write.

“Of course,” I say. We should bury the man at sea, I tell him. This practice, common in French ships, of keeping corpses on board till they can be buried on land, is repugnant and insalubrious.

He agrees, then instructs one of his officers to find a carpenter and sailmaker to help the young lieutenant prepare his servant’s body. An hour later the captain arrives on deck, hails the flagship through the mist to report that we’ve had a death on board, then summons all hands for the service. Father Receveur has the perfect, sonorous voice for the office. The fog renders everything and everyone less corporeal; it’s as if the priest were consigning us all to the deep. But it’s the servant’s body that’s dropped overboard. He vanishes before we hear the splash, the mist swallowing him whole before he hits the water. The captain runs a hand roughly across his face as he turns from the burial of the man who was not his responsibility.

For the first time in my long career as a naval surgeon, I am without patients.

François finds me again. “He’s still at it,” he says, clutching more pages.

My Lord, I hardly need tell you of your sons’ superior qualities as officers. Had they been spared, they would have had brilliant careers.

Indeed, I begin to wonder how I can come home when they cannot.

“I need more laudanum,” François says.

“Shh!” I command. Our cabins’ walls may be made of thick planks, but there are gaps. I fix the boy with what I hope is a hard stare. “You’re not using it yourself, are you?”

He shakes his head, eyes wide with surprise and insult.

“Is he eating?”

“Mostly broth and bread.”

“His cook should—.”

“It’s what he asks for, Monsieur Lavaux.”

Laudanum and broth. The consumptive servant’s last diet.

“You have to do something, Monsieur Lavaux,” the boy says. “He’s going to die.”

“Nonsense,” I say sharply. “The captain is in perfect health.”

But I see no sign of the captain for several days. The officers don’t say anything in my hearing about it, but I sense among them an underlying anxiety.

For a week, we alternate between white calms and white gales.

Then, a clearing. The crew pours onto the deck, starved for sunlight. We can see for leagues in every direction. Great snowbound peaks in the eastern distance. Lush green islands dotting the coastline. A bay open before us, too deep to see to the other end. The officers note its position, but we sail on without exploring it, our orders to reach Monterey before mid-September. Father Receveur joins me again at the rail.

“Perhaps that was the Northwest Passage,” I say as the opening recedes from view.

“There is no Northwest Passage,” he declares.

“You know this for a fact.”

“Not for a fact—not a geographical fact, at least,” he says. He avidly scans the wide view before us as if to make up for the days when there was nothing to see. “I suspect this continent was not created for the convenience of European commerce,” he says. “There’s no easy way here—no short cuts.” He breaks his outward gaze and looks over at me with a grin. When he smiles one can see the youth that’s usually hidden under his cassock and behind that clerical certainty.

“Father,” I say suddenly, startling him. “What if we wrote that letter for the captain?”

He turns to me. No longer smiling. “You cannot be serious.”

We retreat to the privacy of his cabin.

My Lord, it is with the most painful regret that I inform you of the loss of your sons in a tragic and unforeseeable accident in Alaska on July 11, 1786.

I have asked that the official report from the flagship be forwarded to you so you may see for yourself the precautions we took. Not one of us had any presentiment of danger.

“Too defensive,” I say.

“He has to assure the marquis that he didn’t wantonly throw his sons into danger.”

“Too late for that.”

I hope it may be of some consolation to know that your sons were lost while heroically, though unwisely, trying to aid another boat in distress. Sadly, both boats and all 21 men aboard were lost in the violence of the currents in which they were caught.

“Is that actually consoling?” the priest says.

“I don’t know. Is it?”

The moment we learned of the accident, Monsieur de Lapérouse and I ordered search parties to find and help survivors. Indeed, I myself directed one such party in the area of the bay where the boats were lost. Alas, we found no one, not even one body, despite many hours spent searching in the days following the tragedy.

“Now that is defensive.”

“Can it be helped?”

We were obliged to delay our departure as a result…

“Obliged?” I say.

“What’s wrong with ‘obliged’?”

“It sounds as if we begrudged the time spent looking for the lost men.”

Indeed, we delayed our departure by two weeks in the vain hope that someone would turn up alive or that we would find at least one body to properly mourn and bury.

“That’s better.”

Neither of us wants to write out the final copy, but I prevail. “You know medical men can’t write anything decipherable,” I say. He agrees to play scribe if I agree to find a way to deliver the letter.

I find François in the galley, drinking with the captain’s personal cook. “You do realize that if you turn this boy into a drunkard, there will be less for you to imbibe, Monsieur Deveau?” I say as I draw François away. I take him up on deck, where the fog has enfolded us again, curling around the masts and sails and men like tentacles. “Don’t give it to him directly,” I say, handing the letter to François. “Just place it discreetly on his writing table.” The boy wanders off unevenly. After he disappears into the mist, I look up and watch while thin, wet ribbons of cloud rush overhead, distorting the light of the quarter moon.

Dead calm the next day. Mid-morning, I’m alphabetizing my collections of remedies and liniments when I hear a commotion outside the infirmary. I open the door to the young lieutenant holding up a bloodied and dazed François.

“What in God’s name?” I cry.

“He did something to greatly displease the captain,” the lieutenant says.

“The captain?” The captain has never struck a crewmember before.

The lieutenant shrugs unhappily. He looks at François with such angry bewilderment I’m afraid the boy may sustain more blows.

“Go get Father Receveur,” I tell the lieutenant, then take the boy into the infirmary. “What did you do, François?”

“What did you do?” the boy shouts back.

He is a mess of tears and snot and sweat, but the physical injuries are relatively minor: a small contusion on the back of his head, some bruises and lacerations on his arms and legs.

Father Receveur rushes in. “My dear boy, what happened?”

François regards us both with aggrieved belligerence. “He held up your paper and kept shouting, ‘Who did this?’ ‘Who did you talk to?’”

The priest and I look at each other. The priest’s usual confidence drains out of his face along with all of its color.

“What did you tell him?” I ask François.

“You’d like to know, wouldn’t you?” He juts out his chin then grimaces in pain.

“Yes, we would very much like to know.”

The boy sneers at us and at our patrician fear. “I didn’t say anything,” he says. “Pretended I didn’t know what he was talking about. That’s when he shoved me into the wall.”

“You could have offered us up, my boy,” the priest says. I roll my eyes. Ex post facto declarations of selflessness: so typical of the religious.

“Could have,” the boy says. “But didn’t. Anyway, he’s finished the letters. He put his paper and quills and inkpots away.”

The priest and I exchange glances again. So it might have worked, our raised eyebrows seem to say. We don’t know, of course. Maybe he sealed up our letter and added it to his stack. Maybe he copied out our words in his own hand. Maybe the fact that someone on board felt compelled to compose it for him spurred him to complete his own letter. Or maybe the new letter isn’t to the Marquis de la Borde at all but to someone else—the Minister of Marine, perhaps—complaining of interfering crewmembers, asking that François’s pay be cut—or requesting that his chaplain and surgeon be transferred from the ship at the next port of call.

I clean the boy up and send him to his berth for the day.

“We should teach that boy to read,” Father Receveur says. “He might make something of himself.”

I knock on the captain’s door, dread knotting up my insides. But when I see him, I realize his dread has been worse than mine. His face is pale with misery. “Is he all right?” he says.

“He’ll be fine,” I say. “But if he could be relieved of duty today—.”

“Of course.”

“Is there anything I can do for you, sir?” I ask.

He shakes his head at first, then says,“A few weeks ago you offered me a sleeping draught—.”

“I’d be happy to help with that, sir.”

“Thank you, Monsieur Lavaux.”

“Sir—.”

He looks up, wary and ashamed, but I can see that his anger is not yet spent.

“He’s very devoted to you, you know.” It’s not what I meant to say.

The captain blinks hard as he waves me away.

I go back out on deck. I’m needed below—a short-lived but quite unpleasant stomach ailment seems to have broken out among the marines. But first I stand gazing out into the blankness around me. I look down over the rail and am surprised to find dark shapes below—seabirds of some kind. From their postures I can tell they’re sitting on the surface of the water. But the water on which they bob remains invisible, overlaid with mist and opaque to the sky. The birds seem to float, unmoored, in mid-air, like magical creatures who have learned how to hold themselves in suspension.

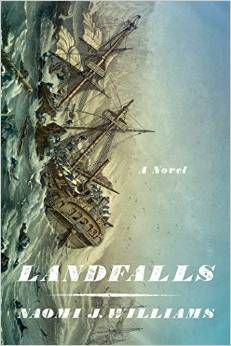

From LANDFALLS. Reprinted by arrangement with Aragi Inc., to be published by Farrar Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2015 by Naomi Williams.