Jonathan Lethem on the Lost Conversations of Ross Macdonald

Getting Inside the Head of a 20th-Century Literary Master

How I came to edit the book that became It’s All One Case: The Illustrated Ross Macdonald Archives (published this month by Fantagraphics) is a story that actually began 46 years ago, in the winter of 1970, when freelance New York music journalist Paul Nelson placed a long-distance phone call to Kenneth Millar in Santa Barbara, California. Nelson helped invent rock criticism and went on to become a legendary writer and editor at Rolling Stone. Millar, at that point the author of 21 novels, was better known as Ross Macdonald and had created arguably the third most famous fictional private eye in literary history: Lew Archer. Following in the same gumshoed footsteps as Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade and Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, Archer shared the same Southern California climes as his predecessors—but his was a new kind of hard-boiled. Infused with Millar’s encyclopedic knowledge of romanticism and symbolism—and nearly a year in therapy—Archer looked for different types of clues, solved his cases with a different kind of understanding.

Nelson had read almost all of Millar’s books, but he wasn’t reaching out as a fan when he obtained Millar’s phone number from Santa Barbara information. Personal problems prevailed and, in his own words, he was “Close to explosion . . . I guess I felt like somebody in one of Millar’s novels—those books to which, with hope, I clung—and badly needed a share of the understanding and compassion he’d shown his characters.”

Regardless of the reason, the connection had been made. Years later, Nelson spent much of the summer of 1976 in Santa Barbara interviewing Millar for a feature story in Rolling Stone. By then, the mystery novelist was at the height of his career. He had just published his 24th (and though neither men knew it, his last) book. Each new novel was anticipated by an eager international readership; public and critical acclaim walked hand in hand. Millar was hugely responsible for detective fiction finally being taken seriously.

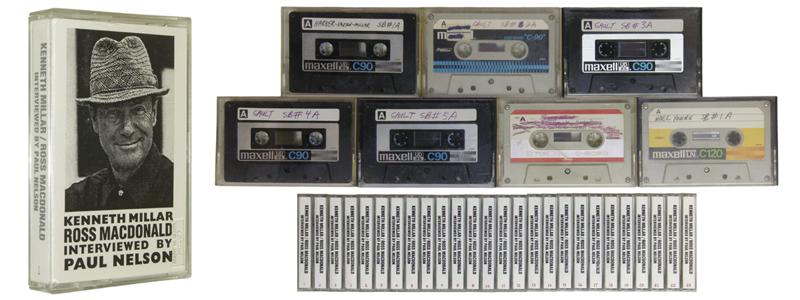

Alas, for reasons as simple as writer’s block or as complicated as one man honoring another man’s secret, the magazine article was never written. Seven years later, Millar died from Alzheimer’s. In the years that followed, Nelson tried to pitch a book based on the interview tapes (somewhere between 39 and 47 hours’ worth), but to no avail. In 1991, Nelson, in need of money, sold the recordings to the Millar archives at the University of California, Irvine.

Slow dissolve to 2010 when, in the midst of reading the manuscript of my first book, Everything Is an Afterthought: The Life and Writings of Paul Nelson, Fantagraphics publisher Gary Groth shot me an email late one night: “HOLY SHIT! Did I read your ms right, that Nelson has many many hours of interviews with Ross Macdonald squirreled away somewhere?” Indeed, Nelson had shared copies of his recordings with his friend Jeff Wong, an illustrator and Ross Macdonald scholar who maintained one of the world’s largest private archives of Macdonald collectibles. In the course of researching my book on Nelson, Wong, who also eventually came onboard as the book’s designer, had in turn provided me with copies of the tapes. “If so,” Groth concluded in his email, “what are we waiting for? Let’s publish ’em.” His logic seemed sound, and I agreed to do the book.

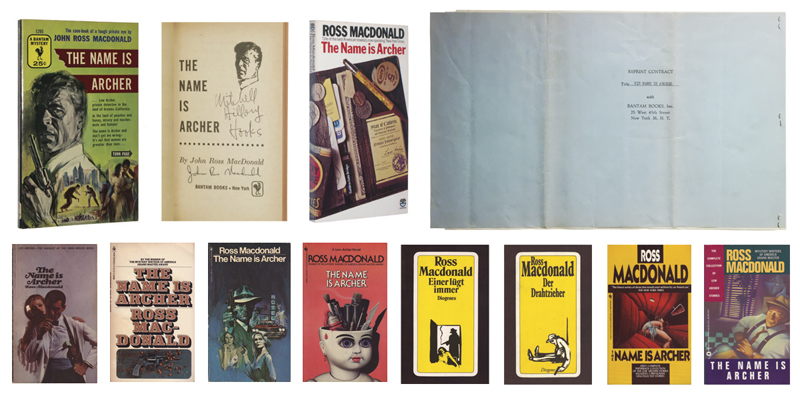

In the midst of my transcribing the interviews, then editing and shaping them into what became It’s All One Case, Wong proposed to Groth and myself that we “illustrate” the interviews with visuals from his collection—including full-color reproductions of the covers of the various editions of Millar’s books from around the world, magazine spreads, and reproductions of pages from his manuscripts and letters. Groth and I agreed. Photographs (many of them never before published) from outside sources also found their way into the book, including those by celebrated photojournalist Jill Krementz. The finished volume boasts over 1,300 images that bring new dimensions to Millar’s words. A fitting tribute to a writer who would have turned 100 last year.

Nelson is gone now, too. Thirty years after his trip to California to interview Millar, he died in 2006 at the age of 70 with memory problems of his own—alone in his apartment with a copy of Tom Nolan’s Ross Macdonald: A Biography at his bedside.

Nelson left behind many friends and admirers. One of them, New York Times bestselling writer Jonathan Lethem, kindly offered to discuss his old friend, who introduced him to the writings of Ross Macdonald. Lethem is the author of nine novels, including The Fortress of Solitude and Motherless Brooklyn. His new novel, A Gambler’s Anatomy, is also being published this month, by Penguin Random House.

Kevin Avery: When we first spoke back in 2006, you told me that Paul, who was your good friend, led you to Ross Macdonald, “who became a writer that mattered to me.” What is it about Millar and his work that matters to you?

Jonathan Lethem: Well, the first and simplest thing to say is that I fall in with the critical assessment that Macdonald is Hammett and Chandler’s equal, and that he furthers and deepens their fundamental accomplishment, of securing the “classical California hard-boiled first-person detective” as a branch of American letters, even if it’s a peculiarly specific one. I think the idea that he was as important as his two predecessors floated around for a decade or so, when he was getting reviewed on the front page of the Times Book Review, and then it faded again. I hope this recent surge of interest helps restore it.

For better or worse, I don’t think anyone’s really come along who comes near since. No one who extends that style into a significant body of work, though there are individual books of great interest that operate in that mode: Crumley’s The Last Good Kiss being an extremely fine example. I actually think James Ellroy could have been the one to do it, if he’d burrowed into the style of Brown’s Requiem and gone further. But he had other priorities, which I don’t begrudge him.

I’m speaking here of a really particular set of motifs and iconographies, not “crime writing” or “the mystery” in a general sense. There’s astounding work done by Richard Stark, Charles Willeford, Jerome Charyn, Mark Smith, and loads of others since Macdonald’s heyday. But not in this precise area. Maybe it’s so specific that it can only subsequently be watered-down, or satirized, or turned into a reliable brand, the way Robert Parker’s very solid and readable Spenser novels did. You could read perfectly fine hard-boiled detective novels for the rest of your life, but it may be that Macdonald was the end-point for using it as a persistent and sustained way of scrutinizing American life, and his own soul, as he did.

The change he turned on Chandler’s method is very striking to me. He leached it of a certain hysteria and romanticism, cooled it somewhat, and made it as precise as a sonnet or ode. Or perhaps I mean as a code. It seems to be precise and objective but it also seems to stand in for something unspoken and deep, and vastly irrational and mythic just beneath that cool surface. It seems to become a sort of rehearsal for uncovering American trauma. The extremely compressed time sequence of the detective’s operation, and yet the long decades of denial and distress and buried remorse that are being examined, each time out—it’s a very formal and even baroque narrative machine. It has nothing to do with any kind of outward “realism,” though it doesn’t seem to exactly violate plausibility. I really do think it’s as precise as a sonnet. I relied on it enormously in both of my two hard-boiled detective stories, eccentric or flighty as they might seem on the surface. It also formed the narrative model for the entire second half of The Fortress of Solitude.

From the exclusive interview with Millar featured in the Italian edition of The Goodbye Look published in Il GialloMondadori #1114 (1970)*

From the exclusive interview with Millar featured in the Italian edition of The Goodbye Look published in Il GialloMondadori #1114 (1970)*

KA: As writers, are there any similarities between Paul and Ken?

JL: Oh, god, I don’t even know how to begin. You know much better than I do, at this point, having spent time actually listening to these tapes. The superficial psycho-biographical resonance is of course irresistible—the lost or abandoned children, the reverent but somehow crushed relationship to the love of the women in their life.

I knew Paul, and I didn’t know Ken Millar, so I’m hesitant to project these intuitions much further, but the transcribed conversation is heartbreaking for the sense that Paul is fitting himself into the skin of a man who’d given Paul a lifeline in the form of his work—yet Paul can never say this directly, and Macdonald can only inch along in his reserved, scrupulous way, making sense of the reserved and scrupulous attention Paul was giving to his every word. In both men there’s a powerful sense of something I’d call a “displaced romanticism”—one that could never look at its object directly, for fear of distortion, or exaggeration, or falsification. The reward is in this area of precision and intellect, the sense that everything mattered and needed to be measured and described very precisely. The cost is in a devastating loneliness, a sense of disconnection and lapsed promise—nothing ever embraced on the spot, for what it was.

KA: In the interviews, Millar repeatedly de-emphasized the importance of Lew Archer, the fictional private eye who narrated 18 of his 24 books and a handful of short stories. He claimed that “Archer could be taken out of the books and it wouldn’t actually change them terribly in their structure or their meaning.” Paul remained unconvinced. He saw Archer as “an honest, compassionate, and understanding father figure,” and as such was one of the main reasons for reading the books. What do you think? Is the character of Lew Archer, and how he viewed the goings-on in the books, as dispensable as Millar seemed to believe?

JL: It’s such a strange proposition, hard to credit. Paul was right to be skeptical. How would the books operate at all without Archer? It would be like removing the skeleton from a body. He’s the roving consciousness, a kind of convergence of a literary character and a principle of omniscient narration. Of course he’s also a wish-fulfillment figure of competence, reconciliation, sanity, and endurance, and so Millar may have been identifying him as the only form of indulgence he’d allowed himself in an otherwise rather flayed vision of humanity. The nearest I can come to a useful thought-experiment for picturing the Archer books without Archer is to think of the difference between Simenon’s Maigret books and those he wrote that feature only the criminals and victims, the families and bystanders. In every respect they’re very much like Maigret books without the detective’s salvific and abiding presence. I used to think those were the more “serious” books, and I gather that was Simenon’s belief, but in some ways I’ve come to wonder if there isn’t a higher seriousness in also engaging our desire for a witnessing conscience, while turning such a remorseless eye on the workings of so-called civilized human beings.

KA: As indebted as he was to Hammett and Chandler and the fictional detective tradition they created, Millar cited F. Scott Fitzgerald as his favorite writer and The Great Gatsby as his favorite book. Do you think this is reflected in his own work and, if so, how?

JL: It’s probably impossible from this distance to credit the spell Fitzgerald and Gatsby cast over American writers of a certain generation, and perhaps particularly the hard-boiled writers, even if it was in the form of an apparent refutation. I know that Fitzgerald was also the favorite of Cornell Woolrich, who wrote several early novels in a Fitzgerald “jazz age” style before turning to the doomed paranoiac crime stories that were his signature. The key is probably to think of “romanticism”—which, even when exposed as being laden with innate disappointment or prone to fakery, as is already the case in Gatsby, is still romanticism. A similar relationship exists in the hard-boiled writers, who require an undertow of romanticism to pile their disappointment or cynicism on top of—like a principle of underpainting. Of course there’s also Hemingway, who may be the harder debt for Hammett himself, and, later, Macdonald to acknowledge precisely because they owe him even more than they do Fitzgerald—but also because Hemingway’s career went on from triumph to triumph (up to a point), even as they were coming of age as published writers, so they’re not looking back on a lost and tragic figure, but rather up at a rather boorish celebrity who’s taking up a tremendous amount of public oxygen. You might almost say that the hard-boiled novelists split the difference, stylistically, between Fitzgerald and Hemingway.

For an American writer of a certain age and temperament to point to Fitzgerald as their favorite is probably a bit like wearing their heart on their sleeve; a way of saying, “I was young once too, you know!”

From a previously unpublished Ross Macdonald Essay called “The Freelance Writer in Today’s World” (1973)†

From a previously unpublished Ross Macdonald Essay called “The Freelance Writer in Today’s World” (1973)†

KA: You and Paul Nelson became friends around 1983, and he became something of a mentor to you, reading your early stories as well as parts, if not all, of Gun, with Occasional Music. The summer of that same year, Ken Millar died. Not only did Paul finally write about his hero in Rolling Stone, penning his obituary, he also shopped around an idea for a book, based on the 1976 interview tapes, called Ross Macdonald: An Oral Biography. But it never got past the book proposal stage.

Did Paul share any of this with you? That he’d spent weeks with Millar in California, amassing dozens of hours of tapes? When he spoke of Ross Macdonald, was it ever in the sense that he was more than just a writer whose books he’d read?

JL: We first met in ’83, yes, but I don’t remember talking with him about Macdonald at that point, so I can’t conjure up any sense of his immediate response to Millar’s death. In fact, when we first talked—it may be worth emphasizing here that I was nineteen years old—our points of contact were much more to do with Bob Dylan, the New York Dolls, and Philip K. Dick, who Paul had only just discovered, and on the subject of whom I was in the rare position to play the expert. Paul might not have known, initially, that I’d read all of Hammett and Chandler already. But I hadn’t yet read Macdonald—I didn’t, until Paul insisted, and then I became a huge enthusiast in a very short time. But by that time I was in California, almost two years later, and beginning to puzzle together what would become Gun, With Occasional Music.

The book of mine Paul really read and helped with was the novel that preceded Gun, which was and will always remain unpublished. That was heroically generous of him, since the book was truly bad. But it was bad in a fake-Philip-K.-Dick way, so he could at least see what I was getting at.

Paul’s Macdonald tapes were certainly a subject of fascination when I did learn about them, but I think the thwarted book project was already a subject of remorse and avoidance in the years after, when Paul made me something of a sounding board for his writing difficulties. The book he was intent on getting a contract for at that point was his Chet Baker biography. Obviously something not destined to happen, and impossible to fulfill retroactively, as you’ve done here to such remarkable effect with the Macdonald.

The extraordinary extent of his identification with Millar, and the intimacy and richness of those conversations, was something I only discovered on reading your book. That was Paul for you: a monomaniac, a house with many rooms, all of them firmly partitioned. I was lucky enough to get to rummage around in the Orson Welles room, and the Bob Dylan room, and the Howard Hawks. I didn’t have that same luck with Millar/Macdonald, despite Paul’s being the cause of my own interest in him. Fortunately enough, that room is the one you’ve opened up by editing the tapes. So I’m lucky all over again. How I wish Paul were here to be part of it all.

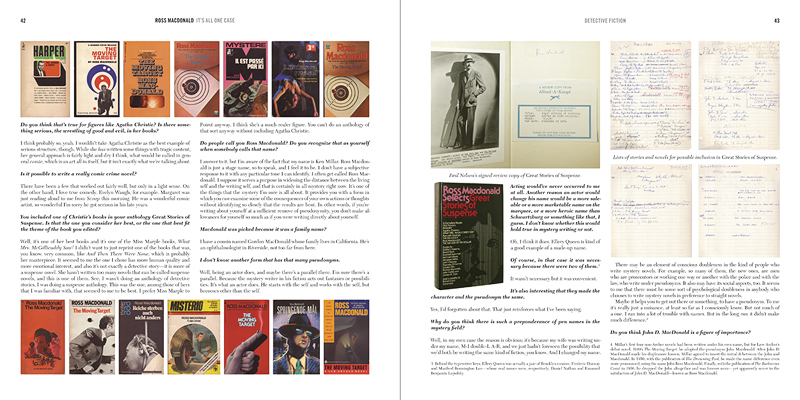

A Spread from It’s All One Case: The Illustrated Ross Macdonald Archives featuring Paul Nelson’s copy of the Macdonald edited anthology Great Stories of Suspense from 1974

A Spread from It’s All One Case: The Illustrated Ross Macdonald Archives featuring Paul Nelson’s copy of the Macdonald edited anthology Great Stories of Suspense from 1974

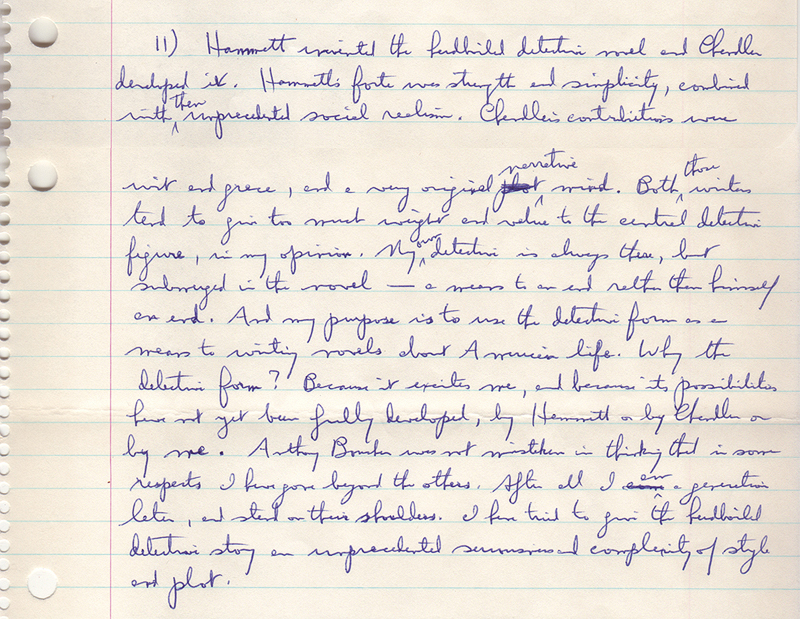

* Transcription: “Hammett invented the hardboiled detective novel and Chandler developed it. Hammett’s forte was strength and simplicity, combined with then unprecedented social realism. Chandler’s contributions were wit and grace, and a very original narrative mind. Both those writers tend to give too much weight and value to the central detective figure, in my opinion. My own detective is always there, but submerged in the novel—a means to an end rather than himself an end. And my purpose is to use the detective form as a means to writing novels about American life. Why the detective form? Because it excites me, and because its possibilities have not yet been fully developed, by Hammett or by Chandler or by me. Anthony Boucher was not mistaken in thinking that in some respects I have gone beyond the others. After all I am a generation later, and stand on their shoulders. I have tried to give the hardboiled detective story an unprecedented seriousness and complexity of style and plot.”

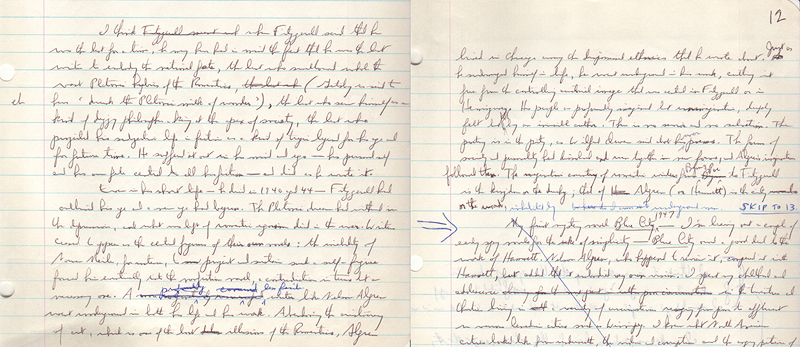

† Transcription: “I think when Fitzgerald said that he was the last for a time, he may have had in mind the fact that he was the last writer to embody the national fate, the last who swallowed whole the vast Platonic hybris of the Romantics, (Gatsby is said to have ‘drunk the Platonic milk of wonder’), the last who saw himself as a kind of dizzy philosopher-king at the apex of society, the last who projected his subjective life in fiction as a kind of tragic legend for his age and for future time. He suffered it out in his mind and ego—his personal self and his own fate central to all his fiction—and died as he wrote it.

Even in his short life—he died in 1940 aged 44—Fitzgerald had outlived his age and a new age had begun. The Platonic dream had withered in the depression, and what was left of romantic egoism died in the war. Writers ceased to appear as central figures of their own novels: the inability of Norman Mailer, for instance, to project and sustain such a self-figure forced him eventually into the nonfiction novel, a contradiction in terms but a necessary one. A less facile writer like Nelson Algren went underground in both his life and his work. Abandoning the aristocracy of art, which is one of the lost illusions of the Romantics, Algren lived in Chicago among the dispossessed ethnics that he wrote about. Just as he submerged himself in life, he went underground in his work, cutting it free from the controlling auctorial image that was central in Fitzgerald or in Hemingway. His people are profoundly imagined but unimaginative, deeply felt but felt by an invisible author. There is no savior and no salvation. The poetry is in the pity, as Wilfred Owen said about his war poems. The forms of society and personality had dissolved and run together in new forms, and Algren’s imagination followed them. The imaginative country of romantic writers from Byron & Poe to Fitzgerald is the kingdom or the duchy; that of Algren (or Hammett) is the city or the ward, inhabited by underground men.”

Kevin Avery

Kevin Avery's writing has appeared in Mississippi Review, Penthouse, Weber Studies, and Salt Lake Magazine. His first two books, Everything Is an Afterthought: The Life and Writings of Paul Nelson and Conversations with Clint: Paul Nelson's Lost Interviews with Clint Eastwood were being published in the fall of 2011 by, respectively, Fantagraphics Books and Continuum Books.