Jane Austen’s Emma Was Basically Torn Apart in Workshop

On the Early Reception of a Classic Novel, on Both Sides of the Atlantic

Biographies of books are typically created for publications of great historical importance: Copernicus’ De revolutionibus, for example, or Shakespeare’s First Folio. As a humble, unremarkable American reprint, the 1816 Philadelphia Emma is an unusual candidate for such an exploration. To recover the missing history of Austen’s earliest American readers, however, there is no better way than to pursue the traces they left in the books they read.

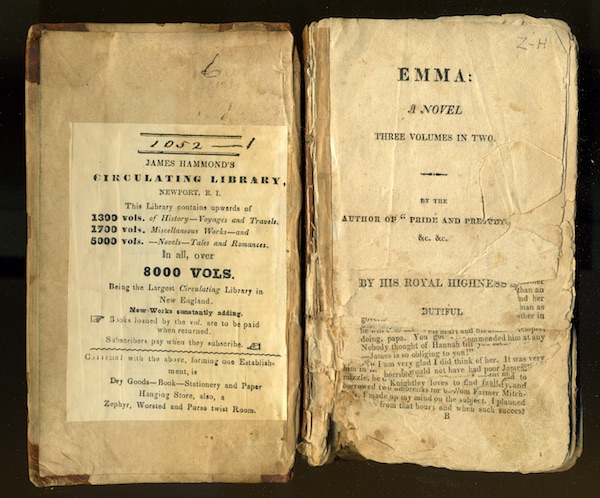

For comments on the experience of reading Emma, we must look to the most astonishing survivor among the six remaining copies of the 1816 Philadelphia edition: the one now held by the New York Society Library, a private membership library founded in 1754. These volumes’ level of disintegration is well conveyed by David J. Gilson’s description of them in A Bibliography of Jane Austen: “spines decayed and broken, pages much worn and decayed throughout, parts of many pages missing.” The title page, dedication, and first several pages of volume one are all in tatters. As a bookplate on the inside front cover makes clear, this copy was formerly owned by James Hammond’s Circulating Library in Newport, Rhode Island, which touted itself as “the Largest Circulating Library in New England,” with “over 8,000 volumes,” the great majority of which—5,000—fell into the category of “Novels—Tales and Romances.” Thanks to a trustee, the New York Society Library acquired 1,850 volumes from the Hammond Library in 1868, among them this annotated Emma. The sheer physical deterioration of this copy indicates that its volumes, still in the original publishers’ boards, were not up to the rigors of library members’ use. The exact year or years in which the annotations were added is unknown.

Careful though Gilson was to account for the external physical condition of this copy, he made no mention in his Bibliography of the historically valuable marginalia penciled by anonymous readers into the second volume. These responses first came to public view in 2015, as part of an exhibit titled “Readers Make Their Mark: Annotated Books at the New York Society Library.” In an accompanying blog post about the 1816 Philadelphia Emma, exhibit co-curator Madeline McMahon highlighted the importance of comments “by an ordinary reader, for a book about ordinary life.”

McMahon attributes all the marginalia to a single reader, whom she guesses is female, based on the handwriting. To my eye, however, two distinct hands are visible, neither obviously belonging to a man or a woman. One writer pressed firmly with the pencil, wrote in a formal cursive, and inserted only a few responses; the other scrawled thoughts with light pressure on the pencil and commented frequently. Some of the annotations, especially by the latter, are very faint and require significant deciphering; here, too, my guesses differ from McMahon’s. Both readers responded strongly to particular moments in volume two and also recorded summary judgments on the final page.

The reader with the more formal handwriting focused throughout on the novel’s heroine. At the bottom of the page on which Emma “smiled her acceptance” of Frank Churchill’s agreeing to join the Box Hill expedition, this reader wrote, “Highty tighty” (a variant of hoity toity). At the bottom of the page on which Mr. Knightley and Emma agree that they are not “really so much brother and sister as to make it at all improper” to dance together, this reader wrote—sagely, though with different spelling than Austen’s—“I expect Emma is going to marry Mr. Knightly.” On the last page of the novel, directly over the printed word “finis,” this reader wrote “I am delighted to get through with Emma Woodhouse or Mrs Knightly.”

Even more critical was the other reader, who alternated between global comments on the novel and responses to individual characters. An almost completely illegible comment on the inside flyleaf of the second volume is headed “Silly Book,” and that sentiment pervades this reader’s responses. Following Frank Churchill’s invitation of Emma to dance, this reader recorded the following judgment: “This book is not worth reading whoever the author, as their time had better been spent in reading than inventing. By one who has read this.” A similar, though more concise, thought—“I wonder who likes this book”—appears at the top of the page on which Mrs. Elton declares that “without music, life would be a blank to me.”

This reader’s especial dislike of Mrs. Elton is evident in two further annotations. “How disagreeable Mrs Elton is” appears at the top of the page opposite Mrs. Elton’s declaration, apropos of the strawberry-picking expedition to Donwell Abbey, “I wish we had a donkey.” Similarly, “Mrs Elton is a goose” is the judgment recorded after Mrs. Elton states, at Box Hill, “I do not pretend to be a wit.” In contrast, this reader made only one comment on Emma: at the end of the page on which “Emma doubted their [her guests] getting on very well,” this reader remarked, “Emma is always doubting.” On the final page, rotated clockwise, appears this reader’s greatest gift to reception history, in the form of summary judgments of Austen’s characters, laid out in a chart:

Mr. Knightley_____tolerable

Emma_____________intolerable

Harriet____________very pleasant

Frank_____________delightful

Jane______________enchanting

Woodhouse_______grouty

Miss Bates________Full of Gab

El[ton]____________d—d sneak

[Mrs. Elton?]______vulgar woman

The very unusual word “grouty” confirms beyond any doubt that these adjectives were chosen by an American reader. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this word (meaning “sulky, cross, ill- tempered”) exists only in a few instances of 19th-century usage, all from the United States. “D—d,” of course, is an abbreviation for “damned”—so Mr. Elton, in the eyes of this reviewer, was a “damned sneak.” The name below that of Elton, while so faint as to be illegible, must logically be that of his certainly “vulgar” wife.

Both this concluding list and the marginal annotations invite comparisons to the “Opinions of Emma” that Austen herself solicited from her friends and family, comments that have long been valued for the insight they give into the reactions of everyday English readers. Austen’s informants, too, concentrated on responses to particular characters and comments about how much they enjoyed, or did not enjoy, reading this novel. While several of Austen’s acquaintances shared the American annotator’s dislike of Emma (“intolerable”), the English readers responded more positively to Mr. Knightley than did the American, who found him only “tolerable.” None of Austen’s circle agreed with the American’s approving view of Harriet, Frank, or Jane. And no one among Austen’s sources mentioned Mr. Woodhouse, while all praised the characterizations of Miss Bates and Mrs. Elton, which the American did not appreciate.

The American annotators’ low opinion of Emma overall was shared by a few of Austen’s informants. One, Mrs. Digweed, candidly remarked that she “did not like it [Emma] so well as the others, in fact if she had not known the Author, could hardly have got through it.” Another, Mr. Cockerell, “liked it so little,” Austen recorded, that her niece “Fanny wd. not send me his opinion.” Yet another, Mr. Fowle “read only the first & last Chapters, because he had heard it was not interesting.” At least the American readers did make it all the way to the end of this novel, even if they celebrated their relief in having finished it!

Of course, these two sets of comments differ in several ways beyond the readers’ nationality alone. Austen’s informants summarized their thoughts after completing Emma, while the Americans responded as they read. Most of Austen’s sources were familiar with her other works and drew comparisons with them, which the American readers did not (or could not) do. With the exception of the few readers whose ideas were forwarded to Austen by mutual friends, her informants were speaking to her in person, as opposed to writing anonymously in a borrowed copy. (Addressing Austen directly does not seem, however, to have especially inhibited those of her acquaintance who candidly expressed dislike for Emma.) Most significantly, Austen collected thoughts from many more than just two readers.

Given how little has been known about the responses of Austen’s early American readers, however, even two anonymous, contrarian annotators of a single novel make a valuable contribution to reception history. There is no better reminder than these unvarnished comments of how much dislike Austen’s novels elicited, in and shortly after her own lifetime, from some readers on both sides of the Atlantic.

__________________________________

From Reading Austen in America, by Juliette Wells. Courtesy Bloomsbury, copyright Juliette Wells, 2017.

Juliette Wells

Juliette Wells, Professor of Literary Studies at Goucher College (USA), is the author of two acclaimed books about Jane Austen’s historic readers and fans: Reading Austen in America (2017) and Everybody’s Jane: Austen in the Popular Imagination (2011). For Penguin Classics, she edited Austen’s Persuasion (2017) and Emma (2015).