Is There Ever a Right Time to Talk to Your Children About Fascism?

Kera Bolonik Considers Conversations with Her Five-Year-Old

There’s a sort of joke I used to tell my friends—a joke that’s not such an exaggeration—to succinctly describe my mother, about how she taught my younger sister and me European geography by recounting the way each country persecuted the Jews during World War II. (Austria? Birthplace of Hitler. Germany? The home of the Nazi Party, and the country he led—anti-Semitism central. Poland? Place of the extermination camps that helped to annihilate most of the Jewish population. And on.) My other not-exactly-a-joke I’d share: If Shoah had been on TV in the early 1970s, we’d have watched it right after Sesame Street. My mother left out few details when telling us about the Holocaust, and there really was never a wrong time to regale us with these gruesome stories. Which is to say, I can’t remember the first time I learned about anti-Semitism or Nazis or even bigotry, because I’ve always known about it—she hardwired it into my brain. I thought this was what it meant to be a Jew in the world, that this is how she was teaching us. I wasn’t wrong, exactly.

My mother was not a survivor of the Holocaust, but rather a survivor of survivors—her Polish mother spent her youth hiding from Nazis with her family in Siberia, subsisting on weeds and berries; her blond-haired, blue-eyed father mostly hid in plain sight, passing as a gentile, first fighting with the Polish army until they lost, then in the Russian army—until he made a subversive remark that landed him in a Gulag, working in a mine where he almost died. He lost both parents and seven of his nine siblings (his father and a sister before the war).

My grandparents met on a Polish train platform after the war, married quickly, and moved to a displaced-persons camp in Germany, where they had my aunt Aylin, and eventually took an illegal boat bound for Israel to start their new life—and instead landed in Cyprus. Their second attempt was successful—they ended up in Haifa, where they had my mother, in 1948, and stayed in Israel for nine years. Ultimately, though, they settled in Portsmouth, Virginia, in the late 1950s, much to my mother’s chagrin. Imagine the culture shock: a family of four Jewish, Yiddish-speaking immigrants living in a provincial, Southern, predominantly Christian American naval town. My mom told me a curious classmate, who’d never met a Jew before her, asked whether she had horns.

Life with her parents was so insular—she and her sister didn’t have sleepovers or otherwise invite friends over—that she had no reason to know that other people’s families weren’t haunted by visceral nightmares, nightmares that were less dreams than unspeakably devastating flashbacks to their very real past. Like my mother, my sister and I were raised in predominantly gentile neighborhoods—though, growing up in Chicago and, later, a liberal suburb, our environment was far less provincial than Portsmouth, and life at home, a bit less insular—my parents spent time with their friends (all young Jewish families they’d met from our nearby synagogue) and we regularly enjoyed cultural outings. But my mother zealously vetted our friends—that’s what the geography lessons were about: Chicago is a richly multicultural city, a refuge for, among other immigrants, Eastern Europeans, and some of my closest classmates’ parents hailed from Germany, Lithuania, and Poland. Those nations were, as she’d remind my sister and me, bad to the Jews. “Mom,” I’d say, defending one of my friends, “stop calling her dad the Führer, he fled before the war.” And: “Who is her mom going to rat me out to? My math teacher? We’re just doing homework!” (These “geography lessons” were partly my mother’s cynical sense of humor—she was being funny—but also a manifestation of a jealous streak: since she didn’t get to cultivate friendships as a kid, neither would we.)

When my mother married my father at nineteen and gave birth to me at twenty-two and my sister three years later, how could she not pass this mindset on to us? I believe there is truth to the studies about how traumas like the Holocaust and slavery are woven into our DNA, passed down for generations. Being such a young parent, sprung straight from a household like hers, at a time when people rarely if ever unpacked family traumas on a therapist’s couch or even pored over parenting books besides Dr. Spock’s, my mother wasn’t raised to have a filter. No one to rein her in or tell her that maybe you should wait to discuss such matters with your children until they’re a little older. This is how you raise Jewish children in America, no? To make sure they never forget?

Or is there nothing to forget because it never went away? I think about what James Baldwin said at the National Press Club in 1986, a year before he died, words seared into my brain because now more than ever I am reminded of how true they are: “History is not the past,” he said. “It is the present. We carry our history. We are our history.”

Because here’s where my mother succeeded, though there were times when I was growing up I found her to be overly dramatic, self-serving, even myopic: she impressed upon me that hatred never goes away—its manifestations may lie dormant but still it enacts itself in a number of ways—like microaggressions and casual bigotry, though we didn’t have those in our lexicon at the time. It wasn’t all epithets and graffiti on houses of worship, or physical harassment or worse. It could be subtle—euphemisms, jokes, condescension, cultural erasure, general invisibility. I remember using terms like “out Jews” (to refer to my family) and “closet Jews” to refer to classmates—language I’d rediscover when I came out as queer in college—because very few of my Jewish classmates were as eager to identify themselves as I was. My mother repeatedly told me that when the economy tanks, scapegoating has an awful tendency to creep back, and that in fascist-run or -infested nations, citizens become complicit—and that they have to be. It was terrifying to imagine that people I knew, people I was related to and loved, could be so loathed that they had to flee or go into hiding, that they were treated like chattel, slaves, lab rats, that they were starved. That their families and friends didn’t all make it, that some were gassed to death en masse. But, I admit, it lacked an urgency in my mind no matter how much my mother drilled it into me: it wasn’t now, it was two generations earlier. Because I had both parents who didn’t have that direct experience, and I was living in the suburbs with creature comforts, it seemed like we were past that, that it was a lesson learned, impossible to repeat. I had, I admit, a level of privilege that my immediate ancestors did not. I had no accent, I could decide whether or not to identify. I could move freely in the world.

But this summer, I watched in horror the Trump rallies—the first warning. And no sooner was this American Führer elected then we saw a spike in hate crimes. From the moment he was inaugurated this nightmare has quickly become realized with a barrage of vicious executive orders and treasonous, sinister, deliberately incompetent appointments. I should have never doubted my mother’s warnings that what happened in Europe in the 1930s and 40s could happen again, that it could happen here, a nation where so many sought refuge from fascist regimes (and so many were turned away). And so soon.

*

As I write this, it’s been barely two months into this administration, and my wife, Meredith, and I are bearing witness to this nightmare with our five-year-old black son, Theo: to travel bans and bullet holes through homes and synagogues. Cold-blooded murders of Muslims, and those presumed to be Muslims. ICE agents rounding up Latinx immigrants for deportation, often separating them from their children. Adults and kids tormenting people of color because they feel they’ve been given license to yell “Build That Wall” to Mexican people, to rip hijabs off Muslim women’s heads, to tell black and brown people—fellow citizens, even—to go back to their country of origin, to threaten Jews that they’ll cast them into ovens. We are bearing witness to near-daily bomb threats at synagogues and JCCs. Mosque burnings. Desecrations of Jewish cemeteries. Swastikas on synagogues, playgrounds, people’s houses. Recruitment flyers on college campuses by Aryan and Nazi groups. Lawmakers proposing bills to starve public housing and schools of billions of dollars of funding. And complete silence from the president, with his Judenrat son-in-law and daughter, and his anti-Semitic, Islamophobic, xenophobic, racist, Nazi-affiliated senior advisers. I’m too scared to ask how much worse it can get, because it can and will get worse.

I’m not shocked that we’ve arrived at this place. For so many communities this has always been America—if you’re black, or Muslim, or Latinx, or an immigrant. Or a woman. Or LGBTQ. Because we as a nation have never reckoned with our white Christian male supremacy, the stage has been set for the current racist-in-chief (slash traitor slash rapist slash grifter slash pathological liar slash illiterate sociopathic narcissist) to come along. But just because many of us know how it happened doesn’t make it any less frightening.

So, no, my mother wasn’t wrong to start this conversation so early (though I’m thinking she could have eased into it). It’s more that I am trying to figure all of this out now, as Meredith and I raise Theo in a country built from forced labor, on stolen land, one whose history has always been brutal for those who are not privileged white or Christian or cis-male or heterosexual. And now it has been made exponentially worse with the election of a fascist making good on every ugly campaign promise.

Even before we spoke of him, our son already knew Trump’s name, recognized his mug—he lurks in the air like smog. He told us, “Trump is a really bad guy”—as if he were the Joker, or some other villain out of a comic book. At the time, our son was in his second year of preschool—the year before kindergarten—and he and his friends were enamored of the good guy–bad guy dichotomy as they had just discovered superheroes and Star Wars. Now, as then, Theo doesn’t fully grasp what makes Trump despicable, nor does he know what led him to the Oval Office—the racism and racial resentment of a huge faction of white Americans who felt so threatened by a black man in power for eight years that they stocked their arsenals with semiautomatic weapons, openly carrying them in malls and restaurants, and launched the Tea Party movement, which has metastasized from school boards and statehouses all the way to Washington. So when and how do we start that conversation?

I sought the advice of other mothers of black sons when the “bad guy” play at preschool heightened and the kids were putting their toys in jail, building jails with Magna-Tiles and blocks, turning jungle gyms at the playground into “jail”—which the teachers found as dis- turbing as some of the parents, like us, not least of all because nearly every day, another person of color was being brutally beaten or murdered by police. My friend Kirsten West Savali, who is the mother of three boys, gave me advice that sounded the most familiar to me: “I think being proud and confident of blackness is linked to understanding racism. The framework of racism and privilege are already there. It’s important for them to know that they are enough, even when the world tells them they’re not.”

I take what she says to heart—I think she’s right, and it essentially echoes what my mother believes. But I haven’t brought myself to enact it quite yet. In part because it’s more frightening—what my mother told me, and when she told it, felt abstract, like past tense, because I wasn’t seeing anti-Semitism play out before my eyes. But racism is ever present. It isn’t just an integral part of American history—it is, in many ways, the story of this country, and it never went away and may never go away. And, inevitably, Theo will learn that the hard way, and I dread it. But we have to talk to him about it, preferably before that happens. We’ve started to, in a way.

My concern is that I don’t want to braid racism so tightly with racial identity the way my mother proudly did anti-Semitic persecution and Judaism—but I worry that that’s my white privilege talking. So Meredith and I are working on figuring out how to strike that balance. We adopted Theo when he was a newborn, five months before Trayvon Martin was murdered. I was 40 and she was 41 and we had spent years thinking about what kind of parents we wanted to be—call it one of the rare lesbian privileges, planning when and how to have a child, with no risk of accidentally being thrust into parenthood too soon. But you can only plan so much before you know who your child will be.

I will never forget the first question his birth mother asked me when we spoke two months before he was born: “Are you sure you want a black, African-American boy?” At the time I took her question at face value, vigorously assuring her that we absolutely did, that we would love him like crazy and give him the best possible life. Still, we had to reckon with the reality that he would be living in a white household— living with two white women, with two sets of white grandparents, but thankfully a racially and culturally diverse chosen family of friends, in Brooklyn. Would we be able to make him feel like he’s not always the only brown face in the room? We would have to make sure of it.

After Trayvon was murdered, I started to think about Theo’s birth mother’s question, wondering if I’d misinterpreted it: Was she really asking if we knew what it meant to raise a black son? I ask myself this question every day—wondering about both the meaning behind her question and whether Meredith and I have the answer, whether we’re doing right by our son.

Last year, we recognized in Theo’s “bad guys” conversation—and Trump, for that matter—an opportunity to introduce a conversation about racism with Theo. He was four—a young four—but he had opened the door to it because of those new games of tag at the playground: everyone divided into good guys (cops), and bad guys (criminals) who, when tagged, were sidelined in some sort of make-shift jail. Theo, who loves to run, liked tag, but he wasn’t much interested in cops or guns—he still isn’t—in part because unlike a lot of white parents of white children, we have never told him to seek the help of a police officer if he’s in trouble. What is a bad guy? What is jail? he wanted to know. Now we were able to broach the topic of police brutality and race, a conversation we will be revisiting time and again—and the difference between making bad choices and being an actual bad guy, which is rarer. And that, too, was our first acknowledgment of Trump in our household.

At the time, despite the warnings from black friends and pundits, we really believed Trump was more of a fluke than a threat to our government—though the hate he dredged up at his rallies was another matter—so I felt comfortable telling Theo that the man we’ve come to call the Orange Menace was a bad guy. Meredith and I explained that not all bad guys go to prison, even when they do bad things, even though they should—like Trump. And that there are good guys who make bad choices, and good guys who get blamed for bad things they didn’t do, and these good guys do go to prison. And sometimes they even get shot by cops. And none of this is fair. “Fair” and “unfair” were words he understood, though I’m not sure what else he took away from the conversation—but it was a good start. We followed it up by taking him to his first rally, for Black Lives Matter, following the murders of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling.

Now Theo attends a public elementary school where white kids are in the minority in his classroom—his classmates are black, mixed race, Latinx, and more than a few are first-generation Americans. One of the first lessons they learn—and revisit throughout their years at the elementary and middle school—is how to be an ally to one another. The election results were treated like a terrorist bombing by the administrators, who sent several emails throughout the day to parents about how they would discuss the results with the students, a follow-up about how they responded, and another to invite parents to come in and unload.

In our household, as the election drew closer and the race grew tighter, Meredith and I had an understanding that we would not talk about Trump—we found it more exciting to focus Theo’s attention on the possibility of having our first female president. I remember telling him, “One day you’ll grow up and be like, ‘Whoa, the first two presidents I ever knew were our first black president and our first female president!’ How lucky, cuz Mommy and me, our first president was a guy named Nixon, who was a crook.” I should have taken it as a sign.

The conversation we began over a year ago continues—we’ve been reading together about the civil rights movement of the 1960s and are working our way backward in history—and I’m grateful that his school engages in these discussions with the students and their parents. There will come a time, very soon, when he’s going to learn about slavery—as with delving more deeply into racism, I hope we can broach the topic first. Because we dread the day he first hears the N-word and other epithets. Will we have prepared adequately when he’s bullied by other kids, by authority figures, by people in power? Will he be ready? Can we protect him, or will he be able to protect himself?

Since the election, we’ve taken him to a couple of rallies around the city—for, among other things, racial justice, and against the Muslim ban. We taught Theo to throw his fist straight up and say, “Black lives matter!” “Resist!” and “No ban, no Wall!” In doing so, I realized what it was that my mother forgot to instill in me, what I thankfully discovered on my own, and what Meredith and I may be correcting, what we can correct: that we can pair difficult, vicious truths with action and community, and that lends a genuine sense of hope. It’s imperative to confront the brutal reality of racism—and anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, xenophobia, misogyny, homophobia—that toxic blend of hate and fear. And it is unbearable to consider that an embittered, incompetent failed businessman, a grifter, a fascist, and a traitor, holds the most powerful job in the country and one of the most powerful in the world—in the ultimate display of white male supremacy and insecurity. But confronting these bitter truths doesn’t need to wholly define us—because it’s too easy to succumb to despair. We can’t let that happen to Theo’s beautiful soul.

My son has dreams of growing up to be a parent—he’s talked about it since he was old enough to articulate it, and we want more than anything for him, and his generation, to have that and more. To have a glorious future. We are eager to impress upon him, especially now, that when there is injustice (and when isn’t there?), he has a voice, that he can rise up. That protest is powerful, that resistance is powerful, that when people join together to fight for justice, it is not only effective but can restore hope for the future and faith in humanity. I’ve not seen him feel discouraged (except by his math lessons) or genuinely terrified—not yet—but we have seen him feel buoyed, positively energized by being in the company of passionate activists at actions he refers to as “parades.” And boy, does our kid love a parade.

__________________________________

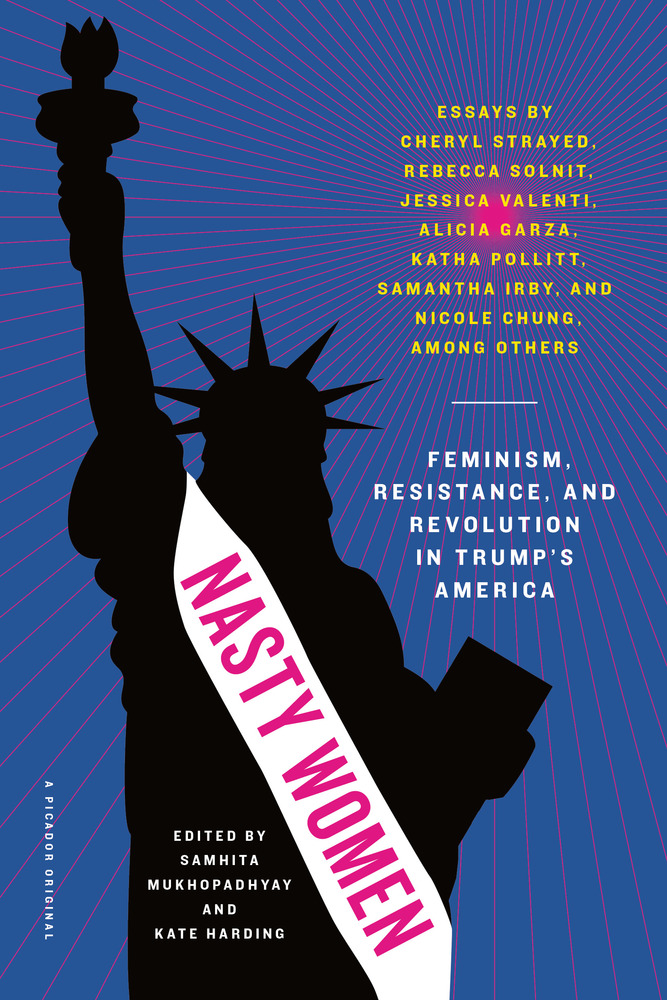

From Nasty Women: Feminism, Resistance, and Revolution in Trump’s America, courtesy Picador.

Kera Bolonik

Kera Bolonik is the executive editor of DAME magazine. Her work has appeared in New York, Glamour, Salon, Slate, the Village Voice, and The Nation, among other publications.