Iowa City, 1992: A Social Network

Heartbreak, Fame, and Beers at the Fox Head

In my memory, the mariachi horns from Johnny Cash’s “Ring of Fire” are wailing from the jukebox every time I walked into the Fox Head. It was already a Workshop institution when I arrived in Iowa City to start the M.F.A. program in fiction in the fall of 1991; there was no lore passed down from class to class about the first writers who had claimed it for the Workshop, or any discussion about what made the Fox Head a better writer’s bar than, say, George’s, just a block away on East Market, where you could get a decent burger in a basket at 1AM. You just went.

The Fox Head had a jukebox heavy on the sad white crooners. It had a pool table that ran on quarters and played tricks with its dimensions: at times, floodlit by billiard lights and crowded by the booths, it looked like the smallest pool table in the Midwest; at other times—if you’d been there too often in a week—it seemed to sprawl out over the length of the bar like a green felt fairway. The draft beers were cheap, and most of the liquor was off-brand. It was a place without pretention, a boxcar-shaped oasis in a Big Ten college town from the vast conspiracy outside, the “moronic inferno,” in Saul Bellow’s words, that sought to kill off literature through indifference. You went there to be a writer, among other writers, and to live out the fantasies you had concocted in your mind about how writers conduct themselves, how they live.

Most of all you went. Sometimes just one night a week; sometimes five or six. It depended on how lonely you were, how much you needed the attention. I didn’t drink then, which made it easier to be a regular. And harder, since I had no way of easily forgetting what had happened at the Fox Head the night before (or didn’t).

Love is a burnin’ thing,

And it makes a fiery ring

Bound by wild desire

I fell into a ring of fire.

At the beginning of my first year, while I was still awed by everything that writers did—everyone in my workshop spoke a whole new language; the stories they wrote all belonged in print (this was one of the pronouncements I learned to make: “It belongs in print”)—a second-year student gave me a piece of advice. We were lingering by the bar at the Fox Head while he waited for his beer. I was sipping Coke from a glass bottle. It was one of those intervals, well into the night, when the action stopped, the clamor of the bar receded into background noise, and it seemed possible, for those who had the gift, to see right through the confusing swirl of life around us: to workshop it. Johnny Cash, or maybe it was Hank Williams, sang woefully on the jukebox. The program’s director, Frank Conroy, was playing a game of pool in a tweed jacket and a pair of glasses that made his eyes look magnificently large, all-seeing. There were any number of love-related dramas playing out in the booths, a few I already had a stake in. This is what the second-year student told me:

“One day,” he said, “you’re going to have a bad time in workshop. A really bad time. Maybe Frank is in a foul mood and you’ve pissed off a few people around the table for whatever reason—your insufficient love of Richard Ford. Some comment you made in workshop about their use of water imagery. I don’t know. They decide to go after you in workshop, and Frank sits back and lets it all happen with that little grin of his. It feels awful. I mean, really awful. You stew about it for a couple of days. You skip a class or two and keep a low profile. Then when you decide you’re over it, you come into the Fox Head. It’s the same. It’s always the same in here. Frank is playing pool, there’s a breakup in progress going on outside, someone got published in The Kenyon Review and they brought in a copy to show it off. You know the deal.”

“Right,” I said, in awe all over again. “Got it.”

“This time when you walk in the bar,” he went on, “it’s a little different. The order of the universe has undergone a subtle change. Your best friend? The only one who stood up for you in Frank’s workshop? He’s sitting alone in a booth with the girl you thought you were dating. They’re all over each other. They’re obviously fucking. They might as well be fucking right there, in the Fox Head.”

“Really?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “Really.”

“I guess I’ll watch myself,” I thought out loud.

He put a big-brotherly hand on my shoulder. “Don’ t get hurt.”

It might have been the truest thing anyone ever told me in Iowa City. But there was one more part that he didn’t mention: After you walked in the Fox Head and saw your best friend sitting with the girl you thought you were dating, you got a drink from the bartender, walked over to their booth, and spent the rest of the night in furious conversation with them.

I fell into a burnin’ ring of fire

I went down, down, down

And the flames went higher,

And it burns, burns, burns,

The ring of fire, the ring of fire.

This is all before Facebook. Before the tyranny of smart phones, tablets, and text messages. Most of us wrote on personal computers, but they couldn’t be folded up and carried with you to a bar—or the Hamburg Inn, the best place for breakfast after a late night at the Fox Head. “Sharing files” then meant meeting in person and handing over a 5.25 inch floppy disk. When you wanted to be in touch with a friend after you’d left the house, you either called them from a payphone, stopped by their house, or hoped you would run into them. If you wanted to run into someone from the Workshop (or even if you really, really didn’t), you showed up at the Fox Head. There were writers in the program who hardly ever went to the bar, of course, but they weren’t really writers. They were suspect.

I fell into a burnin’ ring of fire

I went down, down, down

And the flames went higher,

And it burns, burns, burns,

The ring of fire, the ring of fire.

Fame in the workshop, or maybe I should call it “celebrity,” could be won in different ways. The first anointing came when you were admitted into the program and given your financial aid package. At the top were those first-year writers who’d snared the fellowships large enough to live on and that didn’t come with a job like teaching, or working at The Iowa Review. That was my job: I was Fiction Editor of the magazine. It felt almost too fortunate to be reading fiction slush at the age of 22 and typing personal rejection letters when established writers sent us stories that we couldn’t use and had clearly made the rounds already (Joyce Carol Oates’s agent must have submitted a half-a-dozen stories in my two years at the magazine, the manuscripts embossed with the imprint of ghostly paperclips). This job placed me squarely in the middle of the pack, and everybody in the program knew it, while the writers on the better fellowships arrived in town with an aura about them—a kind of celebrity—that either grew in time or slowly wore away, depending on what they wrote. The anointed students walked in light, they had more money to spend, and it was news whenever one of them came into the Fox Head.

You could write your way to celebrity, of course, either from the bottom or the middle—your ranking didn’t matter on the page. The Workshop was egalitarian that way, and probably in that way only. If you wrote a story that flew off the shelves where the workshop manuscripts for the week were stacked, and Deb, the program secretary, had to go back for another round of photocopies, then you were golden. It meant the entire program was reading your work. The word had spread. “Hey, great story,” a writer you had never spoken with before might say in the hallway between seminars. Stress on “great story,” as if it were italicized. “I loved your story!” a voice would call out from afar while you were ringing out your groceries at the food co-op. With so much proximity to real literary accomplishment, is it any wonder that we had our own version? I once saw a writer burst into the student lounge and start high-fiving everyone in sight after the stack of his workshop stories had run dry. “Best seller!” he howled, only half in jest. “Time for a second printing, baby!”

There were other, darker forms of Workshop celebrity. The program didn’t work for everyone who came. It was in Iowa. You had lots of uninterrupted time to write—or not to write. There was no one keeping a word count. Except for you. It’s always easier, even with the guilt attached, to write nothing on a given day than face the blank space inside your mind, the limitations hiding in every sentence. That’s why so many writers publish early on and then wanly disappear. There were the Teaching-Writing Fellows (or “twifs,” the top-ranked students in the second year) who kept on workshopping the same stories they’d used to apply to the program; or the writer who gave up fiction in his first year, stopped coming to workshop, and only submitted pages from his blockbuster-style screenplays when his turn came; there were writers on brown-out everywhere, showing up to class, filling seats at Prairie Lights for readings and making regular appearances at the Fox Head, but caving on the inside from the hurt of writing for their lives and having the pages Xeroxed and distributed for scrutiny. You could see it in their eyes. They were all celebrities too.

The taste of love is sweet

When hearts like ours meet.

I fell for you like a child

Oh, but the fire went wild.

This brings me to my favorite memory from the Fox Head. There are others that come close, and many more that have vanished, but I can still see this night as clearly as the animated waterfall and red canoe in the Hamm’s beer sign that hung over my favorite booth. It was late in my second year, a muggy night in spring. I’d almost reached the end of the program and I’d had my fill. Of Iowa, the Fox Head—of everything. But still, I was there. Drinking Cokes and talking late into the night, until the entire bar felt like a boxcar that had unhinged itself somehow and started rolling free across the prairie. My friend Alex had arrived at the program, a year behind me, as one of the celebrities. He’d been a go-go boy in San Francisco, the story went. An agitator and bomb-thrower for Act Up. He was about to be voted, in a landslide, our Prom Queen. He’d come to Iowa to get serious about his fiction writing, and he had single-handedly changed the chemistry of the program, broke the dominance of the traditional story and given the rest of us—the ones who thought “meaning, sense, and clarity,” the program’s mantra, was dangerously limited—a fighting chance. It felt like that, anyway, especially at 1AM in the Fox Head.

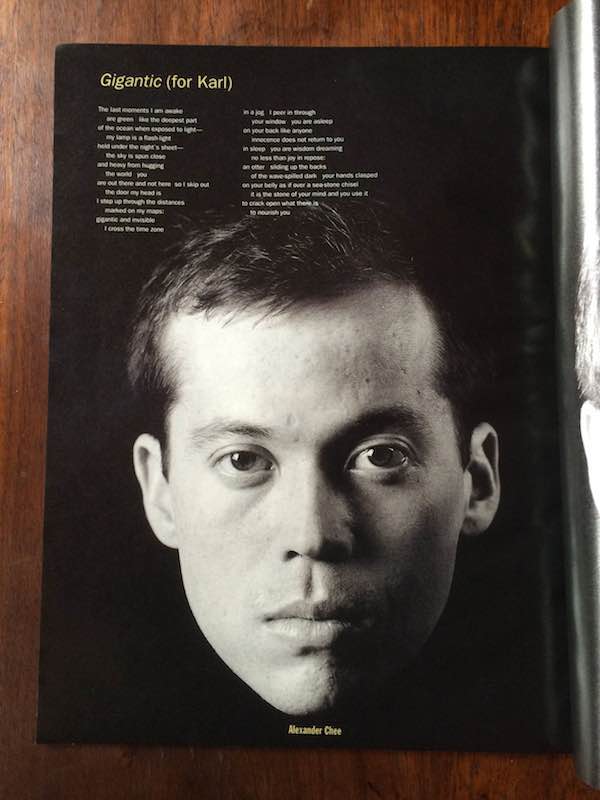

That night, Alex had come into the Fox Head, triumphantly, with an issue of Interview Magazine. I’m going to go out on a limb and say it was probably the first time anyone had brought a copy of Interview into the Fox Head—but that doesn’t mean it couldn’t have happened. The Fox Head was indifferent to the culture wars. Interview had put together an “emerging poets” issue, and they’d published one of Alex’s poems—called “Gigantic,” after the Pixies song—with a close-up portrait by one of the magazine’s stable of photographers. Alex’s face, shot in black-and-white, filled an entire page. It was a celebrity shot. From the world outside. One of us had made it. That photo created a buzz in the Fox Head that night like I had never before seen or heard. There was grumbling in the booths, of course: Alex wasn’t even a poet! He wrote fiction! Interview was a magazine devoted to celebrity (said with a sneer) and we were writers! What did anyone at Interview know about poetry? I watched it all unfold from my booth across the glowing green pool table: Alex sat with a beer and his open magazine, playing host while, one after another, all the writers in the bar that night slid into his booth to see the issue for themselves, to congratulate him.

I can still see that photo of Alex’s face lying facing up in the booth, hovering there while the jukebox played, and I marvel at the power that it had over all of us, the way it humbled a bar full of writers and amazed away our envy, our scorn, and compelled us to pay tribute.

I fell into a burnin’ ring of fire

I went down, down, down

And the flames went higher,

And it burns, burns, burns,

The ring of fire, the ring of fire.

When Alex posted his Interview portrait on Facebook a while back, I couldn’t help noticing how small it looked in his feed, and wondering where all of its terrible power had gone. I don’t mean “terrible” in the bad sense; I mean in the way it drew us to our knees. The way it captivated us, collectively. We were at a bar where all of us did a sizeable proportion of our living. Where we learned, at least in part, how a writer was supposed to live. The Fox Head was our Internet. It was our Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. You went at night because you couldn’t stay away, because you didn’t want to miss anything that was happening—it could change your life—and the hunger for going to the Fox Head was more powerful than your resistance.

Alex invented the Facebook post that night in Iowa. I think he did.

I fell into a burnin’ ring of fire

I went down, down, down,

And the flames went higher,

And it burns, burns, burns,

The ring of fire, the ring of fire.

The second-year student who took me aside to warn me about the Fox Head? He was right. His powers of prediction were eerily accurate. Except he was the one who I ended up seeing in a booth one night with the writer who I thought I’d been dating. I hung back for a little, loathing the jukebox and trying to get my feelings together, then I ordered another Coke from the bartender and slid in the booth across from them.

And it burns, burns, burns,

The ring of fire, the ring of fire.

The ring of fire, the ring of fire

The ring of fire

Benjamin Anastas

Benjamin Anastas is the author of the novels An Underachiever’s Diary and The Faithful Narrative of a Pastor’s Disappearance. Other work has appeared in Harper’s, The New York Times Magazine, Bookforum and The Best American Essays 2012. He teaches at Bennington College.