How Surviving ‘Ex-Gay’ Therapy Made Me a Better Writer

Garrard Conley: "I wrote and rewrote again. I wrote in doubt and fear."

From the ages of 13 to 19, I wrote stories with abandon. Petty, threadbare murder mysteries inspired by a summer of reading R.L. Stine. My friends and I would spend afternoons buried in overpriced Moleskines, reading stories aloud in the evenings, trading notebooks so we could put a new “spin” on one another’s plots. Spins, twists, cliffhangers: our words reached for the expected unexpected. Our genius formula involved what we thought of as reinventing the genre. You know how the killer is always the husband? What if the killer was married to himself, only you didn’t know this until the end of the story? Kind of like Psycho but better.

Finishing a story was a high. In order to reach that high as quickly as possible, I’d throw in an explosion or two, resurrect a long-dead father, kill off the main character, make her a martyr. During those years when I began to discover an attraction to other boys, these stories were my safe space. No one in our Baptist church ever asked what I was writing or reading unless it was a high-profile book like Harry Potter, once referred to as a “seducer of children’s souls” by a visiting revivalist. No one seemed to care how I spent my free time as long as I publicly professed Jesus Christ as my eternal Savior. I was able to stave off any realizations about my sexuality by imagining other lives, other realities, attaining that next writing high.

But then, just before I went off to college, my father became a full-time preacher. He claimed that everything in his life had been building up to this moment, that nothing else mattered now except bringing “thousands of souls to the Lord.” He was to be publicly ordained in our church, his family life scrutinized by the Baptist Missionary Association, and his wife and son were to stand on the sanctuary stage in front of hundreds of God-fearing Christians while he took his vow. It was a twist my mother and I never saw coming. Sure, my father had been a devout believer all these years—we had always gone to church three times a week—but my father’s newfound fanaticism (a word we would never use in front of him) seemed to shine a spotlight on every part of our lives. In what felt like a Hidden Object hunt for our family’s Seven Deadly Sins, congregants wanted to know when my mother had bought her new ring (greed), how often my father worked on building his hot rods (pride), how often and what kinds of video games I played (sloth/lust), and what exactly I was writing/reading all the time (all seven).

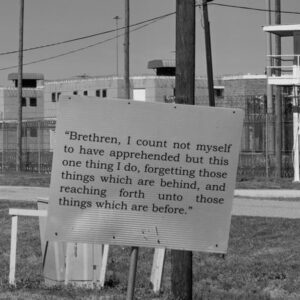

So when I was outed to my parents by a college roommate after a semester at a liberal arts college not far from home (oasis for all queer Southern kids), my parents, fearing word would get out, enrolled me in an “ex-gay” reparative therapy program called Love in Action in Memphis, Tennessee. Fearing abandonment and a lack of college funding, I agreed to attend a two-week trial program the following summer. The timing would mean we’d be cutting it close, but the plan might just work: a week into therapy, I would attend my father’s ordination as a Baptist preacher, and if the cure stuck, no one would have to know about my “struggles” with homosexuality.

During this waiting period I wrote ravenously, obsessively, striving after a post-writing high that would lift me out of my shitty life. I wrote stories I never let anyone else see, stories that acted out fantasies of death and regeneration and flight. I never once wrote a story that spoke directly about what was happening to me, never once wanted to touch reality, afraid I might be permanently disfigured by the process. My family was living out a very fucked up suspense story, an all too real Southern Gothic tale, and all the while I kept writing the expected unexpected.

The minute I arrived at Love in Action, I was stripped of all of my belongings “for the sobering process of reevaluation,” as my “ex-gay” handbook instructed. I was told the counselors were searching for False Images, or “any belongings, appearances, clothing, actions or humor that might connect you to an inappropriate past.” A blond-haired boy not much older than myself, a two-year patient-turned-counselor, took my Moleskine and ripped out all five pages of a story I’d been working on during the weeks preceding my arrival at the facility. “False Image,” he said, wadding the pages into a ball and tossing them in the nearest trashcan. It could have been the fact that my narrator was female, or it could have been that the story involved the murder of a teacher, but more likely the counselor threw my story away because it was just that—a story, a fiction, something he could neither fully control nor comprehend.

During the two weeks that followed, I was systematically stripped of every defense I’d ever had against the bigotry and shame I’d ingested from the church pew each Sunday. I was told that I was living a lie, that I had used art as an escape from my sinful nature, that I was “addicted to gay sex,” and that I needed to concern myself only with God and His forgiveness. At night I fantasized about ways of killing myself in order to escape the years of shame I now saw looming in my future. During our daily therapy sessions multiple people confessed to suicidal ideation, were subsequently shamed, and were made to recount Bible verses that hinted at suicide being the one unpardonable sin sure to send you straight to Hell.

Love in Action’s formula was a familiar one, an Either/Or mentality I’d encountered in church and, often, in the stories I read and copied in my own pieces. No matter what people went through before they were cured of their “sexual addiction,” the end result was always the same: a revelation, a reunion with Christ, a conversion that made the rest of your life’s story snap into focus. Just as my father had done with his life when he became a full-time preacher, shifting all the sundry details of his former years to line up into one clear path toward God, we “ex-gay” patients were being asked to view our “sinful pasts” as fodder for forgiveness, for making an honest commitment with God.

I’d heard the story repeated every time an ex-drug addict or an ex-gang member visited our family’s church to tell us how God had led them to redemption through pain. It was a story I’d once heard congregants tell a grieving woman who had just lost her child in a car accident. It was in the origin story of Christianity and thus a built in, trusted narrative of our culture: bad things happen so that we can learn from them. It was a story, I slowly began to realize, that I was done with. The expected unexpected, the epiphany, the enlightenment, the tidy ending that ties everything together—after two weeks of therapy, I decided to walk away from that narrative.

In the painful years that followed, I hardly touched a notebook. I stopped writing stories because stories no longer made sense. I was locked out of the Kingdom of Writing Highs. And during that time I believed that my own story provided no arc, held no weight or meaning, because I felt it only as a struggle with no clear resolution. I began to read with abandon rather than write with it, anything and everything that surprised me, brought me deeper into my struggle rather than away from it. Reading The Scarlet Letter, I was completely immersed in Dimmesdale’s plight, unable to reconcile the opposing forces in his life, unable to chart a clear path to his freedom. Reading Notes from Underground, I encountered this paralysis once again and was relieved rather than frustrated when the Underground Man cried out to Liza “They won’t let me… be good!”

I learned to truly empathize with another individual’s struggle, to view every minute detail of a human life as precious, often related but not always bound to a moment of clear catharsis. Rather than believing that the struggle was “part of God’s plan,” I began to see it as the very substance that makes up a life. Reading such untethered, unknown stories, I began to take my own life’s struggle more seriously. I began to confront my parents about what had happened to me, to argue with my father about his views on the Bible, to sit in the uncomfortable places I had carefully avoided for so long.

This long process of careful observation and exploration was what finally allowed me to write my own story. After nearly a decade of floundering, of giving up all hope of ever enjoying the process of writing stories again, I discovered a narrative voice that compelled me to write. I no longer wrote with abandon. I no longer wrote toward a pat ending. I wrote in small, hesitant bursts. I wrote and rewrote and rewrote again. I wrote in doubt and fear. I wrote with the knowledge that following this story was the only way I knew how to save myself from the true horrors of this world. The idea was scarier than any clown wielding an axe, any maniac bent on stabbing the babysitter, not because these creatures of terror are any less real than the terror I experienced growing up, but because they have always been easier to kill off.

Garrard Conley

Garrard Conley’s debut memoir, Boy Erased was released by Riverhead Books this month. Conley’s fiction and nonfiction can be found in The Common, The Madison Review, The Virginia Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. He has received scholarships from the Bread Loaf, Sewanee, and Elizabeth Kostova Foundation writers’ conferences. He currently teaches English literature at the American College of Sofia and promotes LGBTQ equality in Sofia, Bulgaria.