How Shirley Jackson Makes Us Lose Our Minds

Ottessa Moshfegh on Insanity, Mistaken Identity, and the Dark Tales

On three separate occasions, I stood within feet of people I knew intimately—one a best friend since adolescence, one a former lover, and one a member of my family—and I did not recognize them. Rosie who lives in Massachusetts suddenly appeared at a reading I was giving in California, and I thought, “Why is that girl staring at me like that?” A man I had lived with once in Brooklyn sat across from me in a coffee shop in LA, and all I could think was, “He’s strangely attractive.” A green-eyed woman in a silk scarf approached me at the Port Authority Bus Terminal and said my name, smiling. I looked at her and thought, “My mother is at least two inches taller than that woman,” then turned and kept searching for her face in the crowd.

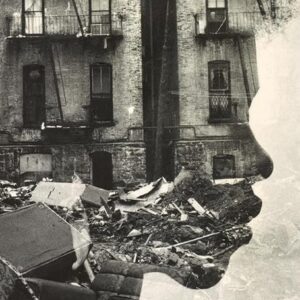

There is a peculiar malfunction in the brain, I think, when something deeply familiar appears in a strange context. And in fiction, this malfunction can turn into a ride through a new dimension of possibility. A character’s misperceptions can actually transform her world: paranoia is no longer a state of mind. The conspiracy is real: the girl at my reading isn’t Rosie at all, but a doppelgänger sent to make me lose my mind in a public forum; the man in the coffee shop and I fall in love again, and all the while I’m afraid to let on that I think I know him from before—he looks just like Jeremy, talks just like him, but says his name is Andrew. Maybe I’m crazy, and some evil spirit has taken the place of my mother—swapped bodies with her on the Greyhound bus, perhaps. Here she comes, this strange lady in a scarf, to taunt and beguile me, and to steal my soul.

After reading her Dark Tales, I think of these occasions of failed recognition as Shirley Jackson moments. In each story in the collection, the everyday world becomes tinted with an odd sheen of terror. My faith in the consistency of day-to-day life wanes as I read. Though Jackson often starts off rather benignly—her characters are never panicked from the get-go, but snake their way into states of dismay—she has a mystifying knack for illustrating the horrifying uncertainties around the basic laws of reality. Am I alone in doubting that things aren’t always what they seem? Upon awakening, I often ask myself, “Who am I? Where am I? What am I doing here?” and from time to time, I’ve felt that the answers were merely memorized responses, and that my reality might be an arbitrary dash of the imagination—believable, sure, but not entirely trustworthy.

This specific vulnerability—of the conscious, willful mind—is precisely what Jackson titillates and exacerbates in her stories. Identity, in particular, becomes flimsy and uncertain in her hands. In “The Beautiful Stranger,” for example, a man returns from a business trip, but is not quite sly enough to convince his wife that he’s the same person he was before he left. Similarly, in “Louisa, Please Come Home,” a runaway returns to her family after years living under an assumed name, but her parents have been so disabused by the fantasy of her return that they don’t recognize her. “What is your name, dear?” her mother asks her. It’s not quite a case of mistaken identity, but the cruel perversion of perception and memory under duress. Don’t be hypnotized by the sanctity of the superficial rhythm of humdrum life, Jackson warns, for under the surface of things, people change, sometimes irrevocably, and yet they may appear unaltered.

At other times, Jackson seems to be writing about the illusory trick of fiction itself. In “The Bus,” a woman’s complaint to her bus driver prompts him to leave her stranded at night on an empty road. Her misadventures in search of safety and sanity take the reader on a surreal exploration of what might be just a slip of dark reverie, a bad dream as she’s dozing off in her seat—she did take a sleeping pill before she boarded the bus, after all. Or, we wonder, is she actually trapped on a circuitous passage around the hell of her own grumpy psyche? Is the story real, or a parable for her frailty as an aging curmudgeon riding toward death? It’s often unclear in these stories whether the eerie peaks and turns are happening in the mind or in actuality. Either way, the experience of existential insecurity is very exciting as a reader.

“Shirley Jackson has a mystifying knack for illustrating the horrifying uncertainties around the basic laws of reality.”

And it seems, too, that Jackson’s characters are in on the game—one’s mind always operates in the hypothetical. Fiction and fact are only delineated in the present moment. In “What a Thought,” a housewife sits reading a boring book and fantasizes bashing in her husband’s head with a glass ashtray. Shocked by her own violent vision, she reels into reasons to not kill him, as though to convince herself to not do it: “What would I do without him? she wondered. How would I live, who would ever marry me, where would I go?” And the next moment, Jackson delivers this bit of fascinating science from the would-be murderer’s point of view:

They say if you soak a cigarette in water overnight the water will be almost pure nicotine by morning, and deadly poisonous. You can put it in coffee and it won’t taste.

“Shall I make you some coffee?”

Jackson’s narrators are not freaks or psychopaths, but actually very sane people—self-possessed, observant, and highly logical. In “Family Treasures,” for instance, an orphaned young woman in a college dormitory systematically pilfers cherished objects from her housemates, then uses her status as a heartbroken stray to manipulate the search for the thief in every misdirection. There’s a lavishness of reason in that story—I don’t think it’s any coincidence: clarity is truly terrifying—but there is also a perversion of sense through the narrator’s self-talk and doubt and analysis. The mind runs, and its course is often rife with pitfalls.

In “Paranoia,” a man leaving his office for the day debates with himself about what method of transportation he ought to take to get home in time to have dinner with his wife for her birthday. The mundane anxiety over his commute mounts. As his mind swirls, his senses betray him, and he comes to believe that he is being followed by a stranger in a light hat all around the city. He evades the man in fumbling swoops via bus, taxi, subway, and on foot through the bustling streets of Manhattan, a menace on every corner. But is it the same man in a light hat that he keeps running into? It seems impossible. The protagonist has clearly lost his mind. But by the end of the story, his delusion has superseded his suspicion and becomes the truth in the fiction: the man gets home and his wife is in on the conspiracy to capture him—why? We don’t know. She pretends to go to the next room to make him a drink and calls someone on the phone—the man in the light hat, we suppose. “I’ve got him,” she says. It’s terrifying.

And so Jackson asks: Dear reader, have you, too, lost your mind? Can you ever be sure you had one to lose in the first place? Have you ever mistaken the mew of a cat in heat for someone being murdered? Have you ever thought you saw your own self waiting at the crosswalk as you drive past in your car? Do you trust your own perceptions? And how far will you walk down a road at night before the wind at your back feels like the hands of a madman pushing you forward? Will you run? How fast? And whose door will you knock on? Everything looks perfectly normal as you rush up the front steps, and maybe you’ve just been spooked, maybe you’re just being silly. In Jackson’s world, the safe house is a trap. Enter it, and you might get lost in the dark.

__________________________________

Adapted from DARK TALES by Shirley Jackson, published by Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Foreword copyright © 2017 by Ottessa Moshfegh.

Ottessa Moshfegh

Ottessa Moshfegh is a fiction writer from New England. Her first book, McGlue, a novella, won the Fence Modern Prize in Prose and the Believer Book Award. She is also the author of the short story collection Homesick for Another World and the novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation, out now. Her stories have been published in The Paris Review, The New Yorker, and Granta, and have earned her a Pushcart Prize, an O. Henry Award, the Plimpton Discovery Prize, and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Eileen, her first novel, was shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Man Booker Prize, and won the PEN/Hemingway Award for debut fiction.