How Mapping Alice Munro's Stories Helped Me As a Writer

Elizabeth Poliner On the Shapes That Fiction Can Take

I first came to love Alice Munro’s stories for the resonance I felt with her subject matter—the close examination of the lives of girls and women; the tension she returns to again and again between the modest, rural place of her youth and the seemingly sophisticated world of the city, and the tension of being educated beyond one’s place of origin; the intricacies of family love; the implicit feminism of her worldview. One of the joys for me of reading Munro is how her work often makes me stop, pause, and re-see my life, especially the place of my youth—a small, working-class Connecticut town where most of my classmates ended their educations at high school, and where our Jewish family was such an anomaly—with eyes enlarged by the sensitivity of Munro’s stories. What gets me about a given Munro story—or at least the ones I love most—is how deeply I feel the material, an experience that has inspired me again and again to feel my way into the material of my own fictional worlds.

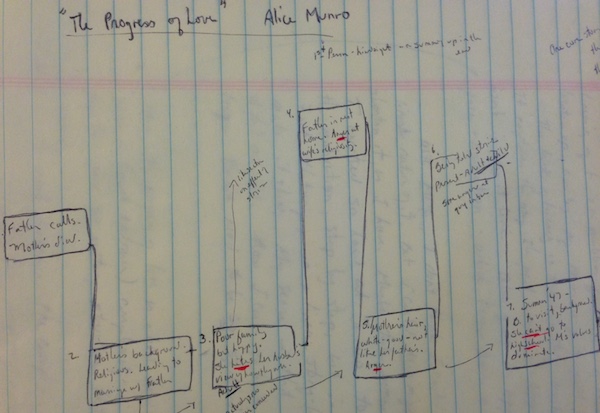

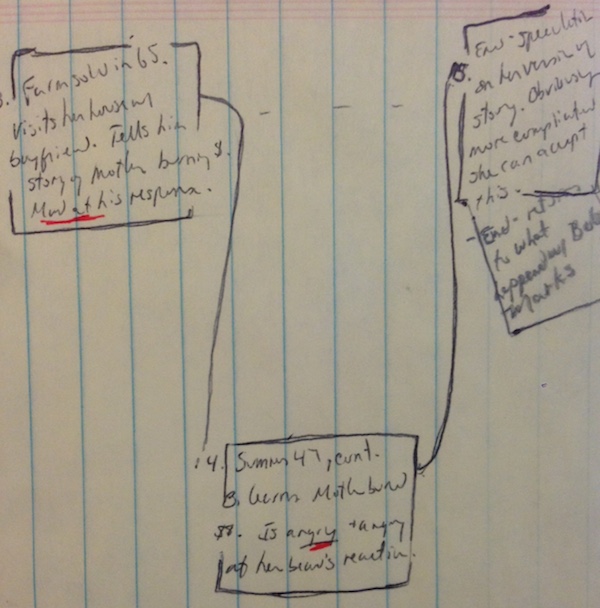

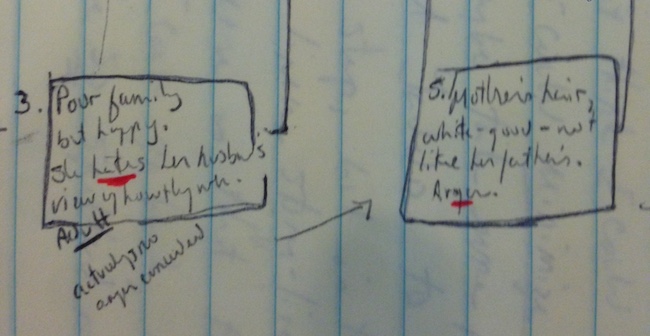

I was some years into reading her work, and some years—though not too many—beyond my MFA program, when I began to diagram some of Munro’s stories, specifically those sprawling mid-career stories that often move all over in time yet nevertheless hang together perfectly and read with utter and enviable smoothness. In their structural oddity and wonder, they don’t seem constructed at all as much as breathed into life. I wondered, on a structural level, what was really going on. How did she do it?

“The Progress of Love” was the first of these stories that I was determined to see and not merely read. I adored the story, particularly the way in which the female narrator is haunted by her relationship to her mother in a way her brothers never are, and I mapped its shape as best I could. By doing so what I discovered, to my intense delight, was a coherence even deeper than I had experienced when reading the story.

The story is of a middle-aged woman who looks back, mainly to a time in her childhood when an aunt visited the family, to understand the complex nature of the love, and hate, between her parents. Though the childhood remembrance takes up much of the space in the story, and is told pretty much linearly, Munro surrounds that tale with a strange, fractured movement in time whereby the narrator tells the story of her mother’s death late in life and her father’s reaction to that death, and about her own life, including a failed marriage and a middle-aged love affair. What I discovered as I diagramed the story—breaking it into sections and placing those sections on the page in a way that showed the movement of time—was that no matter where Munro went in time she was always dramatizing—or perhaps a better phrase is digging at—something almost beyond words, those subtle, hidden tensions that make love so hard, as well as the roots of those tensions, in this case a traumatic moment the narrator’s mother faced as a child. Not only is the movement of time in “The Progress of Love” complex, but the larger story contains multiple and conflicting versions of a story-within-the-story, that of the narrator’s mother’s traumatic childhood event. Oh, just writing that makes my heart beat fast! She’s a wonder, Alice Munro is. Who else can write a story like that?

A little something I picked up from diagramming this particular story, in addition to appreciating it all the more, is that when you move around a lot in time it can be useful to have one part of the story move linearly, like the backstory of the narrator’s youth.

It had been over a decade since I diagramed this story along with others, and I wasn’t consciously thinking of them when I wrote my novel As Close to Us as Breathing, but I must have internalized some lessons from the diagrams for in the end I wrote a story with a lot of movement in time, though at least one part of the story—the events of the summer of 1948—are told linearly. No matter where I went in time, I was always telling what I felt was the main story—how the struggle to be oneself in the confines of a tight social structure (a patriarchal, conservative Jewish family in 1948 America) blossoms and collapses depending on the broader social circumstances.

I had no plan for the novel’s structure, but felt it out, draft by draft, and in the end was quite pleased to discover (as if someone else had written the book and not me) that by the time a reader got to the novel’s end—a dinner scene among extended family members late in the summer of 1948—the reader would know everything about each family member at that table. The whole story would be told, previous to 1948 and subsequent to 1948, just as the story of summer of 1948 was coming to a close.

I once crossed paths with Alice Munro. I was living in Washington, D.C. at the time, and she was reading at the Folger Shakespeare Library on Capitol Hill where she was receiving a prestigious award for her short story writing. I went with a friend and remembered, as I typically don’t, to bring all my books of hers to sign. We sat nowhere close to where she’d be signing after the reading but when the event was over, by way of dashing and a certain amount of luck, we ended up second in what would be a very long line.

There she was, beautiful with her white hair, her headband worn 1920s style around her forehead, her pleasant face—not smiling but content, her slightly rounded shoulders.

I pulled a bookmark I’d made from one the books (I’m hoping now it was The Progress of Love). At the time I was in the habit of cutting watercolor paper, nice and thick, into strips for bookmarks and painting them. I held the bookmark in front of her and asked her if she’d like it. “Yes!” she said. Then I told her about diagraming her stories to see them better.

She paused. “They can take a long time,” she finally said.

I sailed home thinking I’d heard the wisest words ever about writing fiction. And that’s what I still think of them. When, like Alice Munro, you feel your way forward, sniffing and digging and groping toward a truth virtually beyond words, it takes a long time. And the structures, organic to that process, are as miraculous and indicative and expressive of that truth—one of the deeper truths of human life—that fiction is all about.

Elizabeth Poliner

Elizabeth Poliner is the author of As Close to Us as Breathing, a novel (winner of the 2017 Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize in Fiction and an Amazon Best Book of 2016); Mutual Life & Casualty, a novel in stories; and What You Know in Your Hands, a poetry collection; and Sudden Fog, a poetry chapbook. She is an associate professor at Hollins University, where she currently holds the Susan Gager Jackson Chair in Creative Writing.