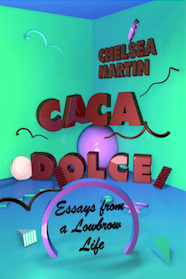

The Most Important Skill I Learned at Art School: How to Bullshit

Chelsea Martin on the Lessons We Take From a Fine Arts Degree

Because only a very small part of me wanted to move away from my friends and family, I applied to just one very expensive art college, figuring I would most likely not be accepted, and, if I were, I would not be able to pay for it and therefore couldn’t attend. Then it wouldn’t be entirely my fault when I inevitably got pregnant my first year out of high school and lived in blissful, blameless poverty and squalor for the rest of my life.

College was not an obvious next step after high school in Clearlake. It seemed like a rare, special privilege meant only for the special and privileged. From each graduating class of about two hundred students at my high school, ten or twenty went to college directly after graduation. My family didn’t encourage it much either. To us, it was something you might get around to after many years of work and raising children, and even then it was only night classes squeezed in after a full day’s work.

So, out of caution, I remained ambivalent about my future. I was equally ready to leave town and go to college as I was to remain living at home and start my lifelong career at Safeway, where my aunt Helen could probably get me a job.

But I got accepted to the art school I applied to. And found a way to pay for it, sort of.

I got a small scholarship from my high school and a pretty good scholarship from the art school, and those, along with government loans each semester, would almost cover the cost of tuition. I took out a private student loan for $15,000 to cover the rest of tuition plus extra for rent, food, and art supplies. I knew that $15,000 wouldn’t last four years, so I decided I would ride it out as long as possible, get part-time jobs to supplement that money, and figure out what to do when the money ran out.

I had never considered my family poor. In Clearlake, we had always occupied some middle ground between those who I now recognize were extremely poor, which was what I considered poor at the time, and those who were almost-not-poor, which was what I considered rich. In my mind, we were firmly middle class. This delusion was supported by the fact that we were able to rent a house with approximately enough bedrooms for everyone, that we ate dinner most nights, and that we were on welfare only when my mom was pregnant or nursing.

The first few months at art school dramatically changed my perception of where I fit in on the class scale. I was easily one of the poorest kids on campus. Of course there were other poors, like me. These were people taking on massive amounts of debt, who wouldn’t allow themselves to purchase a cup of coffee, and who wore clothes their grandma had bought them before their freshman year of high school. The poors blended in pretty well, though. Art school is a great equalizer. Intentionally insane and disgusting attire was expected and encouraged, found objects counted as fine art, and eating cheap microwavable garbage was viewed as good time management. Plus, no one assumes you are poor when you’re attending a college that costs $30,000 a year. No one is looking at you for clues of your poverty.

I watched and listened to my classmates carefully, waiting for them to drop clues of their wealth. A lot of them had been in art programs or art camps before attending college (things I hadn’t had the luxury of even having heard of), and had flown around the country visiting schools to decide which program they most wanted to be in. A lot of them had parents who had encouraged their artistic interests by taking them to museums and buying them art supplies that were not available in Walmart. Some had parents who were artists themselves, who had fostered artistic thought in their children from a young age. Many of them didn’t particularly want to be in art school, but had enough funds and pressure from their families to get a degree of some sort, and art school seemed like the easiest route for them to take.

I had so many questions about their wealth. Did they fly on private jets when they visited different campuses? Did they look at prices before ordering something from McDonald’s? Was going to McDonald’s something they even did? Did their families drink tap water or only sparkling bottled water? What was a trust fund? I didn’t ask any of them, though, for fear of exposing my own undesirable economic status.

The initial awe and fascination with my privileged peers turned into anger and resentment halfway through my first semester, when I got my first job. I worked at a specialty tea café from 4 pm to midnight three nights a week. It was a cute café and I liked the job, but I became incredibly jealous of everyone who got to spend those 24 hours studying, visiting museums, working on art, and socializing. I already felt so behind artistically and academically, and now I had to work twice as hard to keep up.

I was spending the same amount of money on my education, but I wasn’t really getting the same education. I couldn’t spend every night in the studio, because I had to stand in front of a cash register and make bubble tea and pretend that these things filled me with such joy that I couldn’t stop grinning and nodding supportively for my entire eight-hour shift. I couldn’t read my assigned class materials thoroughly because I often had to do it after work the night before class. And if I realized halfway through a project that there was a more interesting way to do something, or I had a better idea, I couldn’t afford to start the project over.

I knew these were rich-people problems. Only rich people could afford to complain about the lack of time they had to create still lifes of indoor flora and to read about Dadaists. Complaining about my rich-people problems made me feel whiny and spoiled and further separated me from my impoverished roots. I felt as hypocritical as the Dadaists themselves, who critiqued the materialistic bourgeoisie while making art that, like most art, only rich people had the resources to consume.

On the other hand, my problems weren’t exactly rich-people problems. Sure, rich people might complain about a lack of time to finish Dada homework, but not because they were busy working a minimum-wage job. Rich people might use their extra time to attend the new show at MoMA, or to network with Sophie, whose mother ran an arts residency and was looking for applicants from our graduating class, but I was trying to earn money to buy enough frozen single-serving lasagnas from Safeway to get myself through the week. In this way, I also felt alienated from my new peers, unable to be as smart or productive or connected as they were because I had to attend to my basic needs.

I was in an economic no-man’s-land, rich in education and opportunity, poor in money and time, with no one to complain to.

I took financial shortcuts wherever I could find them, stealing small portions of tea from my job after every shift, “dining out” at gallery openings every week, basing project ideas off of supplies I already had or could be stolen from the textiles department, and living in a bedroom the size of a medium-size closet. Then, inevitably, I’d have a weak moment, blow $45 at a fabric store, and make a mental note to beat myself up over it every time I made a student loan payment for the rest of my life.

I began to question my reasons for being in art school. Was I actually an artist? Was it worth the amount of money I was spending to figure it out? Did I need to be here even if I were an artist? And, if I wasn’t an artist, what exactly was I doing? These are common questions for art students, rich or poor. It isn’t easy to come to terms with the fact that artistically expressing intangibles is what you want to do with your life. It’s amazing to me that teenagers are encouraged to make these kinds of long-lasting decisions about their futures, are given what seems at the time like play money to follow their whims, are manipulated into betting future income on what they feel like doing when they’re 17 or 18, ages deemed years too young to be responsible enough to handle alcohol.

I remained in art school because, as difficult and expensive as these questions were, I had no other ideas for my life. Obtaining an art degree was a vague, nearly meaningless goal, but it was the only one I had. I’d already invested so much just by enrolling that I was determined to find some value. Maybe the next class I took would be the one to change my life. Maybe when I graduated I would be offered a glamorous art job. Maybe I needed to trust whatever misguided impulse had brought me to art school and saddled me with an unfathomable amount of debt in the first year alone, to see this thing through until I was absolutely bankrupt.

I couldn’t help but see each class I took as a dollar amount. I watched money borrowed from some hypothetical future self spill away as I tried to understand my poorly planned and ill-conceived academic and creative pursuits.

I took a $3,000 required drawing class and gained confidence drawing plants in charcoal.

I took a $3,000 Intro to 2-D Materials class that was mandatory for all students, and was required to do things like cut up pieces of paper and staple them to a tree and was reprimanded by my professor for not taking it seriously.

I took a $3,000 oil painting class and realized halfway through that I hated oil painting.

I took a $3,000 illustration class and a $3,000 intermediate illustration class and realized that maybe I didn’t really like acrylic or watercolor painting that much either.

I enrolled in a $3,000 textiles class because two of my friends were taking it. I liked weaving, so the next semester I took a $3,000 weaving class and a $3,000 advanced weaving class and after those I took a $3,000 jacquard weaving class and realized that I couldn’t imagine weaving for the rest of my life, that it seemed more like a relaxing hobby that I could do one day when I was rich enough to buy a loom and have studio space big enough to house it than an art form I was seriously interested in pursuing.

I took a $3,000 general writing class and loved it, so I took a $3,000 fiction writing class and a $3,000 literature class and a $3,000 creative nonfiction class, and was then told that I had taken classes in too many disciplines outside my declared major, painting, and would never graduate on time.

I was advised to finish my studies in painting, as I had almost enough painting and drawing credits to satisfy those graduation requirements. The writing and literature courses could be used to fulfill my humanities requirements. Or I could apply to be an interdisciplinary major, which would require me to convince a jury that my art practice was so nuanced and complicated that I needed the support of multiple departments. Unable to envision myself finishing school in the painting department, I chose the latter, even though I did not know how to present my work as interdisciplinary. Also, come to think of it: What work? The weavings I had abandoned the year before? The short stories I was just beginning to write? The paintings that I stopped making after my first year?

I was embarrassed that I had spent three years and more money than I could even conceptually fathom to figure out I didn’t like painting, that I kind of liked weaving, and that I was interested in writing. My mistakes were adding up.

I had spent more money on my education than anyone in my family or town had ever led me to believe I should spend on anything. I didn’t have the luxury of having a parent or society to blame for pressuring me to go to a fancy college. I had done this all on my own. I was to blame. I thought I could be an artist, but clearly I could not. Art was for rich people, people who could afford to take the time out of their lives to learn a craft, and I was financially ruining myself to learn this.

I felt guilty and stupid for attending such an expensive school when many of my high school friends were in community college waiting to transfer, or had already given up on the idea of college altogether and were still living with their parents, working at Walmart or the gas station or something. I was extremely lucky. I had so much privilege. Complaining even a little bit would be unappreciative and ignorant, I reminded myself. Over and over, I reminded myself how lucky I was.

I tried to stay confident and optimistic. Maybe I would have more to write and make art about than I would if money and experiences had been handed to me. Maybe there was some psychological benefit to working hard. Maybe my massive debt would be the fuel I needed to become a success. Maybe there were advantages to being poor. Maybe I was like the guy named Loser the Freakonomics guys wrote about, who was so burdened by his name that it became a motivating factor for making a good life for himself, surpassing his brother Winner in all standard measures of success. Maybe that was who I was—setting myself up to drown in debt so that I would have to become strong and have no choice but to succeed.

At the beginning of my last semester, I found out that my government loans had not been issued in the amount I expected, so I was $3,200 short on tuition. I was still working at the tea café and had also taken a nice-paying work-study job in the administration office, but my private loan money was gone, no one was helping me pay my bills, and there was no way I could afford a $3,200 payment on top of rent and bills and all the other grown-up things I was now responsible for. “Is there some kind of extra loan I could get?” I asked my financial adviser. There seemed to be no limit to the amount of money I would steal from my future self. If my future self became financially successful, I figured, $3,200 would be nothing to her. And if she were unsuccessful and continued to be poor, the exact amount of her debt would be irrelevant, as it was already so high that she would only ever be able to make minimum payments, if that, for the rest of her life.

“You’ve taken out all the loans you qualify for,” my adviser told me. “Maybe I have to drop out,” I said. I felt relieved at the thought, and also slightly badass, as if dropping out might add depth or authenticity to my personality, or harden me.

Yeah, that’s me, I dropped out of art school, I would say defiantly to my friends at the homeless shelter, my voice somehow deep and dry from the existential heaviness of not obtaining an art degree. Who’s askin’?

“You want to get your degree,” my adviser said firmly. “You’ve already invested so much time and money, and you just have one semester left.”

“What can I do?” I said.

“Is there anyone in your family you can borrow money from?” she said.

I imagined my seven-year-old sister holding a weekend bake sale or lemonade stand, and then imagined myself manipulating her into giving me the jar of quarters she earned. You know I’m good for it, I would say, my imaginary self in this scenario imagining an even less likely version of myself who was about to become rich from the sale of a piece of imaginary art, art that no imaginary version of myself could picture but that I knew must exist somewhere deep within me. I imagined bringing my sister’s jar of quarters into my financial adviser’s office and emptying it onto the desk. Plenty more where that came from, I would say, unsure why I was using a threatening tone of voice.

“No,” I said. “Nobody has any money.”

“Okay.” She sighed. “Think about it over the weekend and come back in on Monday.”

I avoided my financial adviser’s office and any phone call from an unknown number after that, hoping my tuition shortage would be forgotten.

I pulled together my interdisciplinary presentation. My weavings were actually illustrations, I explained to the jury, because I used the color and composition methods that I learned in my studies in painting and applied those concepts to the weavings. Illustration is imagery shown alongside or instead of text, and it just so happened that my weavings, when paired with their descriptions, sort of formed a satirical narrative about societal pressures. I printed books that reproduced my art next to short essays I wrote about their meaning, in case the connection to writing wasn’t clear.

“You’re so irreverent,” one of the jurors said, smiling.

It turns out being an art student while struggling to pay my bills taught me a very important life lesson after all: how to bullshit.

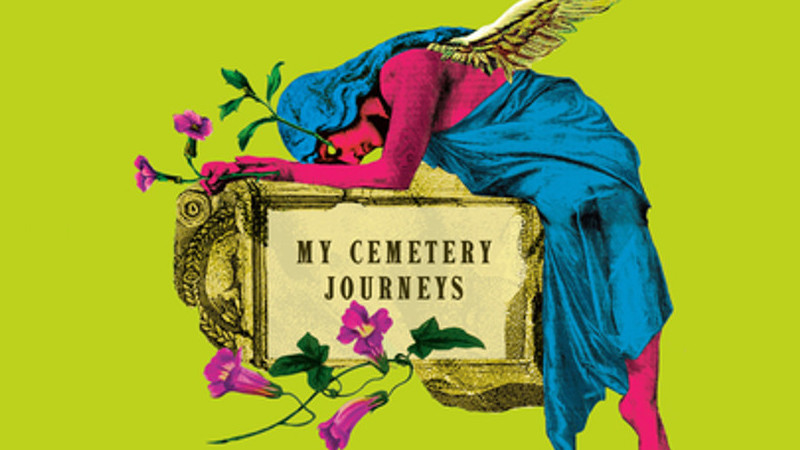

I spent my last semester finishing my requirements and taking writing classes. For my senior show, I recited a long poem I had written called “McDonald’s Is Impossible,” which I had memorized. I served McDonald’s French fries and hamburgers, which I had cut up into hors d’oeuvre–size quarters and placed elegantly on platters.

After graduation, instead of receiving a diploma, I received a bill from the school in the amount I owed. I didn’t pay it, reasoning that I would try to cough up the money if it turned out I needed a piece of paper proving I had a BFA.

I have never had a reason to see proof of my academic achievement.

Caca Dolce will lauch Wednesday, September 6th at Powerhouse Arena.

__________________________________

From Caca Dolce, by Chelsea Martin. Courtesy Soft Skull, copyright 2017 Chelsea Martin.