How Harassment at the Strip Club Prepared Me For Publishing

Michelle Gurule on Writing About Sex Work

When my essay about paying for $42,000 worth of dental work with sugar baby money first ran in HuffPost Personal, I was thrilled. Having only published in small literary magazines before, I wasn’t used to the feeling of strangers actually reading my work. The comments racked up, and my inbox filled with people’s dental horror stories. One woman told me about a root canal gone wrong, another, how she had to get dentures prematurely because periodontal disease had compromised her jaw bone. Someone offered me a cure: “The secret to healing is in your gut,” he wrote. “I know from first-hand experience.”

I was moved by these messages, because so many people said they felt less alone knowing I’d gone through this too. Not one DM mentioned my history as a sex worker, which I worried might alienate some readers. We were just a crowd of strangers bonding over our terrible teeth and the terrible dental care system of the U.S. When I skimmed the comment section, I noticed the occasional dig at my “morality,” but overall? Pleasantly teeth-oriented.

To me, writing about sex work has always been writing about class. About struggle. About cavities and electric bills—the things most of us worry about.

For the years I was a sex worker, I kept the job secret from almost everyone, terrified of judgment. That people would think I was lazy or damaged. That there had to be something wrong with me if I’d slept with someone to crawl out of debt. I’d eventually gotten over that fear in my personal life by being open with friends and family, but as a writer publishing about sex work, I hate to admit that I was still worried what the general public might think of me.

This piece had given me hope. It proved that maybe writing about sex work could actually feel connective, even relatable. To me, writing about sex work has always been writing about class. About struggle. About cavities and electric bills—the things most of us worry about. That headline invited readers to move past the click-bait and deeper into the heart of what I wanted to share: the hardships of being poor.

Then, a few weeks later, an editor at HuffPost emailed me. They wanted to republish the essay with a sex-forward title, in hopes of getting more engagement. My gut told me no. This was not the direction I wanted for the piece. I liked that the original headline had centered the cost of dental work, but I tried to think of it from a publicity perspective. Wouldn’t it be cool to get more clicks? More readers? A few dozen extra comments? And it wasn’t like the text of the essay would be changed. People had responded positively before, maybe they would again. I reluctantly agreed to the new title: “A Man Paid Me Thousands of Dollars for Sex. Most People Would Never Guess Why I Did It.”

The morning the new title ran, I woke up to direct messages from a handful of sixty-year-old men. “Lesbians are the most fun,” one wrote. Another seemed interested in hiring his own sugar baby, queried how much I had charged, and then asked bluntly if I “enjoyed the sex.”

I screenshotted his message and posted it to my Instagram story to vent about the responses I was getting. Friends reacted in shock to the audacity of the man. Who tf would send something like that? I’m so sorry you’re dealing with this. Their outrage was genuine. But to me, the messages hardly registered as anything other than: yep, this is exactly what I expected.

After years of working as a sugar baby and dancing in strip clubs, harassment—verbal, physical, casual—wasn’t shocking. This was simply how people talked to sex workers. And now that I was technically a former-sex-worker memoirist, I figured this online harassment was just part of the new job. But just because I wasn’t surprised, doesn’t mean I was disappointed by how just tweaking the title dried up the vulnerability of people sharing about their own experience, and instead I was somehow left vulnerable in a way I hadn’t really intended to be with the piece.

As the emails continued to trickle in, I felt curious about how the public comments might be different as well, so I returned to the site and read the most recent post: Personally I find sex-work/hoeing immoral, a woman wrote. If I were in her shoes I probably wouldn’t go around telling everyone about it since it does make her look low-class.

I closed the webpage, while wondering if this woman missed that the whole point of the essay was to talk about class. I was low-class. I couldn’t even afford a filling. I had been doing sex-work to change my life.

I was only nineteen the first time I danced in a strip club. After my audition, where I spun like a naive fool, unhooking my bra in Charlotte Russe chunky heels, I thought the hardest part would be learning to get comfortable being naked on stage. But that ended up surprisingly easy to adjust to. What I struggled with was realizing I had to tolerate harassment in ways that were unique to sex work.

Before knowing I was a sex worker, they’d already recognized themselves in me. There was no going back from that. That’s what I’d wanted.

Sure, I’d had rude customers when I worked in sub shops and such, but I’d never had someone try to slip their fingers inside my underwear while I worked. I’d never had men pull out their erections in lap dance cubicles, hoping I’d “accidentally” sit on them. I’d never had strangers rub their dicks against the backs of my thighs. And when I cried literal tears to managers or coworkers about it, I was told to grow up, because this was “part of the job.”

“You’ve got to tell them no while still keeping them interested,” one dancer coached me in the locker room. “Grab their hands and say something sexy, like, ‘You can look but not touch.’”

I imagine the same dancer in my house now, giving me writing advice: “You’ve got to use what you’ve got to get readers interested, and, in comparison, aren’t the emails and the comments section a better deal?”

I don’t know when, exactly, but I eventually learned to shrug off harassment at the club as background noise. Could’ve been the night I asked a man for a private dance and he said, “Come find me when you’ve lost ten pounds.” Or maybe it was the lap dance where a guy lapped his tongue in the air and begged me to sit on his face. It all started to blur into the routine. If one had a bad experience, one simply stood up and sat down with the guy at the next table over. Shitty behavior was a part of the experience. But hey, I was getting paid!

Even now, when the harassment is digital—some guy in Texas sending me an explicit message after reading my essay—my instinct is still to minimize it. Maybe it disturbs me at first, but I tell friends, my wife, my mom, It’s fine, I’m used to it. And I tell myself it’s just part of the job now, as a writer writing about sex work. And I tell myself, hey, at least I’m getting published!

When I posted that DM to Instagram, what I think I really wanted was for someone to confirm that my gut instinct had been right, and that this more sex-forward framing may have gotten more clicks, but it had made me more vulnerable while simultaneously disrupting the vulnerability of the people reading the essay. I had gained their empathy with the first title: I Needed $42k in Dental Work. I Thought I’d Take The Secret Of How I Paid For It To My Grave. The audience read of my desperation before they read anything else. They saw my shame. They saw how fucked up the U.S. medical system is. They’ve been fucked by it too. Before knowing I was a sex worker, they’d already recognized themselves in me. There was no going back from that. That’s what I’d wanted.

Writing asks me to risk exposure in order to make meaning.

But swap in the words “A Man Paid Me Thousands of Dollars for Sex,” and the context shifts entirely. Before anyone even reads the opening line, they’ve already decided who I am: not a woman crushed by medical debt, but a woman to either separate themselves from or available to sexualize. The story itself doesn’t even matter anymore. So, sure, the reach was wider, but the connection was thinner. I’m still a bit calloused to the harassment–they don’t make me hate myself or my choices–but the joy of sharing my work is a bit diminished.

Maybe I’m looking at it from the wrong point of view. Maybe I’m lucky to have learned these lessons years ago in the strip club, so that I’m able to withstand the harassment that comes my way as a writer. The truth is both jobs asked me to offer up parts of myself, and both left me exposed to other people’s projections. In the club, I learned that no matter what I did, someone would still mutter about my body, or try to take more than I was offering. On the page, no matter how carefully I build an essay, someone will still reduce me to the sex in it, or call me low-class, or try to turn my vulnerability into an example of their superiority.

But stripping also taught me how to stand firm in the face of that. It taught me that other people’s judgments say more about them than about me. It taught me that harassment is background noise, not the whole story.

So yes, the sex-forward headline left me more vulnerable than I intended (lesson learned). But it didn’t undo me. If anything, it reminded me how prepared I already was for this job. Writing asks me to risk exposure in order to make meaning. Just as I was about to close my computer, I received another DM from a strange man. I knew it might be rude, but I couldn’t help myself. I opened the message and read, “Congratulations on your journey. Your display of courage is most inspiring.” It felt like a reminder, that the trick is to keep choosing vulnerability anyway, because that’s the only way connection happens.

__________________________________

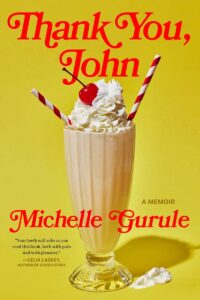

Thank You, John by Michelle Gurule is available from Unnamed Press.

Michelle Gurule

Michelle Gurule (she/her) is a writer and educator based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her creative work, which explores the complexities of sex work, class, power and Michelle’s intersectional identity as a queer, mixed-ethnicity (white / Chicana) woman, has appeared in The Offing, Joyland, StoryQuarterly, Drunk Monkeys, Homology, and Alien. In 2021, her essay, “Exit Route,” won StoryQuarterly’s Nonfiction Prize, judged by T Kira Madden. She currently teaches writing at Arizona State University as well as The University of Colorado, Boulder. She lives in New Mexico with her partner Daisy.