How Archivists Uncover the Clues to History

Isaac Fellman on Finding “Curiosity, Delight, Humor, and Desolation”

When you’re an archivist, people ask you what your favorite thing in the archives is. I often respond with “I can’t pick one of my children,” not because I think that’s true (the archives aren’t my children; they are my aging parents who say confusing things about the 70s), but because the answer is “the pube jars,” and I’m trying to think of another answer. Sometimes I do feel comfortable saying “the pube jars.” Sometimes I look into the person’s eyes and all I can think is, “You seem nice; maybe you are nice; do we have to do this intrusive thought right now?” And then I say, “the pube jars.”

The jars come from the collection of Robert Chesley (accession number #1993-06). I work at a queer historical society, and Chesley was a gay playwright. He was not, however, the collector of the shaven masses of pubic hair, which are kept in spice jars, each one labeled with a man’s first name. I know they’re not his jars because some Chesley stans came by the archives one day and did a deep dive on the topic, prompted by their awareness of Chesley’s kinks, which didn’t include this one. Their conclusion: Chesley had inherited the jars from a friend who died unexpectedly.

He kept them—why? As a memorial, I assume, and because you can’t throw such a thing away. What do you do with mementoes of someone’s sex life, mementoes that grew from the human body? It wouldn’t be right to throw them out, and it wouldn’t be right to burn or bury them. The garbage insults the dignity of a body. Burial insults the ephemerality of pleasure. All you can do is keep them, and so Chesley did, and when he died in turn, so did we.

The narrator of my novel Dead Collections, who is an archivist and also a vampire, observes that “in general what you find in archives is the absence of a body, the chalk outline of a life, crowded all around with papers and artifacts and ephemera, but with a terribly small hollowness within.” The archives are where the body is not. This is the reason the most ardent nonbeliever can feel that the archives are haunted: if a zombie is the horror of a body without a soul, a ghost is the horror of a soul without a body.

In the archives, we hold papers smeared by inky fists, and books from which small hairs drop, and photographs of people who felt sexy that day and wanted their sexiness commemorated, and we are very aware of the flesh that’s absent. Even if the donors and subjects are alive, they’ve left pieces of themselves behind in a way that reminds us that the moment is gone.

People cry in the archives. You need to leave room for tears.

Recently, I catalogued some midcentury letters from a person I thought was a campy gay man, who described working as a screenwriter, serving in the Air Force reserves, and enacting a daring plan to send flowers to Joan Crawford. He signed himself “Mother,” a common joke for gay men of this era. It was late in the process when I realized that this was, in fact, the donor’s actual mother. Her name was Margo, and her letters hold a wealth of information, valuable for researchers. They provide an example of an out gay man’s parent supporting and loving him in the 1950s. They show how women in the Air Force (presumably veterans of the Second World War) felt about ongoing careers in the service. They even speak to the queer connections a worldly woman in Hollywood might have. Margo pinged my gaydar for a reason. No doubt she was picking up her speech patterns from people around her, as writers do.

But her letters are surrounded by absences. Her son Ron kept them with him, in the Victorian house he lovingly decorated with his boyfriend Stan (their collection contains enormous bills for antique furniture, and the living room featured a pipe organ built into the wall). But Ron died in the 80s, and Stan grew old alone and couldn’t maintain the house. By the time he died, almost nothing inside could be saved from the mold. What was left was one box of letters and ephemera, and the house itself, which has been flipped, gutted, and painted a uniform white. No trace of the pipe organ remains. Where did Margo, Stan, and Ron go? I don’t believe in an afterlife, but I do believe in archives; insofar as they went anywhere, they came here. Only they came here incomplete, and what’s left of them is like a sentence with the vowels missing.

Archival emotions are big. There’s curiosity, delight, humor, desolation. People mostly come to the archives to do intellectual work—to find out how people lived in the past, how they described their days and how they spent them—but they often end up doing emotional work as well. People cry in the archives. You need to leave room for tears. You need to leave room for boredom, too; for every Ron and Margo, there’s a collection that’s composed entirely of financial records, or clippings on something arcane. Sometimes those collections fulfill a researcher’s wildest fantasies. They’re still dull to explore, and that dullness is an archival experience as well.

The strongest archival emotion, though, is awareness of paradox. Of all the collections I’ve worked with recently, the one with the most striking paradoxes was that of Felicia “Flames” Elizondo. Elizondo was a trans woman, a professional drag queen, and a fixture of San Francisco’s queer activist community for decades. In the late sixties, she used to hang out at Compton’s Cafeteria, site of the riot that ignited local trans resistance against police brutality. When she died last May after many years living with HIV, Elizondo’s family donated her collection to the archives—but when it arrived, we found that she was missing.

Her clothes and costumes were there. We found her trans flag cape, her bedazzled denim jacket, her home-sewn cloak with its dozens of polyester ruffles. But when it came to written evidence of her life, all we found was papers from Elizondo’s friend, Vicki Marlane, which Elizondo had kept safe since Marlane’s death in 2011. The two were close friends, and Elizondo had even helped to name a local street, Vicki Mar Lane, after her. In caring for the memory of another iconic trans woman and drag performer, Elizondo had ignored her own.

Archives are repositories of memory, of course, but what that platitude overlooks is that they have all the failings of memory.

Once again, we had the clothes, but not the person; the outline, but not the interior. It’s not quite accurate to say that the clothes don’t teach us about the person, or else the archives wouldn’t collect them, but clothes can’t capture our thoughts the way that papers can. The paradox of Elizondo’s papers, though, was that by her absence, she did teach us about herself. Her devotion to Marlane’s memory tells a story of solidarity and friendship, of humility and care. It tells the kind of story papers can’t tell, because it is an action and not a word.

Archives are repositories of memory, of course, but what that platitude overlooks is that they have all the failings of memory: gaps, self-serving myths, and a tendency to arrive at their own speed, not the speed we want. These failings only make the archives more human, more in need of our care. I want people to approach the past, not only with intellectual curiosity and with passionate critical thought, but also with an openness to feeling. The work of denying our feelings is hard, and it’s alienating, and it’s not worth it. I want the work of history to be the opposite of that; I want the work of history to use our whole minds.

__________________________________

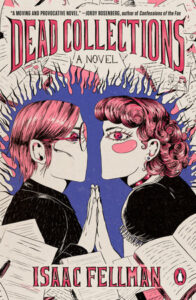

Dead Collections by Isaac Fellman is available via Penguin Books.

Isaac Fellman

Isaac Fellman is the author of The Breath of the Sun (published under his pre-transition first name), which won the 2019 Lambda Literary Award for LGBT Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror. He is an archivist at a queer historical society in San Francisco.