This story originally appeared as “Raising the House” in Great River Review.

In her adulthood strangers asked, “Where’d you get your accent?” They guessed England, they guessed Sweden, they guessed the South. She’d shrug, even as an adult. It pleased her to have her words come out of her mouth with no fixed address, as if the English she spoke was soft and malleable.

*

In that house where she grew there were seven rooms, but once she dreamed of an eighth. Behind the washing machine and dusty finches’ cage, she found a secret door that opened to a nineteenth-century library. There were bookcases covering the walls, a red oriental carpet, a long rectangular window at the ceiling. In her dream she felt a sweet despair: what beautiful things her parents kept from her! She understood then that they were just a little cruel, to hide the best room in the house from their children.

*

Their bedroom was on the second floor. Dark, walled in pine boards with knots like faces. As a child, Lynn used to nap in their bed and feel watched. She didn’t like going to sleep when it was light and waking up in the dark. She felt that something of hers had been stolen. Beneath the floor she heard their voices—the voices of people who’d had afternoons. She hated them because they left her alone with her sleep, which was like a soft animal that crawled onto her chest and slowly suffocated her.

*

Her sister said they should carry their dolls outside and set them on the driveway for someone to find, someone better.The dolls had faces that had been chewed on by dogs. “Look at them,” Henna said, grim and self-righteous. But they weren’t ruined! The dogs had left them slippery with drool, but they still had all their parts. When you pressed the button on her arm, Isabella still opened her mouth and cried.

Still, the tiny pockmarks were like a disease of the skin she could neither cure nor imagine away.

Henna lined them up on the asphalt, tiny arms open and waiting. The sign under the mailbox said SAVE US.

Lynn stayed in the house and watched through a crack in the curtains. The babies looked like garbage. They looked like war. A boy came by on his bike, eyed them, and asked, “Do you have any baseball cards?”

Henna said, “No.” She was drawing hearts on her shoe with a pen.

The boy said, “Do you have anything good?”

*

Her parents’ room was at the top of a narrow staircase, the only room on the second floor. It had steeply sloped ceilings, a worn gray carpet, a door that locked. When Henna turned thirteen, her parents moved out, dragged their dismantled bedframe to the unfinished basement. Henna set her collection of glass cats on their windowsill. She covered the pine-knot faces in the wall with her posters of Nadia Comaneci.

In the other bedroom, the one on the first floor of the house, Lynn’s brother moved out of his crib and into the bunk below her. He did not sleep soundly, as Henna had, but turned and turned under his dreams. It was like bobbing in a rickety boat, the way the wooden bunk bed creaked and shifted beneath her. Lynn said, “Saul, Saul?” hanging her head down to peek at him. The mice turned their wheels in their glass cage.

*

This is the story her father told her: the house was given in debt or payment to her grandfather’s father. It belonged first to a farmer, though no one knew what kind, and they set it on wheels and drove it with flashing lights to the new edge of the city. As a child, Lynn thought often of the farmer who gave it up, who stood in a field somewhere and watched it go like a parade.

They dug a foundation from the hillside and set it down by the pond. The house was clapboard and square, brown-shuttered. In the beginning, it was like a body without limbs, just the most important rooms, the ones you need to stay alive. Then her young grandfather added the upstairs bedroom and garage, covered the back bathroom in pale blue tiles, screened in the open porch. He used the parts of other houses no one wanted anymore. Her grandfather had worked in demolition before auto repair in the years after the war, and he’d pilfered other people’s old doors, their cracked windowpanes and tiles, their long, skittery moldings. When the mice got loose, they lived for a while in the heating ducts. You could hear them running past, their claws ticking in the metal pipes, their bodies shushing against the walls. Then they settled under the refrigerator and made babies. Lynn set her ear on the linoleum and shined a flashlight into the narrow crack. They blinked their black, identical eyes. Their babies looked like pale pink stools.

She didn’t know how the mice got out of their cage, but she didn’t tell her parents. When her mother put Saul to bed—a purse on her shoulder, a sock in her hand—Lynn made a show of filling the blue plastic bowl with seed. She declared, “Midget and Dill look sleepy!” burrowing her finger in some wood shavings.

After her mother left for her night shift at the hospital, Lynn lifted the bowl of food from the cage and emptied it in the toilet. The black seeds floated on the green surface. She flushed and flushed.

“Poopy, poopy, poopy!” Saul said when she got back. She hissed at him, “Baby!”

During the summer, her par *carried the TV out to the porchents where it was cooler. There were no curtains or shades, just a crimped rusty screen from knee to ceiling. You could hear the TV from down the street, and at night a blue glow lit up the front yard. Sometimes Lynn stopped her bike outside at dusk and listened. There was the sound of the cottonwoods against the roof, like a flock of nervous birds, and the dogs at the back door whining. There was a gunshot on television. There was the sound of her mother on the porch, saying, “Just a carpet for the hallway. Just a machine with a button you can push.”

Her father said, “Just a dishwasher is more complicated than that.”

The TV said, “The polar bear is nearly extinct.”

*

After her parents moved to the basement, her mother started making plans for the house. She wanted to add a new wing to the back, with a sliding glass door that opened onto a deck. She wanted a sink that didn’t leak into a bucket. She got a beautiful, determined look on her face and walked from room to room, squinting at walls. She made the bathroom into a closet; she made the bedroom into a two-car garage. She asked Henna, “Would you like wallpaper for your new room? Do you want carpet or wood?” Henna was suspicious. She worried that her room would no longer be the nicest in the house. She said, mimicking their father,

“What an asinine suggestion! There’s no money for that.”

Lynn saw her mother blink and pull a lock of wet hair from Henna’s mouth. She used two pinched fingers, as if extracting something from a puddle. “Yuck, Henna,” she said. “Yuck.”

At dinner, Henna sat next to their father, who had flecks of grease on his hands from his auto body shop. He hit the ketchup bottle with one swift blow against his palm. “Pass the sauerkraut,” he said.

Their mother kept it. She described the new kitchen she wanted: the wall she wanted to knock down, the new white linoleum. She made it sound like a country she planned to visit, somewhere far away and scenic, a place they might all go to together. The Kitchen.

Their father pulled some leaky ketchup from the bottle with a knife. “Don’t be asinine, Linda.”

She looked at him. He said, “Well, really.”

Their mother was quiet. She had a mechanical anger, Lynn knew, like a wind-up gear. She needed a second to turn the screw and let it release. Then their mother tipped a bowl over and emptied all the sauerkraut onto her plate. It covered everything—her peas, her hotdog, her tiny wad of gum. It slid onto the table.

“That wasn’t necessary,” their father said.

Their mother said, “Of course not.”

Lynn described the library dream once to her lover. She remembered everything: the shiny wooden shelves, the walls of weathered books, the dense smell of old carpet. It was so clear it seemed possible to go back, to fill the car with gas and drive through the night, to find the key under the birdbath by the door, climb down the damp stairs, and open the tiny, hidden door behind the hanging laundry. She knew how the doorknob would feel (a little sticky, cool) and the ten even steps from one side of the room to the other. At the same time, she knew it was impossible to go to the library just like it was impossible to return to that house, which had been so neatly crushed by a single cottonwood. The trunk of the tree came down through the roof one night, splintering rafters and shingles and walls, then lay quietly in the upstairs room like a new piece of furniture.

*

When their father bought the couch at Sears, he wrapped it in tarps and drove it home in the bed of his pick-up. Bound in clear plastic, it looked like the giant larva of a huge insect, something waiting to hatch. Their mother stood in the driveway, saying, “What is that? What is that?” her hands on her hips.

Their father smiled and blushed. He sliced through the twine with a utility knife and slit open the plastic. The pale upholstery was the color of skin after a burn, perfect and impossibly pink. He helped their mother into the bed of the truck, and she looked like a prom queen up there, waving shyly at them all, perched primly on her new pink couch. Lynn could tell she didn’t want to look too pleased. “It won’t match, Alec,” she complained. “It’s too much.” Then she leaned back and shrieked, “It’s like being swallowed!”

*

Their neighbors, the Kenyons, had twin girls who played the violin.

On the street, you could hear them practicing—tight little scales, lively arpeggios like stones skipped in water. They also had a Siamese cat they dressed in doll clothes, who wandered in calico on their roof. The Kenyon girls were several years younger than Lynn, but sometimes they saw her in a tree somewhere and climbed up after. They were polite and affectionate. They slapped mosquitoes on Lynn’s bare legs. From time to time, they kissed each other on the lips and wanted to kiss Lynn too, but Lynn climbed out of reach.

When Mrs. Kenyon came out of the house, Lynn knew there’d be trouble. Mrs. Kenyon yelled, “Alia! Megan!” pulling hoses around on the grass, pointing sprinklers at beds of hostas. Lynn scrambled up as high as she could get, but the Kenyon girls cried, “Mom! Mom!” dangling precariously. They wanted Mrs. Kenyon to be afraid for them, which she was. She ran to the broad trunk of the tree and put her hands in the air, as if planning to catch them. She yelped, “Careful!” grabbing at their ankles, which made it difficult for the girls to climb down.

On the ground, they giggled and sobbed. “We’re alright! We’re alright!” they said, as if surprised by this outcome.

Mrs. Kenyon glared up into the branches. “Lynn!” Lynn slid slowly down, barely moving her body.

Mrs. Kenyon put her hands on her hips. “Lynn, you’re the older one, take some responsibility. ”She turned to the girls. “For the rest of the day, you can play inside.”

The Kenyon girls—red-eyed with tears, with excitement—said, “Can we go to Lynn’s house, then?”

Mrs. Kenyon and Lynn said, “No!”

But Lynn didn’t like how Mrs. Kenyon walked the girls back across the street, one in each hand, like luggage.

She revised to maybe, calling after them across the street: “Maybe tomorrow! Maybe the day after that!”

*

Each night that summer, Lynn filled the plastic bowl in the empty glass cage. She spun the metal wheel with her hand and ruffled the shavings. In the kitchen, she aimed a flashlight under the refrigerator and watched the mice clean their whiskers with their twiggy hands. The babies fumbled for their parents’ flanks, doddering and unsteady on their feet, holding their tails stiff for balance.

Once when she clicked the light into the humming darkness, they were gone.

She put her face against the sticky linoleum, her cheek, her ear. The mice were gone, but not their babies. They were white and dry as bits of powdered donuts, except for the red on the places where they were chewed in half.

She clicked the light off and on again. Off and on.

In her room, Lynn filled the food in the cage, checked the water, and smoothed down the shavings. She touched an old pellet of poop, hard as the tiniest of glass beads. She said to Saul, who was watching her from his bed, “Do you want to play with the mice, Sauly?”

He sat up, excited, shoving the covers off. “Yes!”

She made a cup with her hands and crawled into bed with him. “Careful,” she warned. “You have to be very, very careful with tiny animals.”

He held out his hands, rigid with pleasure, waiting for Dill to walk in.

*

The morning their mother didn’t come home from her night shift and their father left early for work, they stayed in bed. At first they lay beneath the covers, thrilled by their unexpected fortune. When the sun grew hot on the blankets, they got up for snacks, for buttered sugar on bread, then climbed back under the sheets and waited. They waited for someone to come by—the bus driver, the neighbors—and worry on their behalf. It felt like a holiday or disaster to be in bed like this, a very special occasion.

But no one came, and Henna grew lonely in her upstairs room, so she coaxed Lynn and Saul out to the porch. The TV was there, leftover from the humid summer days, so they sat in frayed wicker chairs and watched cartoons. The day was bright and hot, though it was already September. The kindergartners were riding home on buses. In another part of the city, Lynn’s class was learning cursive and drawing Mars in glossy books. In another house down the street, someone was cleaning the welcome mat with a vacuum.

The postman with his blue satchel came up the driveway. He waved at them cheerfully through the screen. “Hey, there!” he called, but then his expression grew puzzled. “You kids off from school?”

Henna shot up from her chair, nodding, then shaking her head. “Well, actually, we’re sick today!” She opened the door a tiny crack to cough and take the mail. Her face was bright red.

After the postman left, Henna turned off the TV and rushed them inside. Lynn could see certain realities were beginning to dawn on her. “This is my first tardy!” she said. “My first one all year!”

She looked at Lynn and Saul like it was all their idea.

They went back to bed. Saul didn’t want to, but Henna held him down and explained, “We’re sick today!”She was worried now about what her new middle school teachers would say. She wanted an excused absence.

Lynn coaxed him. “Bang, bang,” she said, and Saul lay back on the pillows because he liked games where he got shot. Henna decided to sleep in Lynn’s bed, where she curled up in a ball and coughed. “Stop it,” Lynn whispered, but Henna countered, “I’m sick today, Lynn!”

Lynn’s sleep was white and despairing. She kept thinking she was crawling out of bed, putting on her shoes, going outside, but then she’d wake and find her head heavy on the pillow. Henna was chewing a lock of her own hair, pulling it from her mouth and making a dark spoke that pointed straight at the ceiling. Beneath them, Saul was either gone or so still he was hardly breathing. Lynn closed her eyes and let sleep drop its soft animal body— crushing her, turning her over—then she opened her eyes again. That’s when she saw their mother in the doorway.

Their mother was staring at them, confused.

“What’s this?” She rushed in and lifted Saul in her arms, shaking him. “Did your father leave you like this?” Her fly was open. Her shoes were off.

She grabbed Lynn’s ankle and almost pulled her from bed. She kneeled on the floor and rifled through dirty clothes, lifting and discarding garments. “What were you thinking?” she accused them.

She turned on Henna last and said, “You’re not even dressed!”

Henna backed into the corner of Lynn’s bed, her eyes red, her knees pulled up inside of her T-shirt.

“We’re sick,” Lynn pleaded. She wanted her mother to feel how hot she was; she wanted to reach for her hand and put it on her head. She got up on her knees and begged her mother, “We’re in bed because we’re sick.”

*

Every fall, her father opened a door in the ceiling of Henna’s room and disappeared into the attic. He set traps for the wild animals that wintered there—the squirrels, the raccoons, the mice. The traps were simple coils of wire, and they looked like something friendly you should talk into, primitive phones, the doorbells you can build from kits.

The fall after the mice escaped, Lynn asked to follow him up the ladder to lay the traps. She’d read books about attics and imagined giant rafters, shuttered windows, furniture draped in white sheets. She wanted to see the sort of room that was on top of everything. But this attic felt like a hole in the ground. Her father said, “Don’t stand up. Scoot on your butt. Distribute your weight evenly.”

When her father clicked on the flashlight, she saw that the roof was just inches from their heads, pink insulation sagging. Lynn reached up and unwound her hair from a nail.

“This house was built in 1901 by a pioneer.”

Lynn sneezed. “I know that.” She’d heard the story and wanted something else, some other tunnel to the past, another line of history. The tiny attic made her dizzy.

Her father handed Lynn the flashlight to hold as he pried open the wire mouth of a trap. Then he set down a Girl Scout cookie, frozen since spring, when Lynn had knocked on other people’s doors and stood in their warm hallways.

The cookie glinted white with frost.

He said, “This will take those little buggers out.” But he seemed sorry about it, as if it were an unpleasant requirement of fatherhood, the ritual kill. He secured the cookie on the platform.

Lynn asked, “Where does it get them?”

He hesitated. “By their necks.” And she could tell by his voice he was pleased with her question, pleased to see she understood that being alive in the world meant a series of such indignities, of killing and being killed.

He scooted backward into her. “You want to come with me to pick up the animals?”

Lynn thought of the black, blinking eyes of the mice, the split open slugs of their babies. She didn’t want to come back for them. She said, “Yes.”

Their father and Saul were home when the tree came down, waiting out the storm in the basement. Everyone else was away that night: their mother working at the hospital, Henna at college, Lynn in a car with a boy she loved painfully, who sang long, fretting songs for her and recorded them on cassette tapes. Lynn watched the storm from a hilltop across town, the boy’s off-key voice coming through the speakers, the boy’s hand on her leg. She loved this boy but was a little bored. She’d heard this song before. The boy’s cassette voice sang, “War, children, it’s just a shot a way. Juuust a shot away.”

Saul said the tree shook the whole house. It made the washing machine shudder next to them in the basement and knocked the finches’ cage down to the floor. The birds swooped out the open cage door and up the stairway. Their father followed, and then Saul, with the cordless phone clenched in his hand, tapping out 9-1-1, though of course the line was dead.

The dogs stayed trembling in the basement.

Upstairs, wet plaster from the kitchen ceiling lay in a scattered dark mound on the linoleum. Up one more flight of stairs, in Henna’s room, it was raining. First they saw a few wet, green branches heaped against the dresser, and then the long, white trunk, nestled deeply in the collapsed rafters. Saul said later it looked like an endangered animal, something you’re not supposed to be able to see in your lifetime, huge and very, very tired.

Saul was a bookish teenager, the sort with very few friends.

*

One year, the Kenyons asked Lynn to cat-sit for them when they went to Disney World. They showed her how to empty the kitty litter and carry the cat’s bowl to the kitchen, where the water was cleaned by a special filter in the tap. They gave her the code for the garage, and she walked over there before her brother and sister woke up, letting the garage door rumble closed behind her. She was very good at this job, responsible and conscientious. She did things she wasn’t asked: she watered the violets and emptied the wastepaper basket. She watched movies in their basement—black-and-white classics with nervous ladies—the cat stepping daintily over her stretched-out legs. She ate chewy Cheetos from their cabinets. She lay down on the girls’ beds, which were in separate but identical yellow rooms, and enjoyed their separate but identical pillows. She took a shower. She used their soap and towels. She put on the girls’ socks, too small for her, but clean and tight as slippers. She went into their parents’ room and read the notes in their coat pockets: Home at 6. Meet you at King Tut. Get Milk.

*

When her mother stooped next to the cage and asked, “Where are the mice?” Lynn was calm, almost surprised that she’d asked. By then the mice had been gone for several weeks, the babies born, killed, and rotted, their stench ripe for a few days but long since faded.

She said, “What do you mean, where?”

Her mother tapped the empty cage with a painted nail. “I mean, where are they?”

Lynn was on her bed, smoothing the fur of a bear flat then rough. “They must be there,” she said.

“They’re not.” Her mother pried the lid open. Inside, the shavings were crisp and blond as the dyed hair of old ladies.

Lynn asked, “Did they get out?” touching the bear’s blue plastic eye.

“Oh, no.” Her mother straightened up and looked around at the

floor. She nudged a pair of jeans with her toe.

Lynn said, trying to sound worried and sad, “Do you think Saul tried to hold them?”

“Oh, no.”

“Oh, no,” Lynn said.

*

She called her parents one night when she was living in a city with mountains and a cereal factory. That was when she could smell burnt popcorn all day, a cheap movie-theater scent in every room and park and office. She called her parents late at night, balancing her address book on her lap because she had never memorized the number for their new apartment. The phone rang and rang. They’d lived in that apartment for more than a decade. The ringing seemed to go on and on, and she thought, It’s happened, they’re gone, and once she thought it, she wished it true, her grief over it was so good, so complete, so utterly wasting. There was no other way to feel about them in the world. There was grief or nothing.

Of course her mother answered the phone, breathless, and said, “God, Lynn, you must be desperate!”Then she wasn’t anymore.

*

She had dreams about the fallen cottonwood, and dreams about the library under the house, and sometimes dreams about her mother. In the dreams, her mother had hands that curled up slightly and a button on her chest that you could press to make her talk. She said “Save Me,” but Lynn would not.

One year her mother asked her to go for a walk after Thanksgiving dinner. There were still a few hours before Lynn’s plane left the city, so they bundled up and set out. By then, her mother was a little stooped, shaky from a recent hip operation. They walked slowly past the apartment complexes and condos, past the new subdivisions with their shoveled sidewalks, past the old highway to the quarry on the other side of town. There, sumac rattled brittle leaves. The wind swept up the snow in shrouds.

“It’s pretty here,” Lynn said, feeling an unfamiliar lightness. She remembered riding her bike through these quarry dunes as a child. She remembered falling off and carrying a gravelly wound home on her arm. For a second, she felt a sentimental protectiveness—for the injured girl pushing her bike, for her mother, hobbling enthusiastically through the snow, for the past, which was so pitiful and distant.

“Look out,” Lynn warned. Her mother was climbing up a drift of snow, and Lynn took her mittened hand in her own, steadying her.

She said, almost tenderly, “Mom, Mom.” The sun had slid behind the dunes. “Should we go back?”

“You were always the worrier, Lynn.” “It’s just, it’s getting late.”

“You were always my favorite, though.”

Lynn turned. This was something their mother said to all of them at one time or another. Still, it worked like a blow to the chest. In the last light, Lynn could just make out her mother’s face: her bright red nose, her slightly parted lips. For a second, she despised the needy way her mother smiled, the way her beanie was slipping to the very top of her head and would soon fall off. She wanted something from Lynn, of course, but Lynn walked on, carefully saying nothing.

They continued to the edge of the old highway, which was difficult to distinguish because it hadn’t been plowed. A few ragged tire-lines marked it.

“I have an idea.” Lynn felt her mother’s mitten on her arm, the heavy weight of that woolen paw. “Let’s go by the old house on the way back.”

Lynn grew impatient. “No, Mom.” “Why shouldn’t we?”

“You hated that place.”

“That’s where you grew up!” Her mother sounded offended. “You called it a dump.”

Her mother winced. “Don’t you even want to see what happened to it?”

She did not. In Lynn’s mind, it had simply collapsed. The house was still waiting for demolition. It hadn’t occurred to her until now to consider other possibilities: the lot paved into a parking lot for the nearby dentist, or seeded over with those skeletal, malignant cottonwoods, or—worst of all—the house still there, as always.

Remodeled, fixed-up, the same clapboard box repainted and enlarged. It unnerved her to think of lights on in the windows, people mutely speaking inside, an empty car running in the driveway.

Lynn noticed her mother was staring at her.

“Were you so unhappy, Lynn?” Now her mother was impatient, moving on ahead.

“No, Mom.”

“Did all those Girl Scout meetings and pets and toys, did they, what, scar you somehow?” Her mother glanced back once, pulling her beanie down over her ears like a lost little kid. Her filmy gray eyes were huge. “Why do you always act like you were a victim of us? Oh, honey. I love you, I do, but I refuse to say poor girl.”

*

A few weeks after Thanksgiving, Lynn’s brother called. They talked for a while about collies and taxes, about a bus strike in a distant city. It often surprised Lynn that this restrained, educated man was once her little brother. It embarrassed her to think how he was once almost a part of her body: the brother part, that went everywhere she did.

Just as Lynn was preparing to say goodbye, Saul added, bashfully, “Mom’s upset. She thinks you’re keeping something from us.” Us. She wanted to punish him for working against her. She wanted to remind him that he was hers, the brother part of her body. But when she opened her mouth, a sound like a sob came out.

“Lynn?”

“Fuck off, Saul, for once!” she said. Then, quickly, “No, no. I’m sorry. Listen.” She wanted to offer him something, to be forgiven. She said, abruptly, “I killed the mice.”

“What?”

“Midget and Dill.” The names were absurd. She started to laugh. “I thought I did that.” She could hear in his voice the sound of a person stopping in his tracks and trying to get oriented. “I took them out of the cage and let them go when I was a little kid.”

“That’s what Mom told you!” It felt right to accuse her. “They got out on their own and lived under the refrigerator. They had babies and ate them.”

“That’s sick. I still dream about them all the time. I know how they felt when I lifted them out, how they struggled, and I squeezed their necks. I remember everything.”

He sounded so bleak, so remorseful.

“You were just a kid, Sauly!”she reassured him. “You didn’t know any better!”

There was a pause. “But you just said I didn’t do anything.” Lynn put one palm against her mouth to keep from arguing.

She lifted it up to say, “Yeah, well—” then put it back, very neatly. She felt confused, now, and distrustful of Saul, who talked secretly to their mother after Lynn was gone, who was the true favorite, the beloved son, who believed everything he was told.

*

When her mother died, Lynn was as in bed with a man who refused to make love to her unless she begged for it, unless she put her hands on his dick and said please, please. Her sister made the call, and when Lynn’s lover answered the phone, he said, “Wait a second—” He fumbled over Lynn, found his glasses on the nightstand, and then said into the phone, “Alrighty, then.” Lynn could hear her sister’s voice through the phone, her impatience with this man she did not know. She could hear in her sister’s voice how much she resented Lynn this performance of politeness with a stranger. Lynn took the receiver and spoke to her sister for less than two minutes. She heard her lover flush the toilet in the bathroom. When she hung up the phone, there was a brief, blind moment when his face fled her mind. She couldn’t feel the bed beneath her or her hands squeezing her thighs. She couldn’t fathom who would come out of the bathroom when the door opened up. Then she remembered and he came out.

*

“The library only had books with creamy leather covers,” she said. “There was a wingback chair in the corner with worn arms and a single brass lamp. And there were these old portraits of people on the walls, total strangers. Gilded frames, frowning faces. Three whole walls were covered floor to ceiling with books. Their spines creaked when you opened them up, and the words were in written in this tiny, elegant font. Like every book was a Bible. But listen. If you pulled a book from any shelf all the other books shifted to fill in the space it had left. There were never any gaps.”

“My room was the conservatory.” Henna was sipping red wine from a glass. They were in the basement of their childhood church, sitting at a long folding table. It had been afternoon not long ago, but now it was night. All the coifed cousins and hunched uncles had already left to scrape ice from their windshields and beat rushhour traffic. Lynn and Henna and Saul were waiting for their father to finish signing papers in the church office.

“Your room?” Lynn asked, confused. Her own wine glass was empty.

“You’re talking about that game we used to play, right? When, like, we were all crammed together in the backseat, stuck in traffic. Tearing into each other.”

“I don’t remember any game.”

“‘You get one room to yourself,’ Mom would say. ‘And no one else can ever come inside. What room is it you want?’ She did it to stop us from squabbling. I said conservatory because I liked that room in Clue. Mom said kitchen, of course, and Saul—? Sauly, you weren’t born yet, were you?” Henna looked over at Saul, who was sitting blank-faced on a column of folding chairs he had just stacked. His beard was damp. His long white fingers were splayed out over his knees.

Lynn shook her head. “That’s not—” “I was born,” Saul said.

Henna was giggling, tipsy. “Lynn always said library, library, library.”

“I was born!” Saul said, more loudly.

“It was a game?” It was a dream. Lynn felt uneasy now. And worried that Saul might be crying silently to himself, and irritated with Henna for getting drunk. Why couldn’t they ever pat each other’s hands or tell stupid jokes, offer some measure of consolation? It unsettled her that she couldn’t call up a single image of them all sitting together in the backseat of some car, stuck in traffic. She tried but couldn’t remember her shoulders touching Henna’s and Saul’s, couldn’t remember the drumbeat bass from another car’s radio, couldn’t recall Saul’s sticky little arm elbowing hers, or Henna kicking her legs out across Lynn’s lap. She couldn’t remember it and then, like waking from a dream itself, she did— of course, she did—their mother whipping around from the front seat, her face tired but trying as she suggested her game, and everyone groaning when their father said bed. Shelter, the game was called. Their mother’s game.

“Saul was born,” Lynn whispered. “I was, I was,” he said.

She lurched across the table to touch his arm as he sobbed.

He shirked away from her reaching hand. Even so, his bearded child’s face was so hopeful, and so stricken, that it seemed possible to Lynn for a brief instant that no other reality had in fact ever fully existed for any of them, that there had only ever been that old car on the highway with all of them inside, each locked in their chosen rooms, and she wondered in anguish and awe how many times she would forget and have to remember this again.

__________________________________

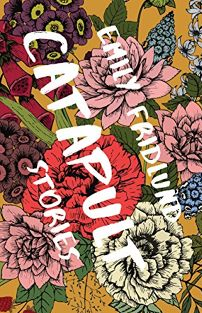

From CATAPULT. Used with permission of Sarabande Books. Copyright © 2017 by Emily Fridlund.